Jiri Diamant was deported to the Terezin ghetto by transport Ad from Brno on 23rd March 1942 together with his parents and a younger brother. He stayed at the boys’ Heim L 417 for many months, then he and his family were sent to the family camp in Birkenau in December 1943 (for details see Newsletter 1/2004). In early July 1944 there was made a decision about a selection in the camp, which in fact meant liquidation of the family camp. Only 3,500 of the present men and women were then recognized as able-to-work and left that place of death. The rest of the prisoners – old, ill and mothers with children – were to face gas chambers.

Fates of Birkenau Boys

Among them were dozens of boys around 14 and 15 years of age. Then one of them found the courage and asked the camp “doctor” Mengele to chose individuals able to work also among them. Surprisingly, he agreed and had a crowd of teen prisoners march again. Out of them, he compiled a group of about 90 boys which he then moved to the nearby men’s camp, marked B II d. All other prisoners of the family camp were to die. As obvious, the International Red Cross was unlikely to visit local sites, therefore the existence of the family camp was not necessary.

The boys were placed in the men’s camp in Block 13, known as a criminal block. The prisoners there – Poles, Germans, Russians – were under a tightened regime and got harder work. Czech boys drew attention there, however, the block supervisor did not limit their activities much; they played football or sang together Czech songs. From the Sonderkommando (Special Commando), who lived in the neighbouring block, they sometimes got extra bread and especially information about crematoria. So they learned about the fate of their relatives who had not survived the selection in the family camp. Their days were mostly filled up with work – they helped in the kitchen, brought from outside things needed to repair roads or heat houses. Some of them even worked outside the camp.

After a few weeks a selected group of “able” boys was sent to work in the Reich. Post-war statistics show that only about half of the Birkenau boys was lucky and lived to see the liberation. Over 40 of them came back home, mostly as orphans.

These boys who went through the Auschwitz hell are called “Birkenau Boys”.

(According to the survivors of Birkenau Boys: Toman Brod, Jiri Diamant and John Freund.)

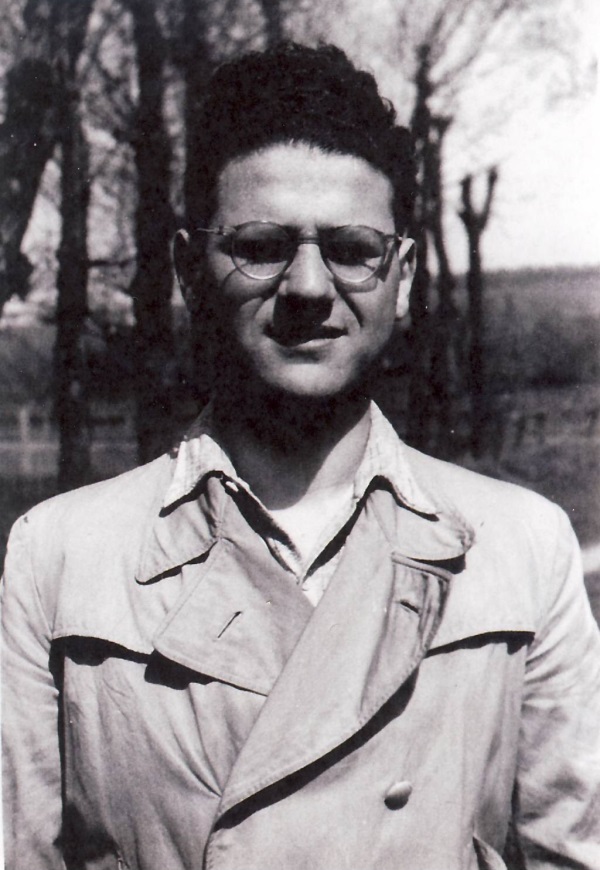

Jiri Diamant was one of those who got among the “Birkenau Boys”. He left Birkenau in a able-to-work group and was liberated in Buchenwald. He survived as the only one of his family.

When Jiri returned home after the liberation, he studied psychology and philosophy at the Faculty of Arts of the Masaryk University in Brno, and later also medical college at the Charles University in Prague. He took the carrier of a teacher and researcher. Since 1968 he has been living with his family in the Netherlands. He worked in his branch until late retirement. His lectures could also be heard at universities in Brno, Olomouc and Prague after the Velvet Revolution in 1989.

(Great success was his lecture with the title World after Holocaust at the I9th Popular Scientific Symposium for the Czechs and Slovaks living in the Netherlands in 1994, printed in the Terezin paper No. 24 in 1996. No. 23 introduced Diamant’s Notes on the Psychology of Life in the Terezin Ghetto.)

Chl.

Postscript

Family roots of Jiri Diamant are in Uhersky Brod in Moravia. As a boy he used to go there on holidays to both his grandparents the Diamants and the Löwys. Both families had decent memorials built for their dead at the local Jewish cemetery. When J. Diamant then arrived in the country first time after his emigration in 1968 and visited the graves of his ancestors, he remained shaken by the overall dismal state of the cemetery. Even more he got dismayed by the fact that both marble headstones from the graves of his former family had disappeared.

Poem about the Jewish cemetery is an elegy of the only family member who survived the Jewish holocaust during the Second World War.

Content of the poem:

Headstones at the Uhersky Brod cemetery recall that local Jewish soldiers died in the First World War for the Austria-Hungarian emperor. During the Second World War the local Jewish community was scattered, the idyll of Masaryk Republic was trampled by the Nazi invasion. After the war, some returned and lived in Brod in harmony with the others. The gravestones, however, the memorials of old times, fall into disrepair and nobody cares about them.