The Terezin involuntary community gave birth to binding legal standards, which were exercised there throughout its entire duration. “Each ghetto inhabitant is obliged to obey all rules and regulations. Violation of them will be punished.” So was it determined in the general and special camp orders issued by the SS command in early 1942, and further modified and amended by the Jewish self-government in 1943 and 1944. The self-government headed by the Jewish Elder /Judenältester/ was empowered by the SS to run all the ghetto: from administration and registration through work assignment, accommodation, meals, maintenance, supplies, health and social care. Department for resolving legal issues and the court belonged to the internal self-government administration. The SS much endeavoured that the “independent jurisdiction” convinced the public and external guests of common civilian conditions prevailing in Terezin.

Who was authorised to try prisoners’ transgressions?

Of course, in such large and diverse community of people, issued regulations were violated very often. There were altogether six instances which made decisions and punished: ghetto headquarters, ghetto court and youth court, district and block elders, commander of the detective and security department, Jewish elders and Conciliation Commission. The SS command all the time reserved the right to intervene in the Terezin laws, to change the judgements and confirm them. The ghetto commander could use up the capital punishment as well as grant a pardon. For example, in early 1942 commander Seidl ordered to hang 16 men who had violated some parts of the ghetto order (had sent letters, had maintained contact with people outside, etc.). No more executions have been held there, as later transgressors were sent by close transports eastwards or transferred to the Gestapo prison in the Small Fortress.

Ghetto Court

Plan with the designation of districts and the location of the courthouse in the ghetto (green line)

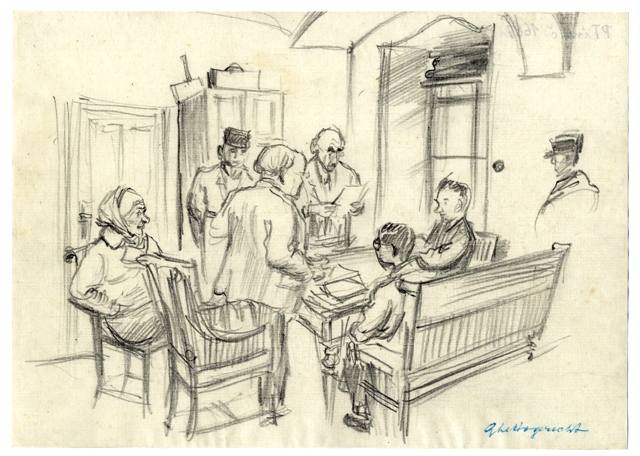

The premises of the Ghetto Court (Ghettogericht) were located in the former Terezin town hall. Judges (a three-membered senate) kept required management forms applicable in civil life: presence of the defence, voting on the sentence, records taking, possibility for the defendant to appeal. For two years, the Ghettogericht Chairman was Dr. Heinrich Klang. He was deported to Terezin from Vienna in September 1942 at the age of 67, and ranked among the prominent ones due to his pre-war merits in law. He remained until the liberation and became famous for his estates vanity and rigorous approach.

What was the subject of discussions at these penal authorities?

Within the work discipline, it was e.g. non-observance of working hours, low work performance or unjustified breaks. Usually punishments, like reprimand, extra labour task, withdrawal of bread dose or prohibition to go out after work up to a fortnight, were imposed.

Within the criminality, the penal authorities in ghetto dealt with other offences. See the following statistics from 1942, when 5,183 offences in total were registered and classified as:

- – theft: 72 %

- – incorrect inheritance treatment: 12 %

- – guard offence: 11 %

- – fight: 2 %

- – deception and embezzlement: 2 %

- – slander: 1 %

First place takes theft, mainly caused by the insufficiency of food, which was for each inmate the primary means to survive. This ghetto activity is called Schleuse/Schleusen, and under this term is understood to “get” things from the common in an unauthorized manner. Schleusened were vegetable in field, bread or potatoes from vehicles during the distribution in camp, clothes and other things of daily use from the storages. According to rules, criminal prosecution and penalties followed. They could be:

- – Exclusion from employment associated with the benefits of better catering, or from any food operation,

- – Exclusion from the benefits of better housing,

- – Imprisonment for a fixed period of time (prison facilities were in Dresden and Sudeten barracks and in the cellars of the SS Command),

- – Withdrawal of certain foods,

- – Confiscation of belongings in favour of the community,

- – Public stigmatizing (daily orders regularly stated persons convicted and punished).

Supervision of sentence execution also belonged to the Legal Department.

The case of Frantisek Kraus

Barely 17-year-old Frantisek Kraus, along with Jiri Weiss, supplied food for Heim Q 710, where they were placed. One morning in 1943 they were accidentally given an extra box of cakes in the kitchen. Both of them noticed that, but did not return the food. “Let us eat properly for once”, they thought. The breakfast was thus unexpectedly rich even for the other boys from their quarters. It came out and the act, judged as theft, became investigated by the “criminal police” of the ghetto. The boys were brought to trial – the first act of youth court. Both adolescents were defended by educator Fredy Hirsch. Although he emphasized their so-far clean records and the fact that they did not steal, but only failed as ration distributors, and that the food went equal among other boys too, all was in vain. Both of them were sentenced to deportations eastwards. Jiri was listed first, in September 1943, and Frantisek followed him in December 1943. Only F. Kraus lived to see the liberation.

Escapes

Escape was the most severe offence in every CC. In Terezín, any unauthorized leave of the ghetto was assessed as escape. There have been recorded the following numbers of escape failures: 1941 – 3, 1942 – 11, 1943 – 14, 1944 – 9. As full families often were present in the ghetto, there was a warning issued that members of family would be punished together with the escapee. That is why there were so few attempts to escape there. However, not only individuals were punished, often many-day collective punishments were imposed too, e.g. in April 1943, after several people’s attempt to escape had been revealed.

Ausgehsperre – a term meaning a curfew. Only those who went to work or for food were allowed to leave the quarters.

Lichtsperre – a very severe punishment, where no light could be put on, incl. common spaces.

Freizeitgestaltung stop – prohibition of all cultural events.

After the departure of large transports in autumn 1944, the Terezin legislation more or less collapsed. Nevertheless, the whole legal comedy had not finished yet, as shown in other circulars with regulations of the secretariat’s government from Spring 1945. People still had to respect injustice. It was a unique situation in the history of all similar facilities and concentration camps.

Chl