The first wave of transports with Jews from Slovakia took place from March through October 1942. At that time, the public had already heard rumours to the effect that the Jews were being sent to their deaths is gas chambers rather than – unlike what the propaganda said – to work camps. 57 transports were sent out. 38 of them with approximately 38 thousand people were headed for the Lublin area, the remaining 19 with some 19 thousand people were headed for Auschwitz.

M. Klein with his daughter Magdaléna – transported from the Sereď camp to the Terezin Ghetto in March 1945

Mrs Zuzana Veselá, born Gescheidtová, one of those deported to Terezín from Sereď, Slovakia recalls the time: “Originally, we were preparing for a transport to Auschwitz as soon as in June 1942, but Šaňo Mach, the Slovak Interior Minister, who was responsible for the Jewish question in Slovakia, stood up for us, paid for us and we (the whole family) were removed from an already sealed rail wagon and we were allowed to walk back home…”

Following this wave of deportations, some 20,000 Jewish people were left in Slovakia. Many of those were given exemptions (Like the father of Mrs Veselá, who according to her recollections was granted a minister’s exemption as a so-called “Economically Important Jew” and carried only a small yellow star of about 3 cm with the letters HŽ – people like that were sometimes nicknamed “Hlinka’s Jews”, as both phrases share those initial letters in Slovak), some were located in the work camps of Sereď, Nováky and Vyhne, certain percentage went into hiding. Even though the Slovak president Tiso promised Hitler’s emissary that the Jewish question would be solved by April 1944, the government did not allow any further transports until then. Tiso’s government was rather trying to concentrate the Jews in camps in Slovakia, so that they could be used as free labour force by the state and under its surveillance. The Germans however refused to accept this concept.

In the autumn of 1944, the situation in Slovakia changed. The country was invaded and occupied by German army in order to suppress the uprising and to bring the Jewish question to a close. The camp in Sereď which even briefly stopped its operation following the outbreak of the uprising was once again reactivated. By the end of September, Eichmann’s close collaborator Alois Brunner was appointed the camp’s commandant. His arrival meant new deportations. The Germans continued to put pressure on the Slovak government. At the beginning of October, H. Himmler visited Slovakia and commented on solving of the Jewish question. He argued that the Jews were some of the co-instigators of the uprising, an act of armed resistance against the Germans and if they weren’t concentrated in one spot, they probably would have had to face retribution from the country’s other citizens, which would have had put the internal peace at risk. His cynicism reached its peak when he claimed that the transports were basically in the best interest of the Jews themselves.

Mrs Veselá recalls: “… My father took part in the Slovak National Uprising… He was working until the very last moments before he escaped. We had a hideout prepared in the woods, but we did not get there… At the end of September, the Germans arrived at Zvolen. We left our home on the day they came…. We left for the mountains… Daddy had a gun and we also had a horse that carried our luggage. At night, daddy went walking rounds between field kitchens looking for something to eat (crackers, coffee substitute made from chicory)…” Later, they were caught and, along with some other people managed to escape, but eventually they were deported to the Sereď camp. Mrs Veselá writes about Sereď: “People lived in huge rooms with bunk beds, 3-4 families in one room, with food being brought in. The best experience there was when my mother once somehow managed to bake poppy seed and jam cake in the camp’s kitchen. Our family staid for quite a long time, about three weeks, but otherwise people were being brought in and out all the time. Then one day there was a roll, we had to line up in two lines and move towards a German guard who used a riding crop to separate us into groups of women with children, the elderly, men and young women. My mother was paired with my sister Magda, I walked with my daddy. Mother was sent to the group that had women with children, father to men and I to women. I quickly slipped into the group where my mum with my sister had been sent…. We stayed there all the way back to the barracks. We never saw daddy again.”

From October until mid November, transports with approximately 7,400 Jewish citizens left the Sereď camp for Auschwitz. From mid November until early December of the same year, there were transports to Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen and Bergen-Belsen. The last four transports from Sereď were headed to Terezín.

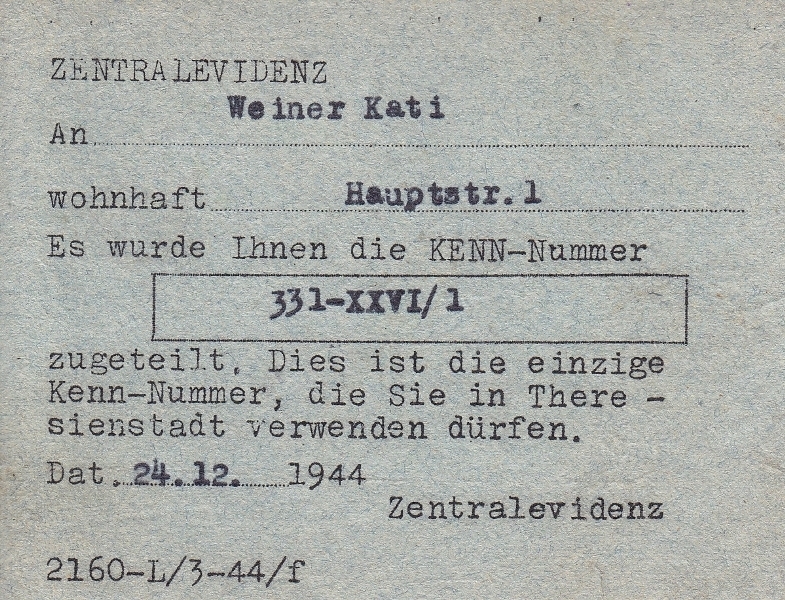

Certificate about the identification number. It was made by the Central filings in the Terezín Ghetto on December 24, 1944. Kati was transported to Terezín with the first transport from Sereď

The first of these Terezín transports was marked XXVI/1 and left Sereď on 19 December 1944. It reached Terezín on 23 December 1944. The fate of this transport is interesting. The transport most probably left Sereď with 944 people, but only 416 of them reached Terezín. Survivors say that the transport was initially headed to Auschwitz, however, the death camp facilities there were already being dismantled then and transports were actually sent out from Auschwitz in order to bring prisoners fit for physical labour to help the German economy. Thus, the train that carried Jews from Slovakia was left standing by the Auschwitz platform for a while and eventually was sent on. The witnesses say the transport was split into two parts and one of them was to end up in Terezín.

This was the transport where Mrs Veselá ended up as well: “…on evening they started loading us up in the wagons. The wagon was terribly small, it had no windows at all, they just tore off a few boards on one side so that we could get some air. We were given two buckets, one with water and one to serve as a toilet. The three of us sat down in a corner, there were blankets and mattresses on the floor. I was sitting beneath that hole in the wagon wall. We had no idea where we were headed, the wagon was sealed tight. They gave us some food for the road. I remember that as the wagon started, some lady started singing a Jewish hymn. I served as a lookout for the others, peering through the hole and striving to spy where we were passing through. When the train stopped, there were German guards watching over us in stations, we were allowed to empty the toilet bucket and new drinking water was brought in… Then, at night, the train came to a close. We found out we were standing next to a factory of some kind. I was listening to the orders that could be heard outside. We found out that a wagon has been split from the transport – it had those men and women fit for work. Only women with children arrived at Terezín.”

There were three more transports headed for Terezín, marked XXVI/2-4. They arrive on 19 January 1945, 12 March 1945 and 7 April 1945, respectively. Altogether, the four transports brought 1,447 people to Terezín, 40 of which died in the ghetto. The last transport also carried documents from the Sereď camp, those were nevertheless later burned in Terezín.

The Slovak prisoners joined became part of the life in the Terezín ghetto. The families stayed together. Capable men and women had to work, the children had to help out in farms.

Mrs Veselá remembers how, after the initial week-long quarantine period during which they did not have to work, were given food and were allowed to take a walk every now and then, they were sent to the living quarters. “We were given a room at Bahnhofstrasse, on the first floor of a house. The room was shared by the three of us and two other women with children. Our room was long and narrow, with beds lined up beside one of the walls. It had a heating stove. I remember that at night, children like me went out collecting the coal that was left lying on the ground by the rails, as it was brought into the ghetto in wagons. A lot of it was always left lying around. The beds we had were wide, for several persons, we had blankets….We also received some clothes…. I originally started working at the day care centre, the Tagesheim, where I cared for very young Dutch children, about three years of age old.… I took them out in a large perambulator that could take 3-4 children at once… My mother worked with the cleaners, they were cleaning the streets… One of the doctors suspected there was something wrong with her lungs and he prescribed extra food for her. My mum was given extra sugar, I got milk and curd… It was only when we returned home that we learned about mother’s TB. She was later assigned to work at the Schleusse… and, after that, to the fields where she helped picking spinach….. She was eventually sent to work with cows and stayed there until the end. She could bring some milk back from work, before that she used to bring spinach and nettles… We were given food stamps that could be exchanged for bread and margarine. We were nevertheless able to make most of things that mother brought back from work… There were also some things that could be bought in stores, my mother used to by some sort of essence that she then sprinkled over that salad of ours….

By the end of our time there, we had moved into a room of our own somewhere at the corner near the square. At the time we thought the place was like heaven, it even had a lot less bed bugs than the old one. Our room was soon well-known and served as an example to others, it was even presented to Germans during an inspection in the spring… My mother met a Danish family in the ghetto which received Red Cross packages often, with bacon, lard and other delicious things. She traded those in for our jewellery (that we managed to smuggle into the camp) and thus we spent all of our valuables on food in the ghetto.

Unlike other prisoners, the Slovaks were relatively well informed about what actually went on in Auschwitz. Among other things, they had information from the Alfred Wetzler and Rudolf Vrba report, the two having escaped from Auschwitz in the spring of 1944 and having presented testimony of the Auschwitz camp.

Ing. Zuzana Veselá, born Gescheidtová was born on 28 September 1931. She was 13 years old when she arrived at Terezín. She survived, along with her mother and sister. Our article quotes excerpts from her memories of her persecution and imprisonment in the Terezín ghetto (APT 2226). Up to present day she cooperates with the Terezin Memorial and takes part at the meeting with teachers.

Se

Zuzana Veselá during the meeting with the Slovakian teachers at the seminar in the Terezin Memorial: