Bohumila Havránková, née Picková, was born into a Czech-speaking family in Liberec on November 17, 1927. Her mother, a trained dressmaker, stayed at home, while her father was a retail and wholesale trader in textile. While mother was a non-practicing Catholic, father – as a member of the Jewish community –had both his daughters entered, after their birth, in the Jewish register of births.

In her native Liberec Bohunka, together with her parents and her sister Johana, two years her senior (at home she was called Hanka or Jóha), was involved in the local Czech social life (as a member of the Sokol sports union and as a hiker) and attended a primary school with Czech as the language of tuition. In the autumn of 1938 she became – for a few days – a high school student.

The events following the ”Munich Agreement“ and the related upsurge in aggressiveness displayed by the Heinlein supporters in the Czechoslovak border regions forced the Pick family to leave Liberec and move to Prague – Karlín. Her father acquired a warehouse for his former wholesale business in Prague and the whole family found temporary dwelling in a single office. They shared the unhappy fate of other refugees, a plight that was not received by Prague inhabitants very favorably. Bohumila started to attend high school in Karlín where she was also confronted with various displays of anti-Semitism. She was keen to resume her sports activities in the Sokol organization also in Prague but her classmates doubted that she, as a Jewess, would be allowed to join the local Sokol group. She experienced similar enmity in the behavior of some the other tenants in a house at the border of the Prague districts of Žižkov and Vinohrady where her whole family later found accommodation.

The anti-Jewish regulations, which had already been in place in the country, bore down on the Pick family too. Bohunka had to leave her high school. She became a furrier apprentice but, fortunately for her, only for a brief period of time as she heartily disliked the job. While delivering finished goods to a customer she had lost part of the consignment and was fired. Then she started attending various educational courses held in private apartments, and she eventually passed her final exams in Prague´s Jewish School.

At the time when the duty of the Jews to wear a star of David on their clothing came into force her mother thought that the so-called half-breeds need not wear the star and kept persuading her daughters that she was right. On the very first day, a very unpleasant incident happened to Bohunka: as she was walking through Prague with her friends, who had their stars of David sewn on their clothes, one woman passing by accosted her, calling her names and asking if she wasn’t ashamed of herself hobnobbing with Jewish girls. After that incident Bohunka asked her mother to sew a star on her own clothes too. Later on she expressed her wish to go to the cinema even though it was already impossible for her. Her cousin tried to get her into the cinema and she almost succeeded but a cinema attendant refused to let her in anyway. Bohunka was afraid he had found out that she was hiding her star and would be punished. It came out in the end that the particular film was X-rated.

In the period prior to her transport to the Terezín Ghetto Bohumila spent her happiest moments with her friends in the grounds of the Czech Jewish sports club Hagibor. Vojtěch Feuerstein, popularly known as Faji, member of the left-wing resistance movement, served there as an educator of the girls. He was a lodestar not only for Bohumila but also all the other girls. For his resistance activities Vojtěch Feuerstein was later executed in the Mauthausen concentration camp.

On March 6, 1943 Bohunka and her sister left Prague in a transport code-named Cv on their way to the Ghetto in Terezín. Their father was protected from transports thanks to his life in a mixed marriage and, furthermore, at the end of the war, he fell seriously ill and was sent to a hospital.

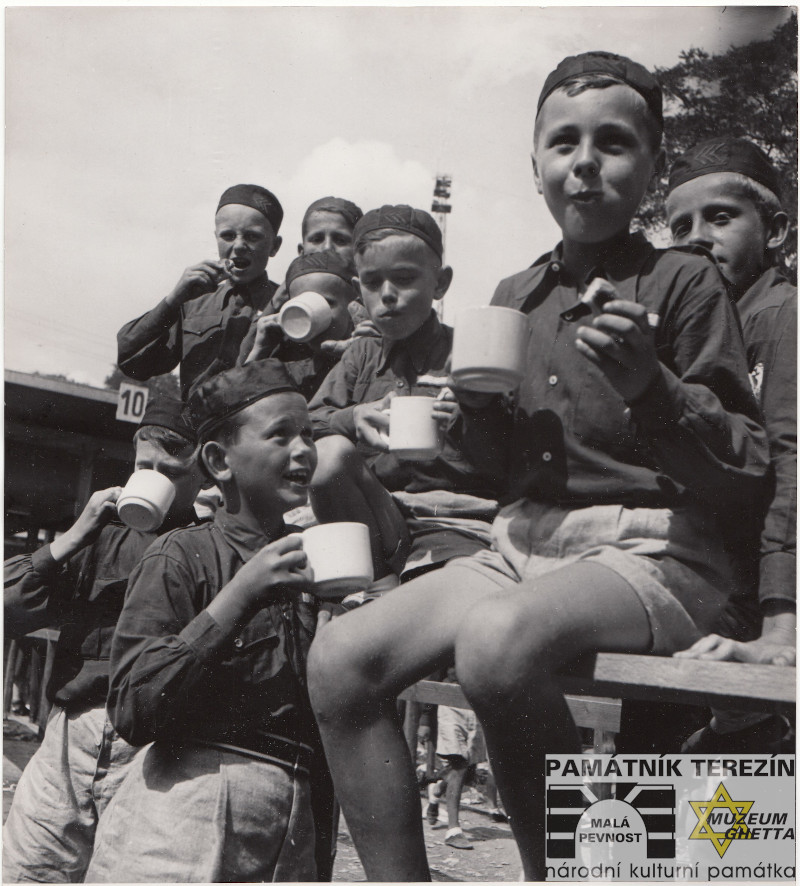

Bohunka´s memories of the time spent in the Ghetto are highly varied. Her worse recollections harked back to the Terezín latrines, forced presence during punishment of a fellow inmate by other prisoners, her pneumonia etc. However, there were many other more positive moments which eventually helped her survive the harsh life in Terezín – farm work (growing tomatoes), feeding silkworms, stay in the girls´ home L 410 etc. Bohunka and her friend also found in the Ghetto a teacher of Russian whom they paid for the lessons with bread. His quality of language teaching was so exceptional that after the war Bohunka was the best student of Russian in her class. An unforgettable experience for her in the Ghetto was meeting and working with Karel Berman, a later star of the opera of Prague´s National Theater, whom the girls joined in Terezín in singing such works as Moravian Duets or the operas In the Well, The Bartered Bride and Rusalka.

A view of Prague, Bohumila´s postwar photographic work. Private archive of Bohumila Havránková

As part of her job she also took pictures at the Sokol Festival in 1948. Private archive of Bohumila Havránková

Before the end of the war Bohunka, together with her friend Lída, managed to leave Terezín and took a train from Bohušovice to Prague, where they experienced the atmosphere of Prague uprising and the dramatic moments of the war´s end. They were even detained by a German soldier but succeeded to come out unscathed. Bohumila eventually got back to her home and finally rang the doorbell. Only her father was in at that time and his first words of “welcome “ after her ”premature return from the Ghetto“ were somewhat unexpected, as he greeted his daughter saying: ”Well, you could have stayed there for a couple of more days!“.

While in Terezín Bohunka got hold of a copy of an avant-garde magazine with photographs which appealed to her to such an extent that, already there and then, she decided to become a photographer after her return home. And that really happened. After the war she graduated from a vocational school of graphic arts specializing in photography and began working as a reporter for the daily newspaper Rudé právo. However, after her maternity leave she could no longer return to this work but photography proved to be her lifelong hobby.

St