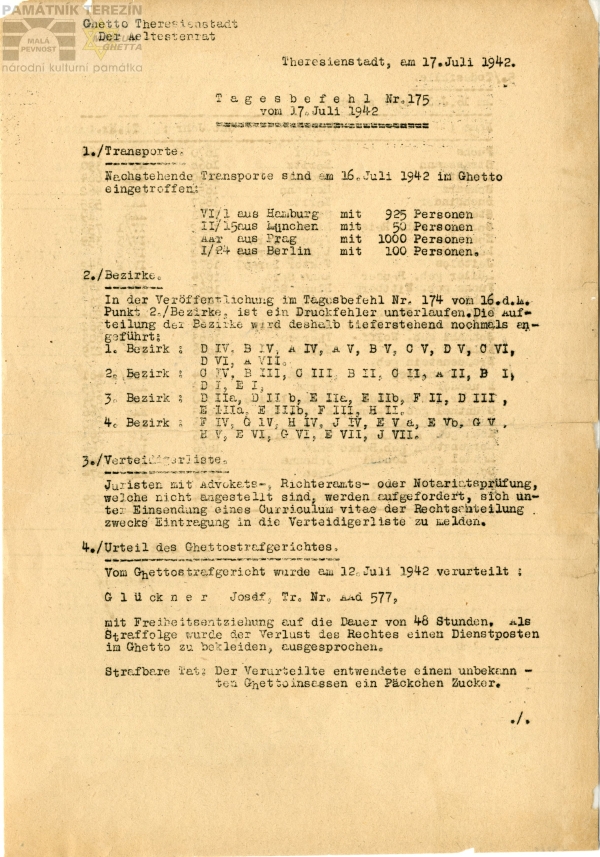

Announcement – arrival of the German and Austrian transports to the Terezin ghetto in Daily order; A3262

“On 2nd June 1942, 50 people arrived in the Terezin ghetto by transport I/1 from Berlin.” In such a curt way did so far only Protectorate prisoners (from Bohemia and Moravia) learn about the arrival of the first German speaking Jews from the daily command of 3rd June.

Those transports were specific. Last groups of original inhabitants were leaving the ghetto vacating so their civilian houses to prisoners, whereas transports of very old people were arriving. Not families (which used to be the case of Protectorate transports), but people at the end of life (the average age of German prisoners was approx. 65 years). They came completely alone, without younger relatives who would be able to support them in the ghetto conditions.

Transports from these areas kept coming to the ghetto regularly since then being of different size: large (several hundreds of people), small (e.g. 50 or 100 people came regularly by transports from Berlin, Munich and Dresden) and “EZ transports” – Einzelreisende (“single passenger”). The last German transport arrived in the ghetto in April 1945.

Formally, these transports differed from the Protectorate ones with its marking: instead of alphabet letters, German and Austrian transports used Roman numerals (e.g. Roman I marked transports from Berlin, II from Munich, III from Cologne etc.).

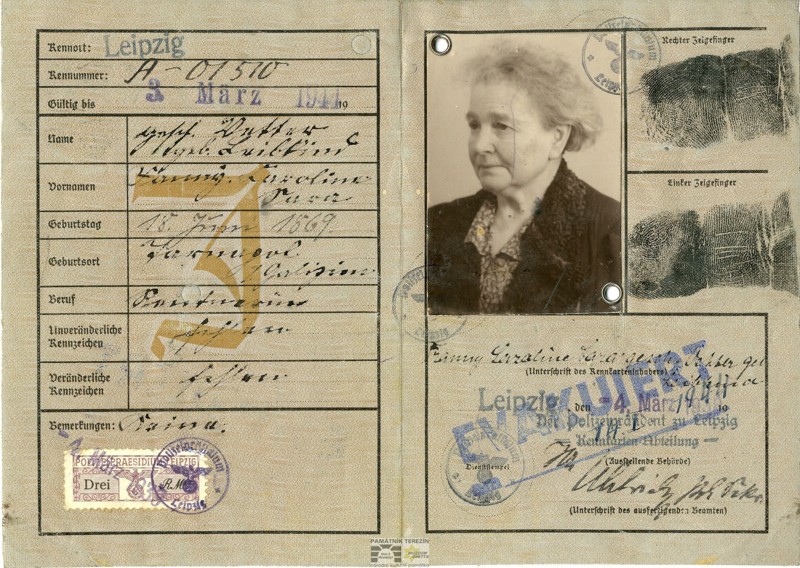

However, what made these transports unique was mainly a very refined Nazi plan supporting them. On one hand, Nazis needed some explanation for why they were getting rid of their meritorious citizens (many of transport members felt Germans; they were important personalities of the political, scientific and cultural life; numerous transport members had also been decorated with high honours after the 1st World War for their fight for the homeland, Germany). On the other hand, Nazis needed in all sorts of ways to conceal the fact of the enormous extermination of Jews which had been under way in the “East” for several months already. Their solution was incredibly cruel especially to those German Jews. They were given the deportation to Terezin as a “privilege” for their merit. “Wealthy” German Jews (those whose assets exceeded 1000 Reichsmarks) had to conclude a “contract to purchase a house” in Terezin – that again supported the idea of a mere relocation (rather than imprisonment or ghettoization) and the myth of a privileged ghetto at once. If a Jew was reluctant to sign the contract or board the transport, they were sarcastically threatened with a deportation to “concentration camp”. In Austria, such contracts were not used, the transport policy was similar to the Protectorate one there. In both Germany and Austria the property left by Jews in their homeland fell after some time to the state under the imperial law.

Kennkarte issued for Vetter Fanny Caroline in Leipzig in March 1944, A 10882

The myth of a privileged camp at once corresponded with the Nazi cover-up manoeuvres following the conclusions of the Wannsee Conference near Berlin in January 1942. The conference labelled the Terezin ghetto camp the “old-age ghetto”. Unlike the “eastern transports” deporting younger groups of German Jews, the transports from Germany to Terezin were often referred to as “old-age transports” (Alterstransporte) – it again meant to support the idea of a “Jewish Town”.

It is therefore not surprising that there was a huge mortality among German and Austrian Jews in the ghetto then. People who believed in coming to a dignified “spa town” should learn the ghetto reality very quickly. High age, absence of family members, a sense of injustice to Germany and all life disappointment at all – that all had impact on their psyche (nearly half of all German prisoners died in Terezin). Besides, large part of them was destined a different fate.

The Terezin ghetto experienced in the culminating summer of 1942 its first wave of overpopulation coupled with the outbreak of lice. Likewise, the proportion of older and elderly people to work capable ghetto members considerably equalized. The Nazis resolved the situation in their way. From September 1942 the “unemployable” German Jews (often on the verge of death) began to be in thousands officially dispatched to the “other nursing ghetto”, i.e. mostly to the extermination camp in Treblinka.

The final balance is ominous: out of the total of more than 42,000 prisoners deported to Terezin from Germany only less than 6,000 people survived the war, and out of more than 15,000 people deported from Austria only 1,300 of them survived.

Kl