A special transport codenamed Dx, consisting exclusively of mentally ill patients from Terezín´s psychiatric ward, left the Terezín Ghetto on March 20, 1944. In addition to 42 inmates-patients, the transport carried a three-man accompanying team, made up of two male nurses (Kurt Andermann and Ernst Grünfeld) and one doctor (Dr. Walter Ruben). According to nurse Marie Schnabelová this transport actually marked the end of the psychiatric ward in the Kavalier building (E VII), as its existence evidently did not fit into the Nazi plans for the ongoing “beautificationˮ of the Ghetto.[1] After the departure of the transport, two rooms in the psychiatric ward in the Kavalier were made available to the Nursing Care Department (Siechenfürsorge).[2]

Transport Dx itself stood out as a rare case among other transports from Terezín; an overview of the deportations of Terezín inmates for the years 1941-1944, prepared by the Terezín Self-administration, mentions the transport only with a note ”Psychiatry 26. 3. 1944“.[3] The records of the division known as Institutional Care in the Terezín Health System from March 1944 stated that”[…] E VI: On March 19 and 20, an outgoing transport from the psychiatric ward was furnished with the essential necessities and prepared for its journey.“[4]

According to the available literature penned by domestic and foreign historians, the above mentioned transport Dx was destined to have arrived in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.[5] The assumption that this particular camp was, indeed, the final destination of the transport could have been further strengthened by the fact that the transport had not been entered in the Auschwitz calendarium compiled by historian Danuta Czech among the incoming transports to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, as was the case with other transports that had come to the camp from Terezín.[6]

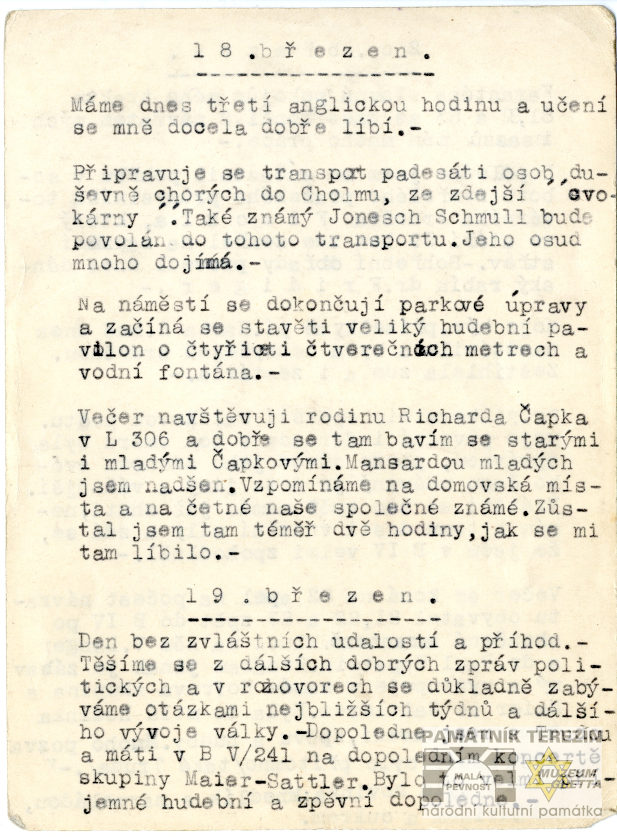

The dispatch of transport Dx did not go unnoticed in the Ghetto. Egon Redlich as well as Willy Mahler wrote about in it their diaries. The former noted: “50 people from the lunatic asylum will be dispatched to the East.”[7] and the latter specified the destination of the transport: “Transport of the mentally ill inmates from the local madhouse to Chołm is getting ready. Also the well-known Jonisch Schmul will be sent in that transport. Many people here are stirred by his plight.ˮ[8]

Thus, Willy Mahler mentioned Chołm as the destination of the transport carrying mentally ill inmates from Terezín in March 1944, and he certainly had not made that up. Most probably it was the SS command that had intentionally spread the name of the destination among those most concerned. It should be noted that already in the past psychiatric hospitals had mentioned Chołm as the destination of their fictitious transfers of Jewish mentally ill patients, doing so with the aim of hampering the tracking down of the real fate of such inmates during the liquidation operation, known as “euthanasia organized by the criminal Nazi regime in the years 1939-1941”. In their works historians Henry Friedlander and Wolfgang Neugebauer have charted and exposed this deception involving the fictitious institute, a ruse that had been practiced on the Jewish communities in Germany and Austria. The psychiatric institute in Chołm had really existed but was closed down already in 1940, and a sham registry office was later established serving as a front to cover up the traces of the liquidation of Jewish mentally ill patients in the extermination institutes in Germany and Austria.[9] The question is why did the SS revert to its earlier legend about Chołm and spread it among the Terezín inmates? Why did not the SS command simply include the mentally ill inmates into a transport dispatched to the Auschwitz camp?

That the final destination was, indeed, Chołm proved to be impossible because, as emphasized above, not even the earlier transports in the years 1940–1941 could have reached the real Chołm due to the reasons given above.[10]

The difficulties in tracing the genuine fate of the transport Dx are caused by the absence of a single document proving the transfer of the mentally ill inmates from Terezín either to Auschwitz-Birkenau or to Bergen-Belsen. As a result, the key tool and guideline to correct identification of the transport´s final destination has been found in the memoirs of Holocaust survivors and also in the reconstruction of the fates of the accompanying personnel of those mentally ill patients. This reconstruction could be performed only under the assumption that the accompanying staff had not been murdered along with their charges.[11]

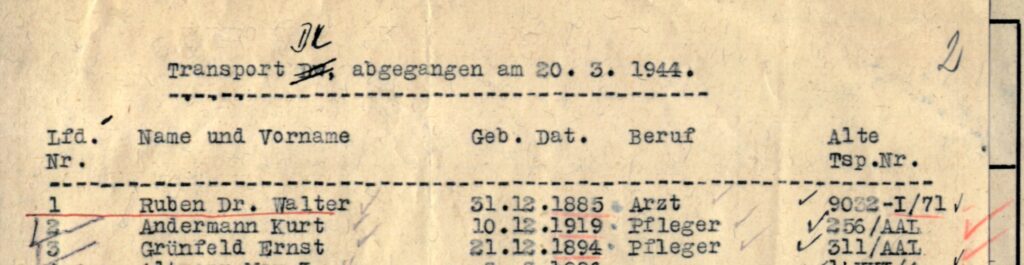

The mystery of the actual final destination of the Terezín transport Dx was finally solved by piecing together snippets of information on the fate of one member of the accompanying team of carers, Kurt Andermann. Thanks to that picture it is evident that, after all, the final destination of the transport Dx was the Auschwitz Jewish ramp.

Yakov Tsur recalled that Kurt Andermann had come to his block in the Terezín family camp in Auschwitz and informed the inmates that the SS officers had told the accompanying personnel: “Die Wahnsinnigen werden ihrem Schicksal entgegen gehen, aber ihr kommt ins Lager.“[12]

Dr. Gottfried Bloch in his book Unfree Associations recalls the arrival of Kurt Andermann from the Dx transport as follows: “We received only one newcomer from the next train, a trained psychiatric expert who had accompanied the group of patients from the psychiatric ward in Terezín. All the patients from that train went into the gas chambers. I heard about grotesque scenes in the anterooms masked as washrooms where inmates undressed. Some psychiatric patients, displaying utter ignorance and indifference to their plight, even greatly upset the SS officers […]“[13]

Kurt Andermann passed “selectionˮ in July of that year and on July 7, 1944 he was sent, together with another one thousand men from the Terezín family camp, to the branch of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Schwarzheide. There he worked with other inmates on clearing away rubble after an air-raid on the coal liquefaction plant Hydrierwerk Brabag Ruhland on June 21, 1944.[14] According to testimony he died in the camp sometimes in March 1945.[15]

Why did the SS camp command use that “legend” of Cholm when the destination of the transport was the concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau? This was primarily due to two major reasons that served to cover up the genuine fate of the transported inmates: The first one concerned the plans the Nazis had in store for the Terezín inmates deported to Auschwitz–Birkenau between September 1943 and May 1944. In September and December 1943 Terezín Jews, inhabitants of the Protectorate, were deported to one section of the Birkenau camp – the Terezín family camp – for the purpose of camouflage; its real reasons are still unknown to us.[16] The Terezín SS command probably knew the goal and purpose of these transports, passing off these deportations of Terezín inmates for labor transports (those in September 1943), eventually for transports to the Reich (those in December 1943), and it is easy to understand that due to the proclaimed purpose of the transports, a greater number of mentally ill inmates could have hardly been included. Since written communication existed between the Ghetto and Birkenau,[17] it was not quite possible for the SS command to let the Ghetto inmates know that mentally ill patients had been sent to places from which they themselves received postal cards with senders´ addresses: “Labor camp Birkenau near New Berun” (Arbeitslager Birkenau bei Neu-Berun).[18] Any connection between deportations of these patients and the labor camp would have caused distrust and doubts in Terezín´s coerced community. And that was why the legend of the Chołm institute had to be revived.

Another proof exposing the Nazi camouflage in this case was the inclusion of one Danish inmate in the transport to the East. This involved Jonisch Schmul Sender (b. 1899), who according to testimony: “[…] soon after his arrival attracted our attention. A perfect example of Polish Jew, constantly cowering and praying, almost unheeding of his accommodation, his hygiene and his nourishment. He comes from Poland and he lived in Holland for a long time. Then he got to Denmark where the German authorities detained and deported him to the Ghetto. He speaks Polish, German, Danish, English and perfect Hebrew. His credo is the duty of constantly praying for the wellbeing of others. The leading officials in our barracks (i.e. Hannover Barracks (H IV) – note TF) are now seriously discussing his problem since Jonisch does not work and refuses to work, out of the meager food provided here he eats next to nothing, thus failing in his heath, both mentally and physically.”[19]

Under an agreement between Dr. Werner Best, the Reich plenipotentiary in Denmark, and Adolf Eichmann from the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), the Danish Jews were to be protected from transports “to the Eastˮ.[20] It is worth mentioning that by including this particular inmate into the transport the SS camp command violated the agreed proceedings concerning the Danish Jews staying in Terezín. On the other hand, precisely this move to include an inmate from the Danish transport to the above mentioned Dx transport served to calm down the Ghetto inmates by telling them not to worry about the fate of the deportees, and to hoodwink the Danish inmates in case the delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross would enquire about the fate of all the Danish inmates during its planned visit to the Ghetto. The fact that Jonisch was sent in that transport and the general knowledge that the Danish inmates were thus protected could convince the Ghetto population that the transport was, indeed, going to the mental institute in Chołm. However, this was another in a series of ploys to cover up the real purpose of the transports – namely the liquidation of Terezín inmates after their deportation from the Terezín Ghetto.[21]

Tomáš Fedorovič

[1] YVA, O.2/1120, Schnabel, Marie: “Nursing mental patients in Theresienstadt” [online], http://collections1.yadvashem.org (checked on April 14, 2014).

[2] ADLER, Hans Günther: Die verheimlichte Wahrheit, Theresienstädter Dokumente, Tübingen 1958, p. 208 (in German).

[3] YVA, O.64/33, Die Bewegung des Bevölkerungsstandes vom 24. 9. 1941 – 31. 7. 1944 [online], http://collections1.yadvashem.org (checked on April 14, 2014). Date in the overview is given incorrectly.

[4] ADLER, H. G.: Theresienstadt, p. 542 (in German).

[5] For the information that the transport arrived in Bergen-Belsen, see: Hans Günther Adler, Theresienstadt 1941-1945. Das Antlitz einer Zwangsgemeinschaft, Tübingen 1960, p. 178 (in German); LAGUS, Karel – POLÁK, Josef: Město za mřížemi (Town Behind Bars), Prague 1964, 20062, p. 246 (in Czech), and KÁRNÝ, Miroslav: Konečné řešení. Genocida českých Židů v německé protektorátní politice (Final Solution. Genocide of the Czech Jews in the German Protectorate Policy). Prague 1991, p. 156 (in Czech).

[6] That was transport Eh on July 1, 1944.

[7] REDLICH, Egon – KRYL, Miroslav (ed.): Zítra jedeme, synu, pojedeme transportem (We are going tomorrow, son, in a transport), Brno 1995, p. 89 (entry from March 19, 1944) (in Czech).

[8] PT, A 5704 – 5, diary of Willy Mahler, entry on March 18, 1944.

[9] Friedlander, Henry: Jüdische Anstaltspatienten im NS-Deutschland. In: Götz, Aly (ed.), Aktion T4 1939-1945, Berlin 1989 (= Stätten der Geschichte Berlins 26), pp. 34-44, zur Erforschung der nationalsozialistischen „Euthanasie“ und Zwangssterilisation (ed.), Beiträge zur NS-“Euthanasie”-Forschung 2002, Ulm 2002 (=Berichte des Arbeitskreises 3), p. 129–145 (in German).

[10] Miroslav Kryl ranks among the few historians who, in his summary of the overview of transports, correctly states that historians are wrong and that it was impossible for all the four transports, i.e. Dx, Eh, Eg and Ej, to end up in Bergen-Belsen, and then he inexplicably adds: “[..] Now I deem this certainty weakened and I believe that the deadly destination in case of the transport from the turn of June and July could be Chelmno (Chołm) (here the author undoubtedly erroneously means transport Eh, which, however, ended in Auschwitz – note TF), in the other cases (or in all four) Auschwitz-Birkenau.” Cf. KRYL, Miroslav: Obraz terezínských deportací na Východ v deníku Willyho Mahlera (Picture of Terezín Deportations to the East in Willy Mahler´s Diary). In: KÁRNÝ, Miroslav – KÁRNÁ, Margita – BROD, Toman (eds.), Terezínský rodinný tábor v Osvětimi-Birkenau (Terezín Family Camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau), Prague 1994, pp. 161–162 (in Czech). But in 1999 M. Kryl asserts that the transport was directed to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

[11] The parallel that offered itself in this case is evident from the well-known fate of the accompanying personnel of the Białystok children. All the 53 Terezín women and men, who accompanied this transport on its alleged journey to a neutral foreign country for exchange, ended without exception, together with the children, in the gas chambers in Auschwitz-Birkenau On the problems and fate of the Białystok children cf. Klibanski, Bronka: Děti z ghetta Bialystok v Terezíně (Children from the Bialystok Ghetto in Terezín), in: TSD 1996, pp. 71–84 or Greenfieldová, Hana: Z Kolína do Jeruzaléma. Střípky vzpomínek (From Cologne to Jerusalem. Snippets of Memories), Prague 1992, pp. 48–55 (in Czech). Mother of the author was one of the nurses who accompanied the children to death.

[12] This information comes in an email “Transport Dx on March 20, 1944” sent by Yakov Tsur to the author, 22. 11. 2007.

[13] BLOCH, Gottfried R.: Unfree Associations, Los Angeles 1999, pp. 134–135.

[14] Tsur, Yakov: Schwarzheide, pobočný tábor koncentračního tábora Sachsenhausen (Schwarzeide, branch camp of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp) in: TSD 2002, pp. 203–218 (in Czech).

[15] PT, A 7289, List of the deceased at Schwarzheide and on the death march.

[16] On the problems and ambiguities relating to the establishment and existence of the Terezín family camp, see: Brod, Toman – Kárný, Miroslav – Kárná, Margita, c. d.; Fedorovič, Tomáš: Propagandistická role Terezína a terezínský rodinný tábor v Auschwitz-Birkenau (The Propaganda Role of Terezín and the Terezín Family Camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau), in: Terezínské listy (Terezín Yearbook), 46/2018, pp. 32-40 (in Czech).

[17] Cf. Adler, H. G.: Die verheimlichte Wahrheit, pp. 137–139 (in German). A memorandum submitted by the Council of Elders (by Edelstein) to Dr. Seidl said that the proposal to establish direct postal connection with the Ostrowo camp (alleged destination camp for the elderly who actually ended up in the Treblinka extermination camp) and the labor camp in Birkenau had been rejected on his part.

[18] The first mention of correspondence between the family camp Birkenau and the Ghetto appeared in the diary of W. Mahler as early as on September 15, 1943. Cf. Kryl, Picture, pp. 158–160. Inmates from the family camp (also from December transports) kept sending news to the Ghetto even later. See: Kárný, Miroslav: Otázky nad 8. březnem 1944 (Questions about March 8, 1944), in: TSD 1999, pp. 16–17.

[19] PT, A 5704, diary of Willy Mahler, entry on January 9, 1944 (”An interesting figure in B IV.“).

[20] Herbert, Ulbricht: Best. Biographische Studien über Radikalismus, Weltanschauung und Vernunft 1903–1989, Bonn 1996. pp. 372–373 (Dokument: ADAP, E VII, S. 144. Letter of Dr. Best to Auswärtiges Amt (AA), 3. 1. 1943) (in German).

[21] Sophisticated Nazi camouflage may be encountered in the Ghetto history on several occasions. In the fall of 1942 elderly inmates from the Reich and the Protectorate left to another ghetto even though their genuine destination was the Treblinka extermination camp. The Białystok children originally destined to be exchanged in the fall of 1943 did not end up in secure Switzerland but on the Auschwitz ramp and in the gas chambers in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Deportations to work in Germany, near Dresden were announced in the fall of 1944, but thousands of men and women ended their lives in the same death camp.