(28. 5. 1889 – 28. 10. 1944)

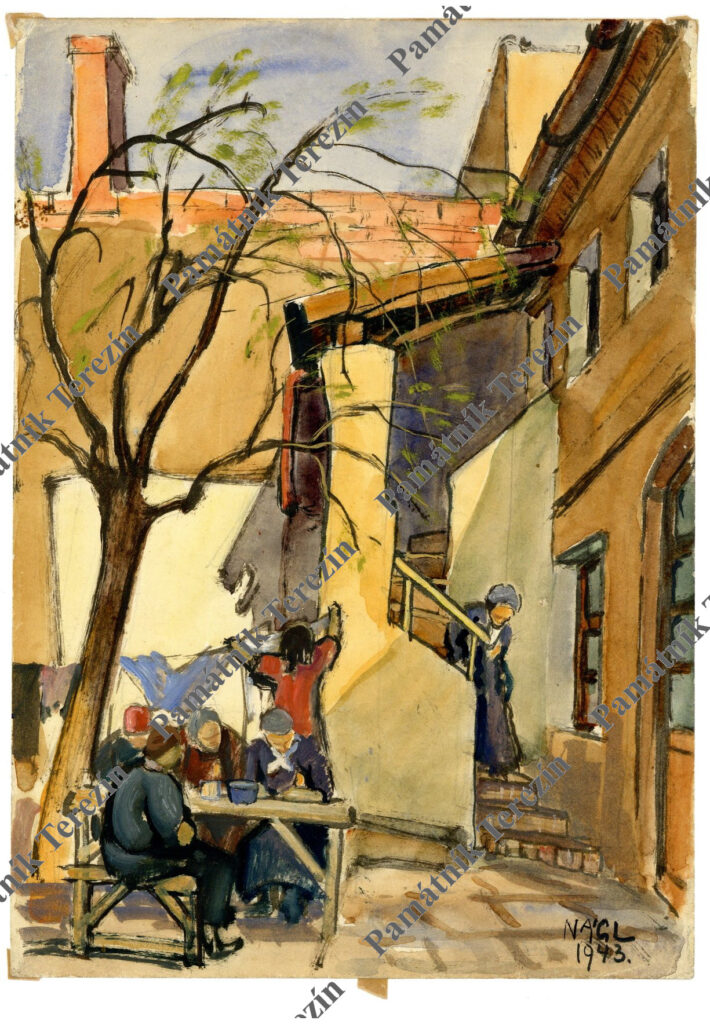

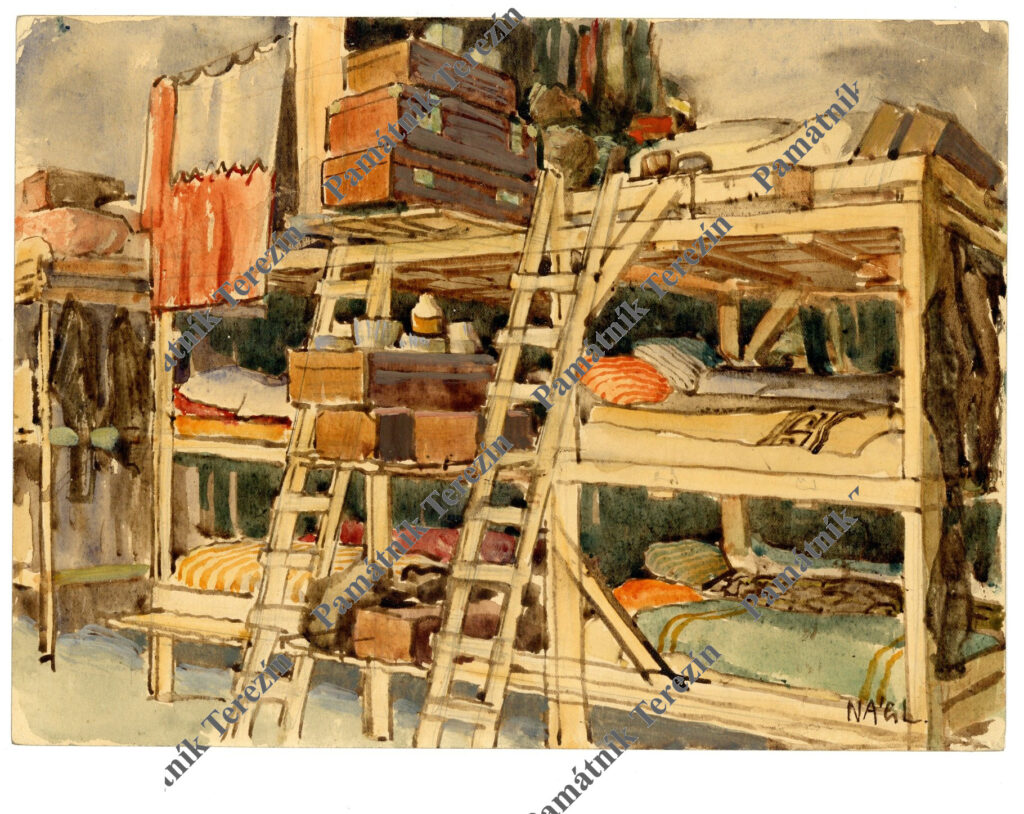

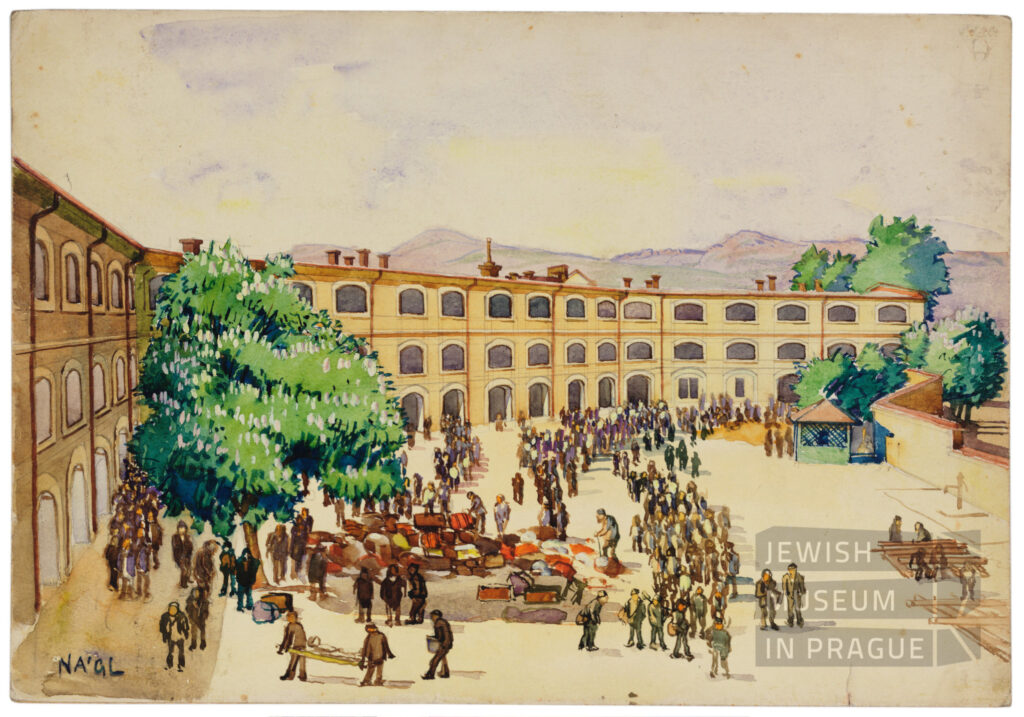

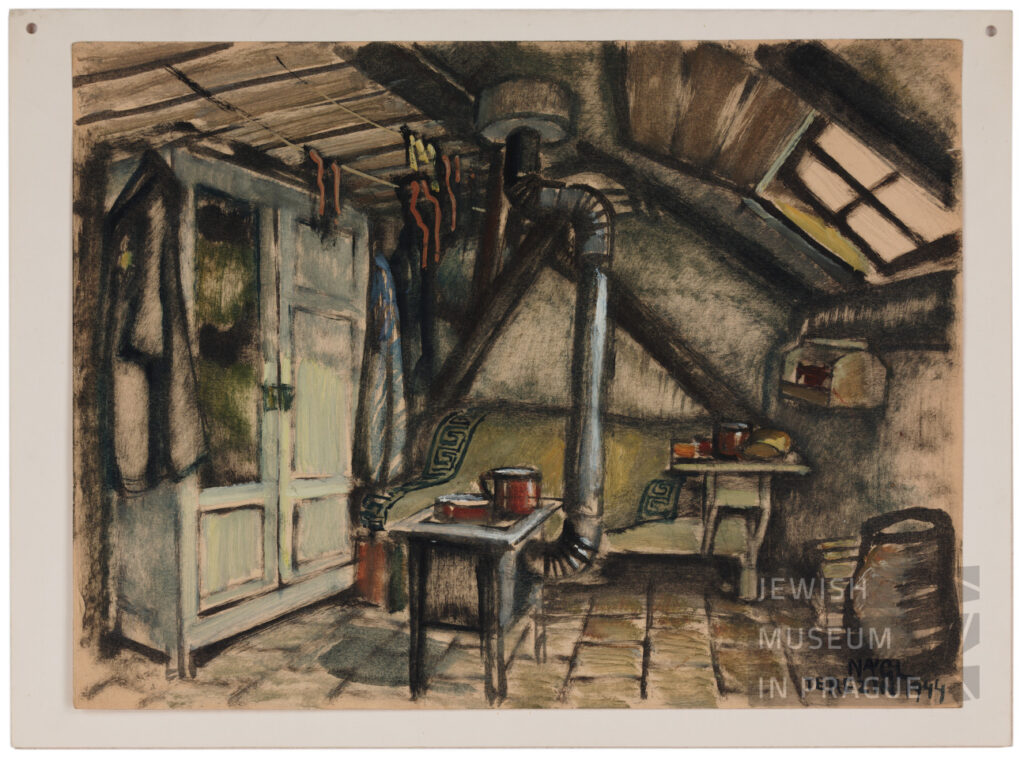

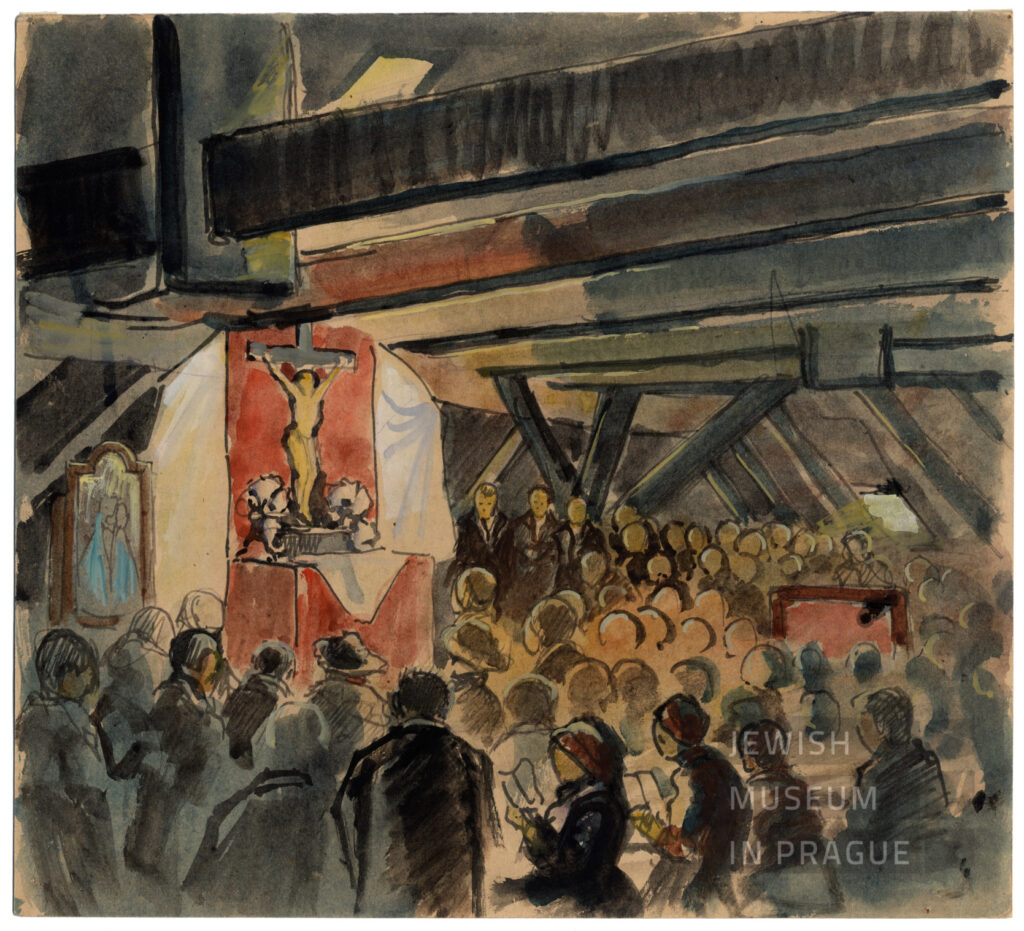

Walking through the first floor of the Magdeburg Barracks, the section housing the Terezín Memorial’s exhibition dedicated to the fine arts created in the Terezín Ghetto between 1941 and 1945, visitors will hardly miss a set of colorful pictures capturing the Terezín Ghetto barracks and dormitories. Thanks to their subject matter and colorfulness, they help the attentive observer understand the hardship of life the inmates had to face. Their author is František Mořic Nágl, a Ghetto prisoner and painter from the Jihlava region, from the village of Kostelní Myslová.

His ancestors had lived in the Highlands since the late 18th century. The Nágls were among the wealthiest families in the village – they owned a mill, land, and a large estate. Mořic and his two sisters attended a single-class elementary school there, and he went on to study at a grammar school in Telč. At the age of fifteen, he enrolled in the Prague Imperial and Royal School of Applied Arts, where he began his studies in 1905. Later he continued at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, in the studio of Professor Hanuš Schwaiger. Mořic finished his studies and returned home in 1912.

The First World War had a negative impact also on the life of Mořic Nágl. The painter had to be drafted and enlisted in the army. During the fighting, he was wounded in the right shoulder. Doctors operated on his hand, saved it and Nágl was able to continue painting. However, he did not return to the front line.

Mořic got married in 1920. His bride was Vlasta Nettlová, eleven years his junior. Like the Nágls, the Nettl family was of Jewish origin. At that time, Mořic, as the only son, took over the administration of the estate in Kostelní Myslová and the young couple also lived in the village. The family gradually grew, with the birth of their first child: daughter Věra was born in the summer of 1921, followed by son Miloslav in the fall of 1922. Mořic Nágl’s wife Vlasta had an artistic inclination, particularly in the realm of music, and tended more towards city life.

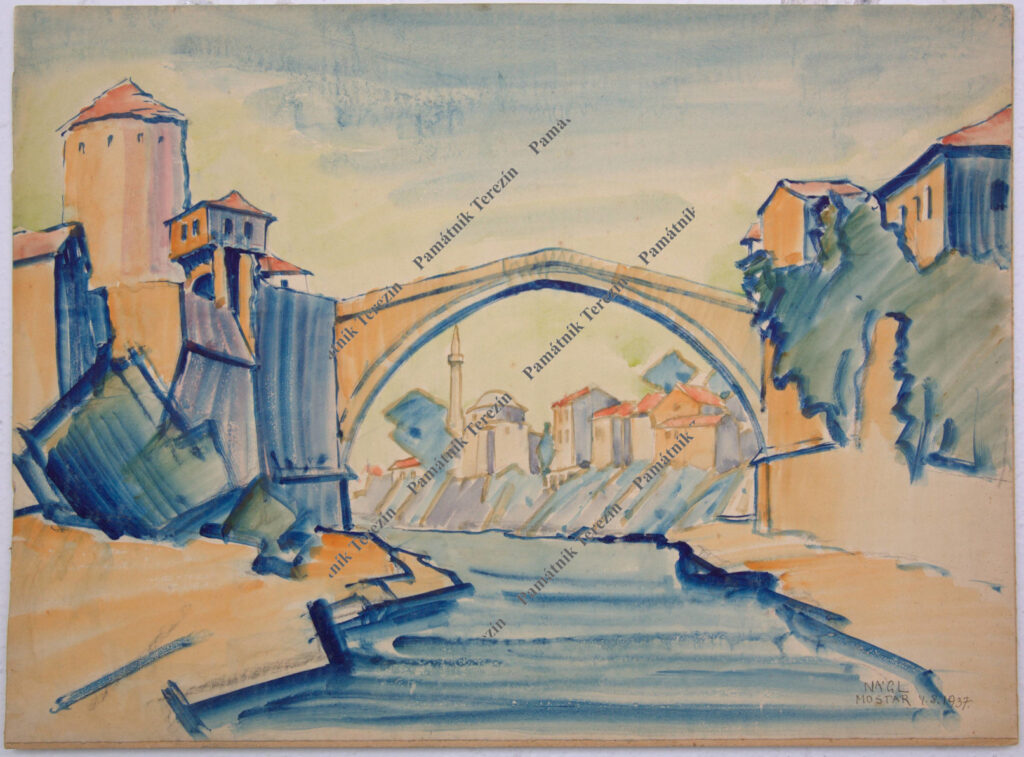

Nágl was assisted in the running of the family farm by an estate manager and the painter was able to devote himself to his art. He captured not only his surroundings and life in the village but also the streets of Telč, Jihlava and the Highlands region in general. The family used to go on holiday to the Adriatic, where he created a large number of works with local seaside motifs.

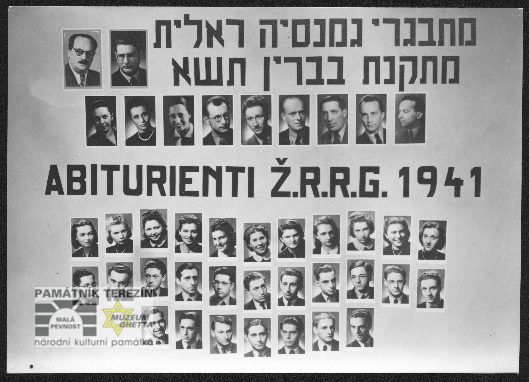

The Nágls also bought a house in Telč, where both children studied at a grammar school. With the occupation and the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the family, as well as the rest of the population of Jewish origin, was affected by the Nazi anti-Jewish regulations. The children had to leave school in Telč, Věrka managed to finish her studies at the Jewish grammar school in Brno. Her picture can be found on the group photo of her graduating class at that school.

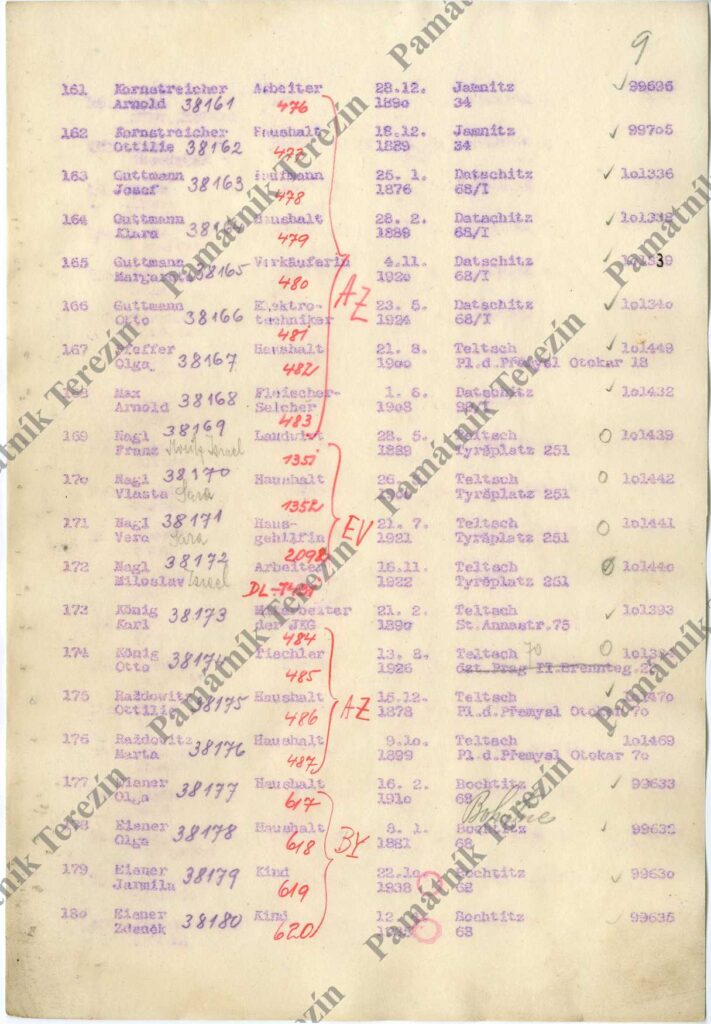

In May 1942, the whole family was summoned to a transport to the Terezín Ghetto. The transport was marked Aw and left the assembly point in Třebíč on May 22, 1942. Its transport list provides information about individual family members. František Nágl is listed as a farmer, Vlasta as a housewife, her twenty-one-year-old daughter Věra as a domestic help, and her brother Miloslav, who was a year younger, as a worker. Their last place of residence was a house on Tyrš Square in Telč, No. 251.

We know very little about Mořic Nágl’s life in the Ghetto. However, several dozen of his works of art made in Terezín tell us about his life in the camp. His paintings are descriptive and almost documentary in nature, and today they help us learn about life in the Ghetto and its environment in general. They show the mass prison dormitories, the small cubby holes, and the everyday life in the Terezín yards and in the streets of the Ghetto. We are also offered a view of Terezín and its surroundings from the ramparts. Every detail is executed with meticulous descriptiveness. The paintings are also evidence of his creative drive that did not leave Mořic Nágl even in the Ghetto, and they are proof of his movements around the camp to capture as much of local life as possible.

Unfortunately, not even the Nágl family was spared the fate of many thousands of deportees from the Ghetto to the East. Mořic’s son Miloš was included in a transport already in September 1943. This was the transport codenamed Dl heading to the so-called Terezín family camp in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where Miloš perished. Mořic and Vlasta Nágl, bearing transport numbers Ev 1351 and Ev 1352, respectively, left the Ghetto for the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp on the last fall transport in 1944. Their daughter Věra was in the same transport, with the high transport number Ev 2038. All three were murdered in the East.

After the war, several dozen of Nágl’s paintings were discovered in the attic of one of the houses in Terezín. In 1951, the Jewish Religious Community in Prague, the Czechoslovak Committee of Peace Defenders and the Third Group of the Union of Czechoslovak Fine Artists Mánes staged an exhibition of his paintings in the Mánes exhibition hall in Prague. They are regularly displayed at exhibitions dealing with the history of the Terezín Ghetto to this day.

Naděžda Seifertová

Literature and sources:

Vojtěch BLODIG – Kurt Jiří KOTOUČ – Marie Rút KŘÍŽKOVÁ – Milan KUNA – Jan MUNK – Arno PAŘÍK – Eva ŠORMOVÁ – Ludvík VÁCLAVEK, Art Against Death, Permanent exhibitions of the Terezín Memorial in the former Magdeburg Barracks, OSWALD Publishing House, 2002, pp. 136 – 139.

Oldřich KLOBAS, Malíř neumírá (Painter Never Dies), Brno 2020 (in Czech).

Testimony of Ella Machová, USC Shoah Foundation – Visual History Archive. Interview code 8785. Date of interview: Dec. 21, 1995.