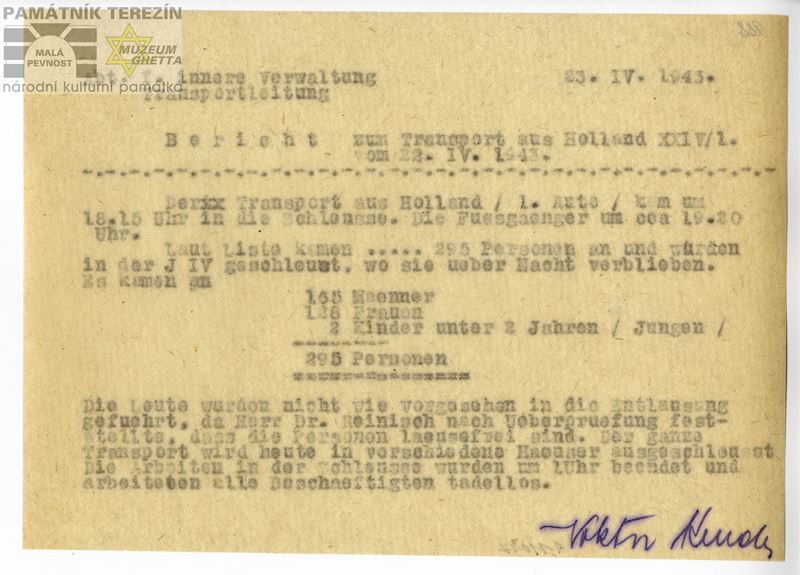

Report on the arrival of the transport XXIV/1 from Holland to the ghetto Terezin in April 1943. PT 11017.

Curt announcement in daily order of 23rd April 1943 let the ghetto prisoners in Terezin know about the arrival of transport marked XXIV/1 with 295 people from Amsterdam on 22nd April 1943. Seven more transports gradually arrived until November 1944.

The above mentioned eight transports were composed of nearly 5,000 people mostly interned in the Westerbork camp. This camp was founded as early as in 1939 for Jewish immigrants from other countries. Since the spring of 1942 transports of Dutch Jews were dispatched there and with the beginning of summer they started leaving to “the East”. Approximately 100,000 Jews were deported over Westerbork.

Speculations about the possibility of sending transports to Terezin appeared there in October 1942, in connection with the question of how to treat the Jewish fighters of the First World War. Nazis considered Terezin suitable for them, because similar “cases” of the Reich had also been sent there. In the Netherlands, Terezin was seen as a better option for deportation to the East, it was understood as a ghetto of the old, a place where it is possible to get for merits or retirement age.

In January 1943 the criteria for selection into the first transport to the Terezin ghetto were specified: among the qualified were, for instance, holders of the first class Iron Cross, holders of relevant Austrian honours, and women who had been decorated as nurses during World War I. They were allowed to take along their husbands and children under the age of 14 as well as others. The set of criteria for the next Terezin transports became then expanded.

Life in Terezin

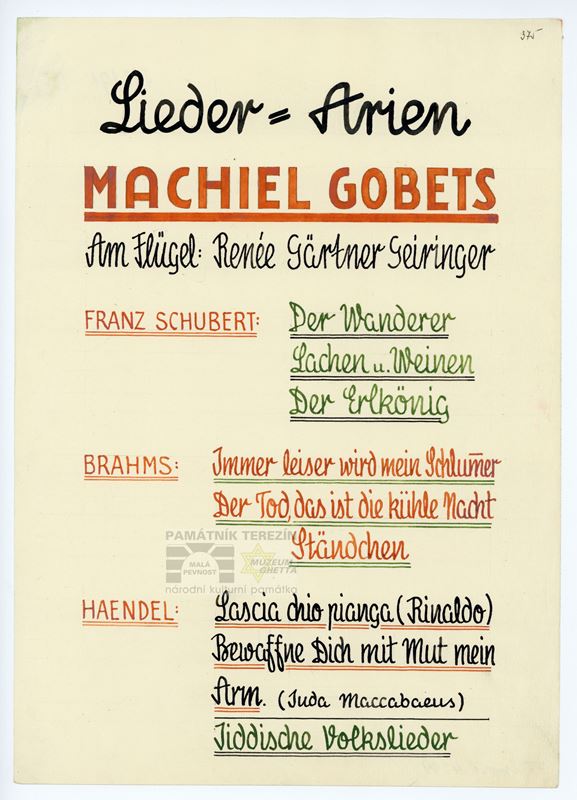

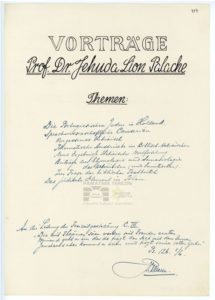

List of the lectures by prof. dr. Jehuda Lion Palache. PT 4119, Památník Terezín, Heřmanova sbírka, © Zuzana Dvořáková

The Dutch were the fourth large group in Terezin that came here after the Protectorate, German and Austrian Jews. Their great hopes and joy arising from the fact that they had not been included in transports to Auschwitz were soon dashed after they discovered that transports to the East departed even from here.

Dutch transports represented a mix of people of different nationalities. There were many German Jews living in the Netherlands since the 1930s, who had fled there as the result of persecution in Germany. Upon arrival in the ghetto, the deported from the Netherlands were divided into two groups by their country of origin, the “German Dutch” and the “Dutch Dutch” (as was the case in Westerbork too). The German Dutch were more involved in the camp life and in work. They had no problem in terms of language. Many of them met here their friends from the time before their emigration. Those already aware of the situation in the ghetto helped them to get better work and provided them with valuable information essential for life here.

The Dutch Dutch were in terms of language slightly disadvantaged. Those Dutch coming from wealthier and more educated classes also usually spoke good German, since before the war there had been put an emphasis on teaching languages in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, the life of poorer Jews, uneducated workers, was harder in Terezin for their ignorance of German language, and they had to make themselves understood in any possible way. Often they learnt some Czech words too.

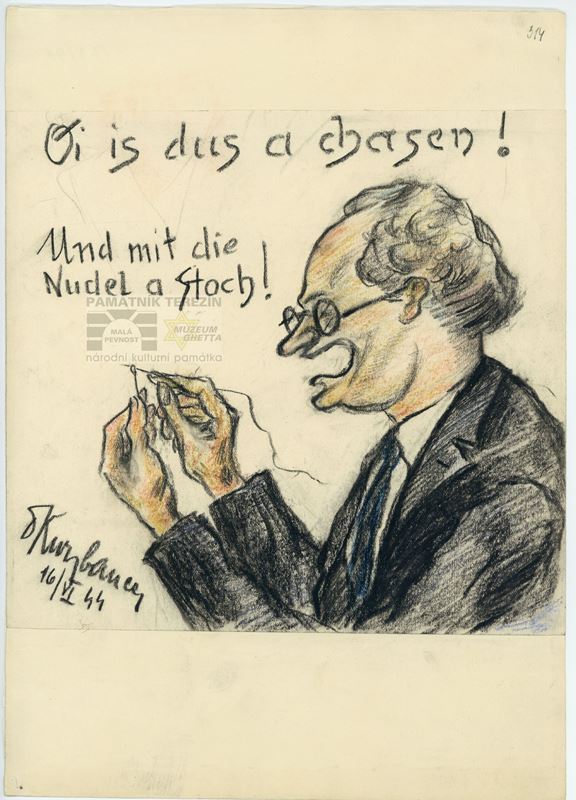

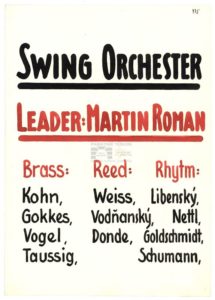

Photo of M. Roman on the commemorative note for K. Herrmann. PT 4185, Památník Terezín, Heřmanova sbírka, © Zuzana Dvořáková

Good relationships among prisoners in the camps in general were never the interest of the Nazis – disintegrated community brings always better conditions for obtaining “material” for transports to the East. In Terezin, this idea was supported, after the arrival of Dutch transports in the winter of 1944, by the fact that about 3,000 women deported from the Protectorate had to move out of the Hamburg barracks where they had lived until that time because of the newcomers. That naturally cast bad light on them. Moreover, the Dutch were not usually housed in the ghetto together, which also made it more difficult for them to cultivate cohesion.

Only a few children from the Dutch transports were placed into children homes. It is very likely that their parents were informed of this possibility, but in the new situation upon the arrival of transports, when they felt mostly hungry, tired, and after they had been deprived of most of their property, at that moment they had no wish to put their children in youth and children homes. In spring and summer 1944 rabbi Jehuda Palache co-organized Dutch classes. Short time there was also a Dutch preschool in operation, and a Dutch children home for children up to 14 years was formed in the Hamburg barracks where large part of the Dutch was staying. Its capacity reached up to 100 children.

Flyer announcing the existence of the Swing orchestra in the ghetto with Martin Roman as a leader. PT 3979, Památník Terezín, Heřmanova sbírka, © Zuzana Dvořáková

The Dutch considered the Terezin diet insufficient, but according to the notes in their diaries, they were pleasantly surprised by the Czech cuisine, especially by “buchtičky se šodó“(sweet buns in custard sauce) and dumplings. The Dutch quite successfully joined the illegal trading in the ghetto. They changed for money, exchanged their personal belongings – e.g. a lipstick for half bread. Another of the Dutch working in the vegetable garden at the Small Fortress offered smuggled vegetables throughout the summer of 1944. For that reason he wore specially adapted long tights.

Among the distinct personalities who came to Terezin from the Netherlands was e.g. Jo Spier. Even here he was a draftsman and worked in the drawing room. Many Dutch people found jobs in the health care in the ghetto. After the departure of autumn transports in 1944, they took over the abandoned positions of health professionals. Jews from the Dutch transports were to a large extent active in music, lecturing and cabaret performances. Film director Kurt Gerron and jazz pianist Martin Roman, both German Jews, significantly contributed to the cultural history of the ghetto.

Around 2,800 Dutch people were deported from Terezin to Auschwitz. 163 Dutch found their death in Terezin.