(October 29, 1892 Prague – October 7, 1943 Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp)

“Clean, genuine, honest, consistent. Humility and pride, perceptiveness and detachment, devotion and independence, shyness and courage in an unswerving balance,” Franz Kafka.

The year 2024 marks the centenary anniversary of the death of Franz Kafka (1883–1924), we cannot help but remember the youngest of Kafka’s three sisters, Otilia Davidová, the ‟Betreuerˮ (caregiver) from the Terezín Ghetto.

Otilie was born in Prague on October 29, 1892 to Hermann, a businessman, and Julie Kafka, née Löwy. Her brother Franz was nine at the time. Ottla, as she was known at home, had two older sisters Gabriela (called at home Elli, born in1889 – died in autumn 1942 Chelmno) and Valerie (called at home Valli, born in 1890 – died in autumn 1942 Chelmno).

Ottla and her brother Franz had a very intimate relationship. She was often the first person to whom he confided, sharing in his letters personal matters such as his aspirations, intentions, and troubles. Ottla was his favorite sister. She also showed a strong social conscience and empathy to others, traits that mirrored those of her brother. In 1914, she used to go to a blind asylum on Sundays to read books to the blind and handed out cigarettes. Already before the war, she joined the Prague Club of Jewish Ladies and Girls, founded in 1912.

Ottla probably met her future husband Josef David around this time, perhaps in the spring of 1910. Josef, who was her very first acquaintance, came from a modest background, his father was a sexton in the St. Vitus Cathedral.

When the First World War broke out, Josef David was called to serve his country and fought for Austria-Hungary. He and Ottla kept in touch by writing to each other. In 1916, Ottla rented a house in Golden Lane at Prague Castle to be able to meet Josef on the days he was on leave during his military service. Franz, her brother, also escaped from home to find peace and inspiration to write in Ottla’s house. In the winter of 1916/1917, he wrote there numerous short stories for his book, ‟A Country Doctorˮ.

In March 1917, Franz rented a two-room apartment so as not to disturb his sister in the evenings. However, he was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis later that year, in September. He took a leave of absence from his position at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Company and went to stay with Ottla at Siřem near Blšany. From April of the same year, Ottla had been looking after the farm of her brother-in-law Karel Hermann, the husband of her sister Gabriela, who had to enlist in the army. Franz was certain he would find understanding with her. He needed to break away from his fiancée Felice Bauer, from his father, from the office, and from Prague. There had been a more intimate relationship between the siblings for a year. Ottla was Franz’s trusted confidante, alongside Max Brod and later Milena Jesenská-Polaková. Franz read to her not only Dostoyevsky, Schopenhauer, Kleist, but also his own works. He spent eight months at Siřem. He wrote 109 aphorisms there, and the place inspired his later novel “The Castle”. Franz Kafka returned to Prague in June 1918. During the following six years, he often stayed in sanatoriums, but his treatment was interrupted by stays in Prague.

His sister Ottla went to Siřem to help her brother-in-law and but also to escape her despotic father. She also wanted to avoid helping in her father’s haberdashery shop (in the Kinský Palace on the Old Town Square). At Siřem, she worked on the hop harvest, fed the goats, picked potatoes, and took care of the cats. She wrote love letters to Josef David on the Italian front and improved her Czech language skills for him. Her father was vehemently opposed to her departure, deeming it a reckless fling. Even before the First World War ended, Ottla, who had only completed three grades of a junior secondary school, was already thinking about studying at an agricultural school. Her brother Franz was a staunch supporter in this, guiding her in her choice of school and even offering a loan to make her studies possible. Ottla finished her course at the agricultural school in Frýdlant and passed her final exams. She was thinking about getting a job and a possible move to Palestine, where she could put her new skills to good use. However, she was in a committed relationship with Josef.

In July 1920, she married Josef David against the wishes of her parents. It is unclear whether her decision was really based on love or stubbornness. She married a Catholic, a Czech, who, when he came to visit her parents, refused to speak German with them. Ottla’s parents could speak Czech, but they did not consider his behavior appropriate. Ottla was determined to forge her own path in life and defied the conventional expectations of an obedient girl from a middle-class family at the time. She challenged the norms instilled in her by her conservative parents. This was one of the reasons why her brother Franz had so much respect for her and was so supportive of her in the marriage. In 1920, Dr. Josef David was demobilized and secured a prestigious official position. He became the general secretary of the Union of Czechoslovak Insurance Companies, a great career advancement. He had an adequate income, but it was nowhere near as much as his brothers-in-law, the husbands of Ottla’s sisters.

Věra, Ottla’s daughter, described her mother as a cheerful and honest person who liked chatting with people. Ottla was popular everywhere she went and treated everyone equally, regardless of their social status. She was modest and humble, and had a strong aversion to lying. She hated cruelty to animals. Ottla was lively, emotional, spontaneous, and full of energy. Her husband Josef was unpleasantly thrifty and had little sense of humor. He was cold and emotionally reserved, but he also had a hard time controlling his outbursts of anger. Ottla had to submit a statement of domestic expenses to him for inspection. Josef David was not allowed to know that Ottla also hosted beggars, poor and abandoned people, as well as his own visitors. Later, her guests included German Jews who had fled their homeland after Hitler came to power. Ottla certainly lived in less affluent circumstances than her sisters, who were married to wealthy Jewish businessmen. In 1910, Elli married Karel Hermann, the son of a wealthy Jewish landowner from Siřem. They had a son and two daughters together. Her sister Valli, one of the first teachers at the Prague Jewish School, married Josef Pollak in 1913, with whom she had two daughters. In both cases, the marriages were prearranged.

Ottla and Josef had two daughters shortly after their wedding. Věra (1921–2015), married Saudková, later became an editor and translator from German to Czech. Helena (1923–2005), married Kostrouchová, later Rumpoltová, worked as a doctor in Kašperské Hory. The Davids’ third child died. The girls were properly baptized, their parents did not enter them in the Jewish register. They celebrated Christmas and all Christian holidays at home. The girls used to go to their grandparents, the Kafkas, for Jewish holidays. Ottla’s father finally took her husband to his mercy thanks to his beloved granddaughters. The Davids used to have a maid at home, usually a girl from the countryside. Ottla also had a dog, a fox terrier bitch named Bělinka.

Mr. and Mrs. David were separated on February 24, 1940. Ottla lost her protection against deportation by taking this step, but at the same time she no longer endangered both her (according to the Nazis) Aryan husband and especially her daughters with her Jewish origin. The family held their separation against Josef, convinced that he was selfishly protecting his career as a well-placed official. He was also threatened from certain period with internment in camps for Aryan husbands of Jewish women. The daughters first did not have idea about what happened. To the flat of the David family also came the control to see whether the separation was not done only formally. They found Josef here. He then hired a flat close to their house. The girls suffered a severe blow when their mother received a summons to join a transport to Terezín.

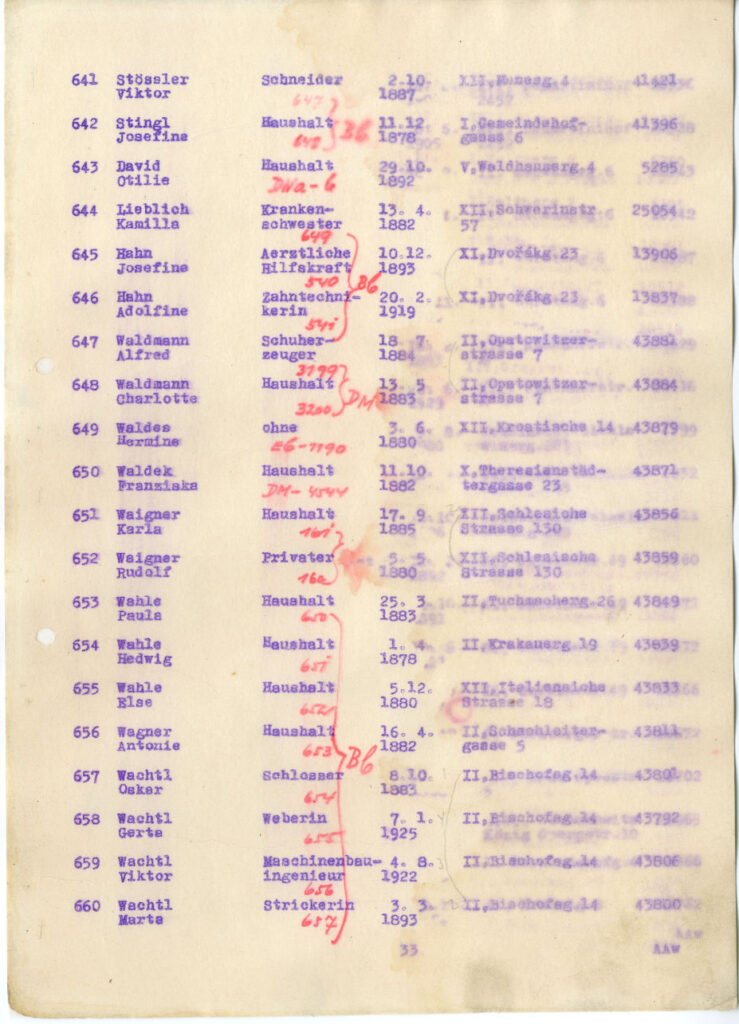

Ottla left for the Terezín Ghetto on August 3, 1942 in a transport marked AAw from Prague. Her daughters helped her pack her things and accompanied her to the assembly point in the area of the former Radiotrh near the Trade Fair Palace in Prague, where they saw her for the last time.

Ottla worked as a ‟Betreuerˮ (caregiver) in one of the boys’ homes in the Ghetto, possibly in L 417 or in another facility. There is a memorial plaque with her name in the courtyard of the Terezín Children’s Park. She was in charge of younger boys aged about 8 years. She used to send her daughters letters from Terezin. When she got a package from her daughters, she shared the contents with the boys in her care (candies, lemons) and also with the people who gave her a parcel permit, because they had no one to send them parcels themselves.

At that time, Ottla’s daughter Věra lived with her boyfriend Karel Projsa. Karel Projsa had previously courted Ottla, who was 20 years his senior, for the same reason. He was a friend of Věra, possibly from the time of her short studies at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University. He himself studied Czech and history in the 1930s. He belonged to a group of Prague avant-garde writers associated with the surrealist movement and structuralism. Karel Projsa helped Věra with the preparation of packages not only for her mother in Terezín, but also for her aunts Elli and Valli and their families in the ghetto in Łódź (they had been there since October 1941). However, the aunts in Łódź never sent any confirmation that they had actually received the packages.

In July 1943, on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of Franz Kafka’s birth, Norbert Fried organized a lecture dedicated to the writer in the Terezín Ghetto. This was Fried’s first ever public lecture in Terezín. He spoke about Kafka, who was not yet widely known, and also read translations from his short stories. Ottla was also invited to the lecture and attended. Since Norbert Fried wanted to learn more about Kafka, he used to see Ottla’s daughters in Prague. In Terezín he arranged a meeting with Ottla, for which he carefully prepared a list of questions. However, that meeting was cancelled due to unforeseen circumstances.

On the morning of August 24, 1943, a group of 1,200 children arrived in Terezín from the Bialystok Ghetto. A revolt had broken out in that camp a few days earlier. The parents and older siblings of the children brought to the Terezín Ghetto had been shot. The Bialystok children were placed in new wooden barracks behind the Terezín fortifications in an area called Crete. The barracks were surrounded by barbed wire to prevent any contact between the children and the Ghetto inmates. The children were cared for by 53 nurses and doctors. Upon arrival, the sick children were immediately separated from the others and placed in strict isolation in the Sokol building.

Ottla volunteered as a nurse for the Bialystok children. At this time, she succeeded in secretly setting up more regular contact with her daughters Věra and Helena through a gendarme. The man, whose name she did not even know, took her letters out of the Ghetto and put them into the mailbox in the village of Hrobce near Roudnice. He even went to Prague several times and personally delivered Ottla’s message to her daughters. In one letter, Ottla wrote to the girls that she was leaving with these children for Switzerland or Sweden. In reality the transport left for the occupied Poland. That was the last time when Norbert Fried saw Ottla, it was over the barrier separating the children’s quarantine from the Ghetto. He asked her whether she would be going to Switzerland or Sweden with her children. She just shrugged her shoulders almost mischievously. Perhaps she believed it herself.

Early in the morning on October 5, 1943, transport codenamed Dn/a with 53 guides (including Ottilie Davidová) and transport Dn/b with 1,196 Bialostok children were dispatched from Terezín under the double designation. It was not heading for freedom, but for the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. Neither Věra nor Helenka received any more letters from their mother. The lives of the Bialystok children, their caretakers and doctors ended in the gas chambers on October 7, 1943. Their dead bodies were burned in a nearby field.

When World War II ended, Věra would often venture to the Wilson Station in Prague to await her mother’s return. She and Helena, who used to stand in front of their house, looked forward in vain to the day when their mother would come back.

Sylvie Holubová

Sources:

https://vltava.rozhlas.cz/petr-balajka-ottla-zivotopisna-hra-o-nejblizsi-sestre-franze-kafky-s-tatjanou-5027934 https://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otilie_Davidov%C3%A1

Balajka, Petr: Ottla. Franz Kafka Publishing, Prague 2018 (in Czech).

Taussig, Pavel: Neznámí hrdinové (Unknown Heroes). Pohnuté osudy (Grim Fates). Czech Television and Albatros Media a. s., Prague 2013 (in Czech).

Wagenbach, Klaus: Franz Kafka. Mladá fronta, Prague 1993 (in Czech).

Frýd, Norbert: Lahvová pošta (Bottle Post). Československý spisovatel, Prague 1971 (in Czech).

https://sfi.usc.edu/video/iwalkcz08-balicky https://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriela_Hermannov%C3%A1 https://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valli_Kafkov%C3%A1#:~:text=Valli%20(Valerie)%20Kafka%2C%20provdan%C3%A1%20Valli,pr%C3%A1vn%C3%ADka%20Franze%20Kafky.%20%5B6%20 % %5D