(review of David Fligg´s book)

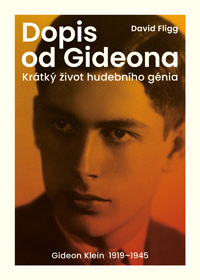

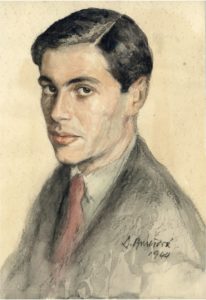

The birth centenary of Gideon Klein, a gifted pianist and composer but also a man of truly versatile cultural interests, was marked in December 2019. His young life ended in the machinery of what the Nazis called “The Final Solution of the Jewish Question” in the Fürstengrube concentration camp in January 1945. On this occasion, the P3K Publishers published a Czech translation of Klein´s biography, written by the British musicologist David Fligg and called Letter to Gideon (with the subtitle – Short Life of a Musical Genius). Let us add that this is the second book dealing with the life and work of this artist to be published. The first one, put out back in 1996 and called Gideon Klein – Torso of Life and Work, was written by Milan Slavický.

David Fligg set himself the task of writing a book of biography in the classical style, examining Klein´s Jewish and Moravian roots, proceeding chronologically in the individual chapters from his birth to his violent death. He also applies himself to the subsequent fate of the composer´s works shortly after the end of World War II. The biographer also follows the life story of Klein´s sister and also pianist Líza. The gist of the book´s benefit lies in the factual description of the life of the members of the Klein family and its history. As a musicologist he analyzes the composer´s preserved works, which makes the book particularly important for the musical science.

However, David Fligg´s book is limited by his unfamiliarity with the Czech language and the ensuing failure to make use (as is evident from a quick look at the list of used literature and notes) of a greater amount of generally available works in Czech on the Terezín Ghetto, and especially sources portraying the Ghetto´s musical and cultural life. This probably caused some factual inaccuracies readers may come across in the book. For instance, there are inconsistencies in the description of the play Ester, accompanied by Karel Reiner´s music and rehearsed in the Ghetto, or the information who really rehearsed the children´s opera Brundibár still before deportation to Terezín. As a matter of fact it was Rudolf Freudenfeld, son of the director of Prague´s Jewish orphanage of the same name, and not Adolf Hoffmeister. Unfortunately, those two factual inaccuracies are not isolated in the reviewed book; it is highly likely that they did not result solely from the author´s failure to use the available literature in Czech, but also from his method of treating testimonies of eye witnesses whose values lie in absolutely different domains than those described by the author.

It is a pity that David Fligg as a musicologist does not examine in his book the recordings of Klein´s works revived after his death. Also, the biographer failed to attach a list of composer´s works, even though such a practice is quite standard in books of this category.

In spite of these objections the author has managed to present vividly the life story of his protagonist in Terezín and also in other places of his imprisonment, aspiring and succeeding to paint a psychologically comprehensive and empathetic picture of Klein´s life and works.

Pavel Straka