(When the Documents talk…)

Thanks to the preserved sources on its construction, on previous owners, its intended or actual use, every house in Terezín, whether built for military or civilian purposes, could serve as a piece into the mosaic of the town´s history. Take, for instance, the diverse and exceptionally rich file of documents relating to the burgher house No. 145, situated in what is today Tyršova Street, which clearly reflects and exemplifies not only the social changes in the Czech lands but also Terezín´s entire historical developments. A large amount of these archival documents are kept primarily in the State District Archive Litoměřice based in Lovosice, and in the private archive of Mr. Vratislav Král, erstwhile owner of the house. The relevant documents were collected and analyzed by Markéta Stará, an undergraduate of the Technical University in Liberec, with this article drawing heavily on her bachelor´s thesis.

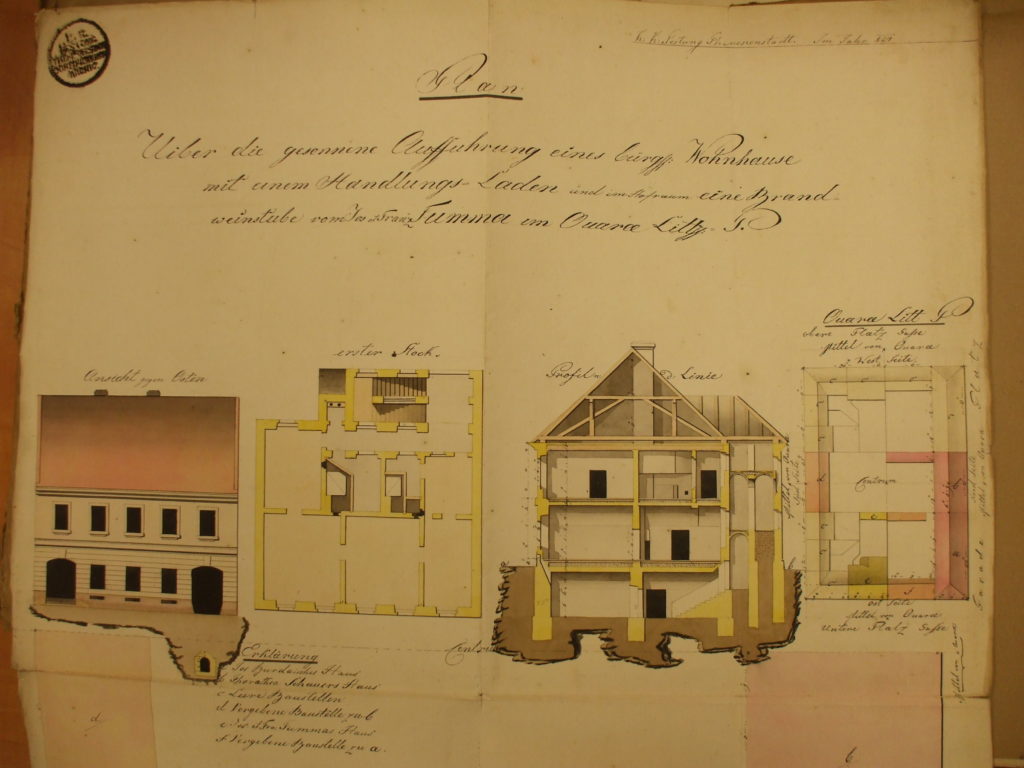

The first document proving the existence of the house is its construction blueprint, dated April 8, 1824. Drawn up in accordance with the existing building regulations and the terms set forth by the Patent of Settlement issued by Emperor Joseph II in 1782, the blueprint was duly approved by the Engineering Directorate in Terezín. The building document bears, among other data, the names of Josef and Franz Tumm, the house owners, and reveals their intention to build an apartment house with a store on its ground floor, and a liquor store or a “dive” in its yard. The building´s subsequent construction is documented by a map of Terezín from 1825, registering the house as a project under construction.

The second half of the 1820s figures as a period of Terezín´s marked construction and demographic upsurge. A salient feature of this period was close synergy of the civilian and military components of the town´s development, while various crafts, trading and catering services constituted a major source of livelihood of the local civilian population. It may be assumed that the Tumm family had also benefited from the potential offered by the local military garrison since they had another burgher house, No. 146, built in the close vicinity of their original seat in the 1860s. Later documents from the early 20th century imply that the Tumms also leased their real estate, including the “dive” in house No. 145. The census data gathered in February 1921 may be interpreted as a confirmation of the adequate and multi-faceted entrepreneurial environment in the town as well as a reflection of the great rush for accommodation coming, among others, from the members of the local military garrison. According to the census data, five apartments in house No. 145 were inhabited by as many as 16 people, including Czechoslovak army officers. Furthermore, this particular source also showed that 13 out of the 16 tenants professed their Czech nationality, while one of them ran a grocery, probably situated on the ground floor.

In the spring of 1921, Antonín and Marie Šlechta bought the house from the original owners. Their intentions may be deduced from a written notification to the Municipal Authority in Terezín on March 28, 1921, in which an authorized architect announced building adaptations in the yard of the house for the purpose of converting it into additional flats. The probable intent of the new owners to lease the converted premises seems to correspond with A. Šlechta´s documented profession as an owner of real estate and of a butcher´s shop in the nearby town of Budyně n. Ohří but also fits in with the housing shortage, a typical trouble besetting Terezín during the first years of the Czechoslovak Republic. The preserved documents show that the conversion really got off the ground but also reveal the subsequently denied permission to use the premises for accommodation, delayed approval of the building etc. The question remains whether and to what extent these official complications had actually led the Šlechtas to the decision to sell their house in February 1927 to new owners who, however, sold half of the house to Josef Král already in September of that year. As early as in October 1927, Josef Král and his wife Emilie owned the whole object.

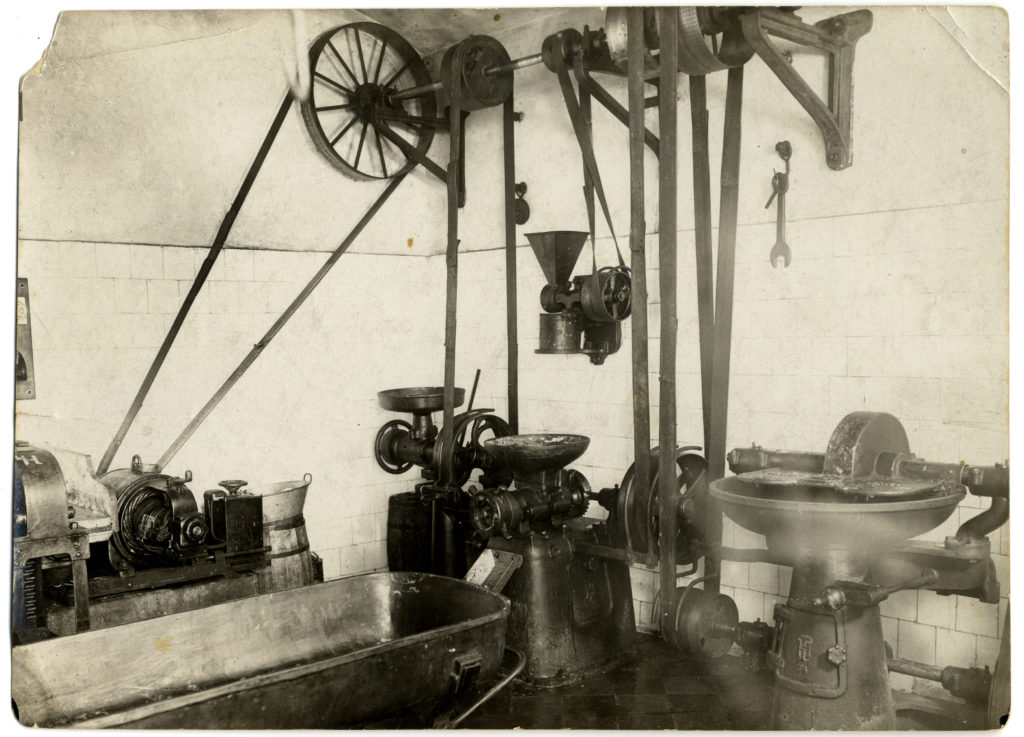

The change of house owners was accompanied by striking structural changes stemming from Josef Král´s business plans. Mr. and Mrs. Král changed the front of the house, building a butcher´s shop on the ground floor and a butcher´s workshop in the yard. It is impossible to prove that a laundry room was also opened in the yard, as stated in a notification to the Municipal Council in Terezín and in the attached skeleton sketch from September 1927. The fact is that Josef Král´s butcher´s and meat-merchant business flourished, as corroborated by other structural improvements and adaptations of the house in the early 1930s, including the construction of a garage in the yard for a Praga AN truck owned by Josef Král. This respected Terezín citizen and chairman of the local Union of Butchers and Meat-Merchants died in 1937, with wife Emilie and sons Bohumil and Jiří becoming the owners of the premises. Widowed Emilie ran the well-established butcher´s and meat-vendor´s business and store even at the time when part of Terezín had already been turned into Jewish Ghetto. In view of the approaching deadline for the local population to move out of the town she closed down her business on June 11, 1942. Shortly before then the house changed hands again since the Králs, mother and sons, were forced to conclude a contract of sale on May 28, 1942; they sold the house No. 145 complete with the machinery in the workshop to the Emigration Foundation for Bohemia and Moravia.

This Foundation managed the property confiscated from Protectorate Jews and duly grew to be the sole owner of the premises belonging to Terezín denizens. It was an example of coarse cynicism that the sale of buildings, used from the summer of 1942 to May 1945 as part of the Jewish Ghetto, had, indeed, been financed from the property seized from the new, coerced inhabitants of Terezín.

As a result of the changes of the whole town into the Ghetto, house No. 145 received not only new inhabitants but also a new address, namely L 413. The surviving documents, coming primarily from the archives of the Ghetto´s Jewish Self-administration, shed light on the constantly changing use of the ground floor of the house with its store. For instance, Order of the Day No. 255, issued on November 20, 1942, said that a grocery store was situated in L 413. However, its range of goods changed in the following months since Order of the Day No. 335 from June 23, 1943 mentioned L 413 as housing a store selling second-hand goods where inmates were allowed to buy at prescribed times suitcases, bags and satchels of the first to third quality category. The Ghetto´s total of 14 stores offered prisoners for purchase second-hand goods in various conditions according to which three categories of goods were distinguished. Quality then affected the price of goods, given in the so-called Ghetto crowns in the fall of 1943. This was the camp´s new currency replacing the previous vouchers distributed to the inmates by the Jewish Self-administration as a result of Nazi efforts to promote Terezín´s propaganda image. Inmates´ entitlement to receive goods in a certain quality depended on the color of individual vouchers.

The Internal Administration Department of the Jewish Self-administration, specifically its subdivision: economic facility management, prepared a document giving an overall picture of the floor area of the building L 413, its furnishing and actual occupancy by inmates. According to a list of houses, as of October 1, 1943, L 413 housed seven dormitories with 69 accommodated persons, while 50 prisoners lived in the attic. At that time, the house had three toilets and three water faucets. The list also mentioned the object´s special purpose in a note Koff. & Fleisch (abbreviations for suitcases and butcher´s shop).

That the butcher´s shop was still used for its original purpose was confirmed not only by official documents but also by eyewitness reports by former Ghetto inmate Edgar Krása, who had been occasionally employed in the butcher´s shop between 1942 and 1943. According to his testimony, butchers only worked in L 413, having their dormitories elsewhere. Ghetto inmates were not accommodated on the ground floor but on the upper floor and in the annexes in the yard. The butcher´s shop itself was situated on the ground floor; it processed meat, mostly horse meat, that was destined exclusively for the prison kitchen and prisoners were not allowed to buy it.

In the Ghetto´s organizational structure, the butcher´s shop belonged, in administrative terms, to the provisions section, part of the Economic Department of the Jewish Self-administration. As implied by a document prepared by the Jewish Self-administration in 1945 (without a precise date), there were two stores in the house – one selling suitcases and haberdashery goods, and an ironmonger´s shop, however both out of operation at that time. The same document also specified that a total of seven people worked in the butcher´s shop in 1945, while inmate Benno Spitzer was the person responsible for its operation. The same name is to be found on a hand-written note, part of the private archive of the Král family. Beno (sic!) Spitzer is mentioned on the note as the last foreman in the central butcher´s store. Another interesting piece of information on the note is that all the equipment of the workshop was functional on May 5, 1945.

The prewar owners, Emilie Králová and her sons, moved back to house No. 145 during the first wave of original Terezín inhabitants returning after the war. However, this happened as late as in August 1946 since Terezín had been officially closed to civilian occupancy from the spring of 1946. The wartime existence of the Ghetto was severely reflected in the deplorable state of the local buildings that had to be thoroughly renovated, made habitable again, eventually reverted to their original purpose or given a new purpose. This could not be achieved without considerable financial costs and protracted negotiations not only with the local inhabitants but also with the municipal and district authorities.

Encounter with the same obstacles and red tape were in store for the Král family. The postwar documents mentioned considerable damage to their property, chronicling the course of repairs of the house and their efforts to resume their butcher´s and meat-merchant business, as well as the fact that Josef Král´s original machinery and equipment had been used in the camp´s butcher´s shop during the time of the Ghetto. The plans devised by Jiří Král, son of Emilie and Josef Král, to resume the family business tradition were thwarted by the authorities that failed to issue him a business license in the spring of 1949. Starting in April 1950, Emilie Králová leased the ground-floor premises to the national enterprise Masna Litoměřice which operated its branch manufacturing facility in the house until the fall of 1951. Following events in the 1950s, including the use of the butcher´s shop and the two stores on the ground floor, are not reliably documented due to missing sources. Emilie Králová and her son Jiří with his family lived in the two repaired apartments on the first floor.

The history of the house in the 1960s and the following decades was recounted in his memories by Mr. Vratislav Král, son of Jiří. According to his recollections, from the mid-1960s the house´s commercial premises were utilized by the consumer cooperative Jednota that set up its store in the object. No information about the goods sold in the store is available; it may be added that the store sold textile products during the 1980s and up to the early 1990s when the lease contract with the consumer cooperative was terminated. Following on from there, Vratislav Král started his own business, converted the ground-floor premises into a car-repair service, which closed down after the flood in 2002. In 2012, he had sold the whole building to a new owner who then converted the ground floor into a café called Café Pandur, opened in 2013. With both the name of the café and its furnishings its new owner sought to link up to Terezín´s earlier history, contributing to the current presentation of the town; in addition to the sad wartime stages in its history, Terezín has also been trying hard to show visitors its earlier and happier history. Still, the café had been opened only shortly, as the owner sold the premises again, and the whole house now serves solely for accommodation.

The variety, wide range and quantity of sources tracing the history of house No. 145 make it possible to chronicle some of the stages of its existence in much greater detail, which, however, goes beyond the scope of this article. Generally speaking, the preserved archival documents also support the prevailing trends of historical developments on a society-wide scale, such as the gradual Czechization of the local population in the early 20th century, particularly obvious in the changes of surnames, street names etc. The studied documents also reflect the nature of Terezín itself as a military, garrison – and last but not least – tourist town and a location of memory and memorialization, which highlights its potential as well as its limitations.

Jana Sumičová