There were numerous personalities associated with the interwar avant-garde culture in Czechoslovakia among the Terezín Ghetto inmates. These included, for example, architect, costume and stage designer František Zelenka (who also worked in the Liberated Theater), writer, photographer and later diplomat Norbert Frýd (who cooperated with E.F. Burian´s Déčko Theater), dancer and choreographer Kamila Rosenbaumová (known as Rónová after the war), conductors Karel Ančerl (Liberated Theater) and Rafael Schächter (Déčko Theater) and, last but not least, composer, ethnomusicologist, music critic and organizer of cultural life Karel Reiner.

Karel Reiner was born on June 27, 1910 in the town of Žatec, in a family of Josef Reiner, a music teacher and chief cantor of the local synagogue, a trained opera singer. At his father´s wish, Karel had graduated at a law faculty but never practiced as a lawyer, devoting himself intensely to music. A pupil of Josef Suk, he studied the quarter-tone and sixth-tone scales with Alois Hába, performing with him as a pianist. In 1934 he joined E.F. Burian´s Déčko Theater as a pianist and composer of stage music (e.g. for the dramatization of Mácha´s Máj (May), Pushkin´s Eugene Onegin or V. K. Klicpera´s play Každý něco pro vlast (Everyone Something for the Homeland). At that time, he was in charge of the musical supplement of the modern women´s magazine Eva, where he also published several of his songs. In addition to stage music Reiner also composed modern classical music. Just like his contemporaries Jaroslav Ježek, Ervín Schulhoff and Emil František Burian, he was influenced by jazz, and as a member of the left-wing cultural scene he also composed Soviet-style mass songs.

After the establishment of the Protectorate Karel Reiner worked as an editor of the official press organ of the Prague Jewish community Židovské listy (Jewish Newspaper). For a time, this job protected him and his wife from being assigned to transport to the Terezín Ghetto. By that time, Reiner was banned to publish under his own name. His colleagues, composers Jan Seidel and Alois Hába covered up Reiner´s authorship of a study on harmonization of folk songs in a two-volume publication called Špalíček národních písní a říkadel (Collection of Folk Songs and Nursery Rhymes), which appeared in 1939.However, the postwar re-editionsissued in 1948 and 1957 did feature Reiner´s name. In a similar vein, Reiner´s study Exotická hudba (Exotic Music) in Jan Branberger´s book Dějiny světové hudby (A History of World Music) from 1939 was signed by Alois Hába. Strangely enough, Mirko Očadlík´s study in the same book contained a description of the works of Karel Reiner.

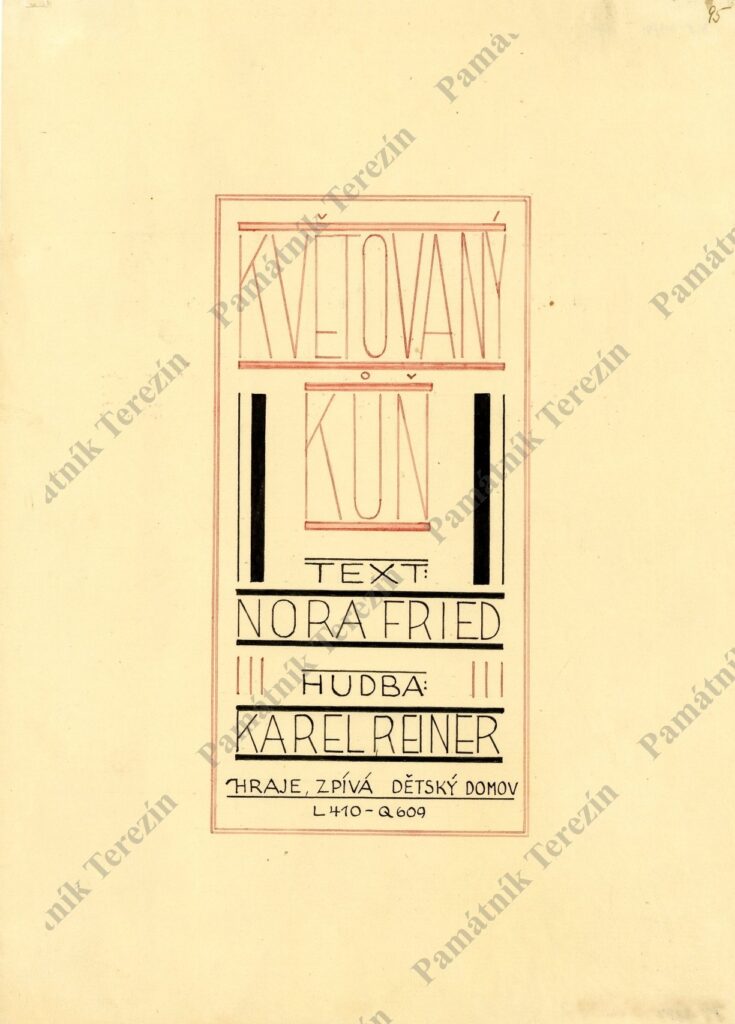

In the fall of 1942, Reiner set to music a cycle of lyrical poems by Norbert Frýd called Květovaný kůň (Flowery Horse) and written in May of that year. This was an attempt to offer Jewish children in orphanages an alternative musical and literary method of learning the alphabet at a time when Jewish children were banned to go to school. The cycle was originally composed for a children´s choir and piano, but due to the situation in the Protectorate the singing parts were performed by Norbert Frýd, author of the lyrics, with Reiner´s piano accompaniment. After their internment in Terezín the authors of the cycle rehearsed the program with children in the Ghetto. Several renowned Czech music ensembles, such as the Kühn Children´s Choir, Severáček or the Brno Children´s Choir included some of the songs from the cycle into their own repertoires in the postwar period. For its part, the Disman Radio Children´s Ensemble staged the entire cycle in its recited version. But it was the Brno Children´s Choir, led by choir master Valerie Maťašová, that recently came closest to Reiner´s original musical concept; the ensemble performed almost the entire cycle in the Terezín Memorial on several occasions, during the ceremony of awarding prizes to winners of the Memorial´s art competitions for children.

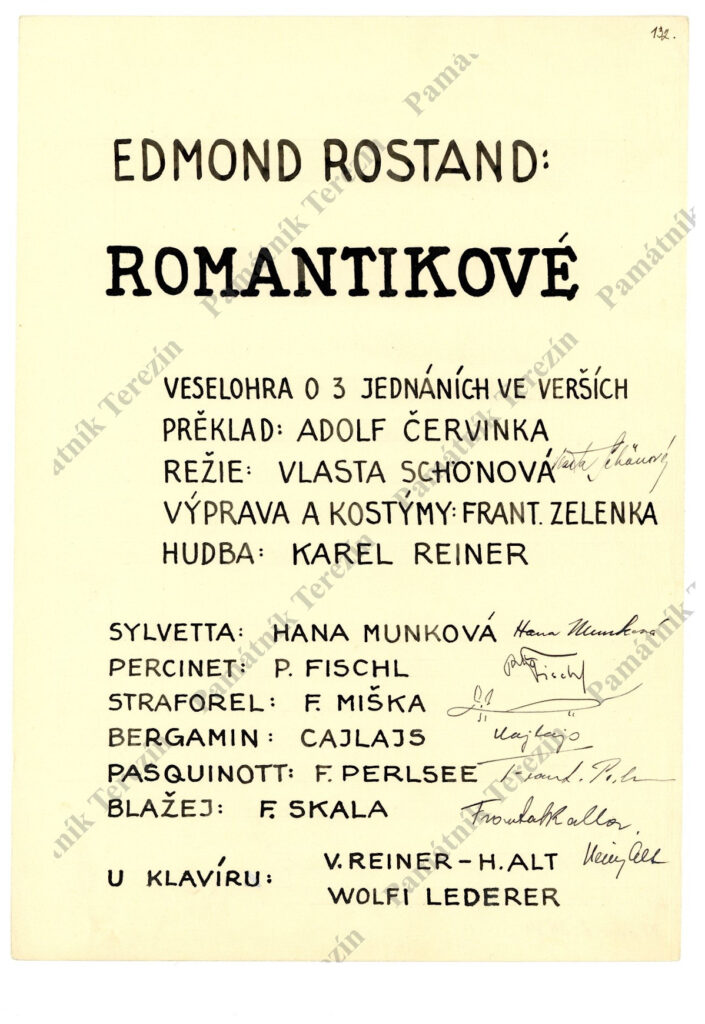

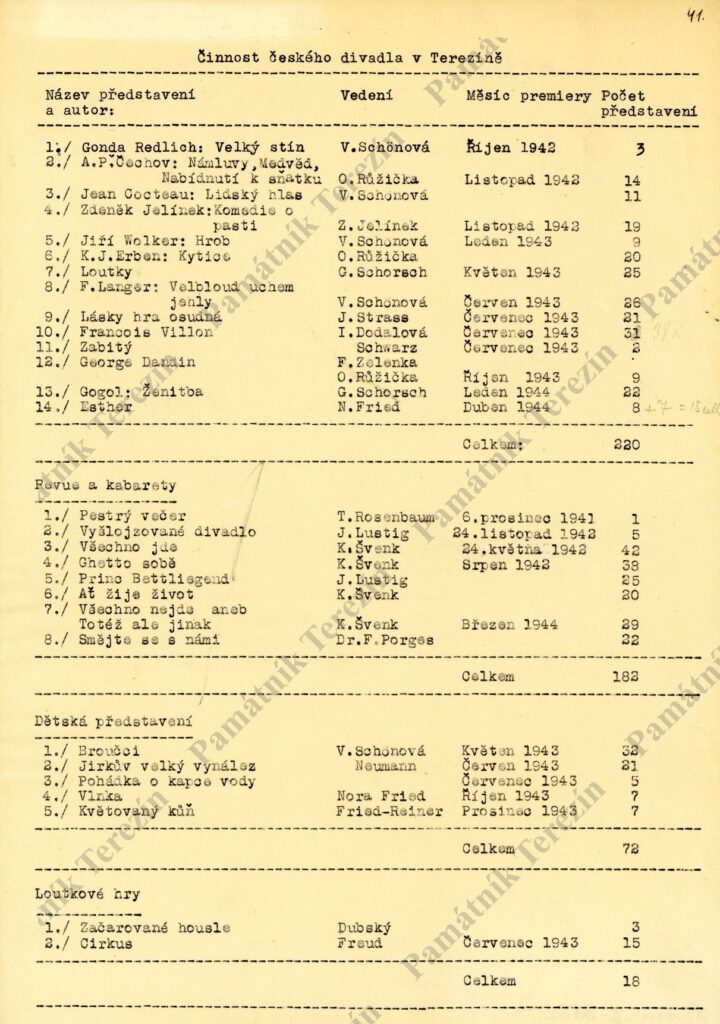

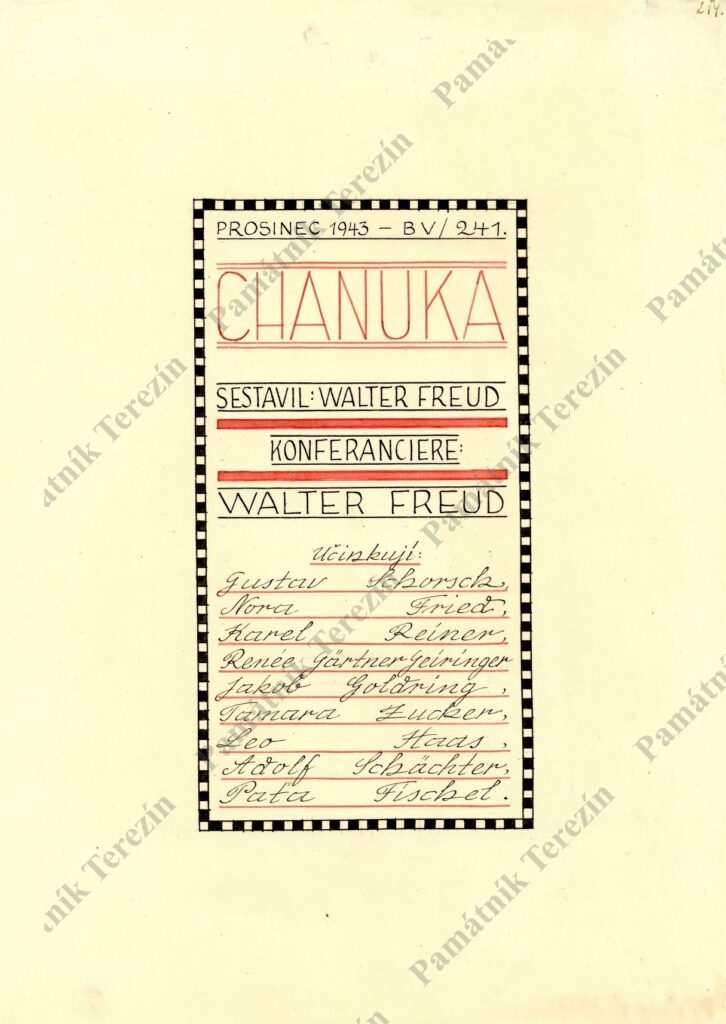

The Reiners were deported to the Terezín Ghetto by transport De on July 5, 1943. Karel Reiner worked as a youth educator (Betreuer) in building Q 609, where he staged with 13- and 14-year old boys Karel Jaromír Erben´s fairy tales Král Tchoř (King Polecat) and Otesánek (cf. Cookie Monster) in a voice band arrangement he had already prepared for E.F. Burian´s Déčko Theater before the war. Reiner also composed music for Edmond Rostand´s play Romantics and Strakonický dudák (The Strakonice Bagpiper) by Josef Kajetán Tyl. These works, just as some other compositions Reiner wrote in the Ghetto (e.g. cycle of choral songs accompanied by a string quartet in a sixth-tone scale to words by Christian Morgenstern) have not been preserved. Reiner´s only extant opus known to have been composed in Terezín is his stage music accompanying an old Czech play on Biblical theme called Esther. This staging had been originally planned for the Déčko Theater by E. F. Burian himself but it never materialized. The text of the play together with director´s notes had been brought to Terezín by Norbert Frýd who then directed its performance. It was not surprising that the story about an uprising against the genocide of ancient Jews planned by Hamman, a high-ranking official of the Persian Empire, resonated in the Ghetto.

Musicologist Milan Kuna and Reiner´s wife Hana, assisted by the actors (Jan Fischer, Hana Pravdová, Zdena Fantlová), who had performed in the wartime staging of Esther in the Ghetto and who remembered the melodies, reconstructed the tunes of the songs from that staging.

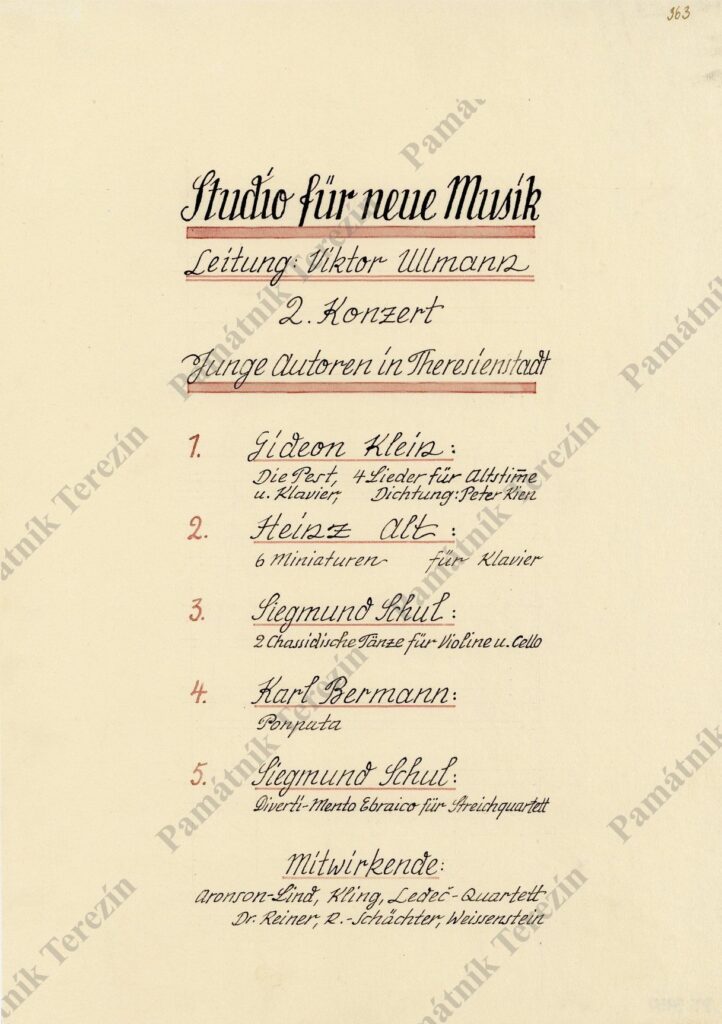

While in Terezín, Reiner gave piano concerts, albeit to a limited extent, playing compositions by Vítězslav Novák or Josef Suk. In March1944, he accompanied Karel Berman´s performance of Bedřich Smetana´s cantata Česká píseň (Czech Song) led by Rafael Schächter´s choir, and some time earlier, on February 19, 1944, Reiner accompanied singer Hedda Grabová–Kernmayrová in a program of modern Czech music (Josef Suk, Vítězslav Novák, Karel Boleslav Jirák, Leoš Janáček). He also partnered conductor Karel Fischer in a performance of Mendelsohn´s oratorio Elijah.

In the Terezín Ghetto, Reiner joined the local communist resistance group, being active in an underground system known as threes; he also maintained contact with František Graus, future medieval historian, and artist and art therapist Friedl Dicker–Brandeis.

Karel Reiner was deported from Terezín to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp on September 28, 1944. After several days in the death camp he was transferred to the Kaufering camp in Bavaria where he contracted spotted fever. He was cured by two doctors who knew Reiner as a prewar member of the Burian Theater in Prague. One of them, Emil Katz–Klíma, then kept Reiner as his scribe in the camp hospital. Following the hardships he had suffered on a death march and after finishing his quarantine he came back to Prague on May 22, 1945 where he was reunited with his wife Hana.

After the war, Reiner was a music publicist writing for such magazines as Kulturní politika (Cultural Policy), Svobodné Československo (Free Czechoslovakia) and was employed in several musical associations. During the 1950s he worked for a long time as the chief methodologist of the Central House of People´s Creative Art, specializing in choral singing. Together with Alois Hába he founded the May 5th Opera. Starting in 1961 he became a free-lance music composer, while holding various positions in music organizations and associations.

Out of Reiner´s numerous postwar works (instrumental music, mass songs, adaptations of folk songs, music to documentaries, compositions for children etc.) worth singling out is his composition reflecting his imprisonment in Terezín and his educational activities. This was primarily created for a poetic documentary called Butterflies Do Not Live Here and directed by Mirko Bernát in 1958. The documentary portrays the world of the children imprisoned in Terezín as well as the then opened Memorial of Protectorate Victims of the Holocaust unveiled in the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague. Two years later Reiner composed an independent symphonic work based on the music from that documentary.

Karel Reiner, who died on October 17, 1979, is buried in Prague´s Vinohrady Cemetery together with his wife Hana (see article in Newsletter No. 3/2021) and their daughters Michaela and Kateřina who were known to promote the musical heritage of their father especially in the association known as Přítomnost, spolek pro soudobou hudbu (Present, a union for contemporary music). As a matter of record, Reiner took a prominent role in the activities of the union during the prewar and early postwar years.

Pavel Straka