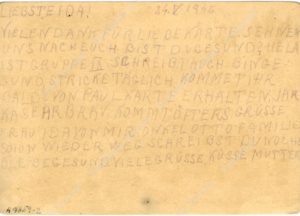

For the Ghetto Command, correspondence through postal services, as a tool of communication between inmates and the outside world, was the most closely monitored sector subjected to special regulations. Following various restrictions imposed in the first months of the Ghetto’s existence, regular postal service began to develop in September 1942. When corresponding with the outside world, prisoners had to adhere to a number of continuously adjusted conditions, but essentially it was vital to meet the following rules: easily legible messages had to be written exclusively in German and were not allowed to exceed thirty words or a single page of a small postal card. The field of prohibited topics was also strictly defined – texts with political content were inadmissible, writers were not allowed to use abusive language about the Reich and its leading representatives, the ban also covered any negative information on the living conditions in the Ghetto etc. Generally speaking, these restrictions inevitably resulted in more or less uniform messages claiming that the writers were well off.

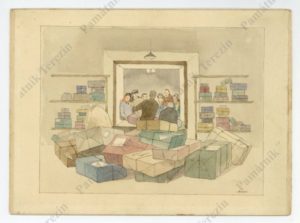

Charlotta Burešová: At the post-office – parcel counter, 1942 – 1945, Památník Terezín, PT 12468, © MUDr. Radim Bureš.

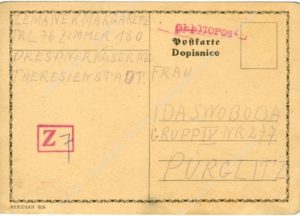

Special attention was accorded to censorship. The inmates used special postal cards for writing letters, getting them through Terezín´s Jewish Self-Administration. A written letter then went into the hands of a censor in the camp’s Jewish Self-administration. The censor checked the content of the letter and stamped it with letter “Z“ (referring to the German word Zensur = censorship) and with its own censor’s number. In this way, the censor assumed responsibility for the harmless content of the letter, which could then be passed on to another round of censorship, this time at the SS Command. Only after being checked by SS officers could letters be sent off from Terezín. If the addressee was an inhabitant of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia the letter was sent from Terezín by courier service to Prague’s Center for Jewish Emigration, where employees of the Jewish Community collected the letters, sorted them out, and only then sent them by mail to addressees.

Owing to the Ghetto’s enormous captive population and also due to the limited capacities of the prison office staff, who censored the mail, registered it etc., the inmates were allowed to send letters only within well-defined cycles. The length of such cycles was continuously changed and ranged approximately from two to three months. If a writer violated the regulations given for postal correspondence, for instance due to his letter’s content or layout, it was returned to the writer by the prison censor with the possibility of promptly writing a new letter. If a second letter also failed to meet the stipulated rules, the writer had to wait for his turn in the next cycle. In spite of the given cycles, introduced due to time-consuming administration of the prison correspondence, its overall volume reached enormous dimensions.

In addition to inmates´ official correspondence in the Ghetto, there also existed an illegal channel through which prisoners dispatched and received mail from their relatives and friends. Some of the local gendarmes and other individuals were engaged in this clandestine system of letter delivery.

Postal card from the Terezín Ghetto from Margarete Zemanek to Ida Svobodová, dated 24. 5. 1942, with the sign of the sensor, 1. page, APT A 7859/K43/Gh.

One of the persons selflessly helping inmates was, for instance, Josef Bleha from Terezín who had a small tobacconist’s shop in the town. The early days of his contacts with the inmates dated to the very beginnings of the Ghetto and continued even after the abolition of the town of Terezín in February 1942 and after Bleha´s subsequent moving to neighboring Bohušovice. In the spring of 1943, the Gestapo had ferreted out his illegal contacts and Josef Bleha was arrested and jailed in the Gestapo Police Prison in the Small Fortress. He was later deported to a German concentration camp. He had returned to Bohušovice after the liberation but he kept silent about his wartime support of the Terezín inmates. In recognition of his acts of humanity Josef Bleha received postmortem the title “Just Among the Nations”, awarded by the Israeli Holocaust Memorial Yad Vashem.

Postal card from the Terezín Ghetto from Margarete Zemanek to Ida Svobodová, 2. page, APT A 7859/K43/Gh.

The prison postal services handled, apart from private letters also the camp’s official mail, parcels etc. Parcels addressed to inmates sometimes came to Terezín opened or their contents were partly stolen; moreover, the local SS Command occasionally seized some deliveries and never gave them to the inmates. This applied especially to parcels sent to the Ghetto by various foreign organizations without the designation of a specific addressee. The situation was better with parcels addressed to specific inmates; acknowledgements of receipt, introduced in mid-1943, contributed to greater probability that the addressee would get his delivery. The same period also saw the introduction of the so-called “allowance stamps” used by the SS Command for regulating but, in actual fact, for reducing the number of parcels sent to the Ghetto.

Many inmates were not at all affected by the above measures since they had nobody outside the Ghetto to send them any parcels. Those lucky ones, who had happened to receive parcels before the introduction of allowance stamps more frequently, were suddenly deprived of them since the acquisition of an allowance stamp had, once again, been subordinated to the stipulated cycles, outside of which parcels could not be sent to Terezín. But these allowance stamps had yet another function – thanks to the accurate system of record-keeping listing the actual senders of parcels, the Nazi Police in the Protectorate had a good knowledge of those inhabitants in Bohemia and Moravia who sympathized with the Jews jailed in Terezín in this way.

Each sender was obliged to insert into his parcel a precise list of contents to be checked out during the delivery in Terezín in the presence of the addressee. Parcels were not allowed to contain prohibited goods, such as cigarettes, tobacco, watches etc. In spite of all those restrictions, parcels meant a considerable improvement of recipients´ living standards. For their part, fellow prisoners often felt envy because parcels not only improved addressees’ material wellbeing but also gave them so urgently needed food. Food parcels in particular were a special temptation for the inmates employed in the Terezín post-office. Some of them, tormented by hunger, could not resist the temptation even though captured thieves were given severe punishment.

The central post-office in the Ghetto changed its location several times during the war. For instance, the building of the former armory, the ground premises of object L 414 in the town square (today’s house No. 612) and other buildings were used for that purpose.

Šm