In June 2022, eighty years elapsed since the so-called Case of Roudnice Students. During the several past decades a number of articles have been written about what had happened at the Roudnice secondary schools in June 1942, and the whole case is also featured in the Terezín Memorial´s project for youth called ”Being a Schoolchild in the Protectorate“.

The detention of more than 80 students of the Roudnice High School and Higher Industrial School turned out to be one of the the harshest Nazi crackdowns against Czech secondary schools in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The operation was part and parcel of the retaliatory measures taken against the Czech population following the assassination attack by Czechoslovak paratroopers on the acting Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich in May 1942.

What had really happened in Roudnice nad Labem a few weeks before the end of the school year 1941/1942, during the period of Nazi terror known as the “Heydrichiade”? According to the Nazi documents preserved on the case, a seventh-form student of a Roudnice school was allegedly suspected of masterminding murder or assassination of Alfréd Bauer, headmaster of a local German school. However, the true facts of the case indicate that the student had actually declared among his classmates that he would rather get rid of Bauer, but genuinely had no intention of performing the crime. Moreover, this student had always been perceived by other students as mentally unstable and his proclamations had not been taken seriously by his classmates. This particular character trait was also duly mentioned in the report sent by the Prague Gestapo to K. H. Frank. In fact, the report portrays the boy as something of a puppet in the hands of others. Furthermore, the report mentioned that he could have been instigated to carry out a similar criminal act by other students.

Students of the Higher Vocational School reportedly held debates hostile to the occupation forces and used the communist type of salutation – clenched fist – to greet one another.

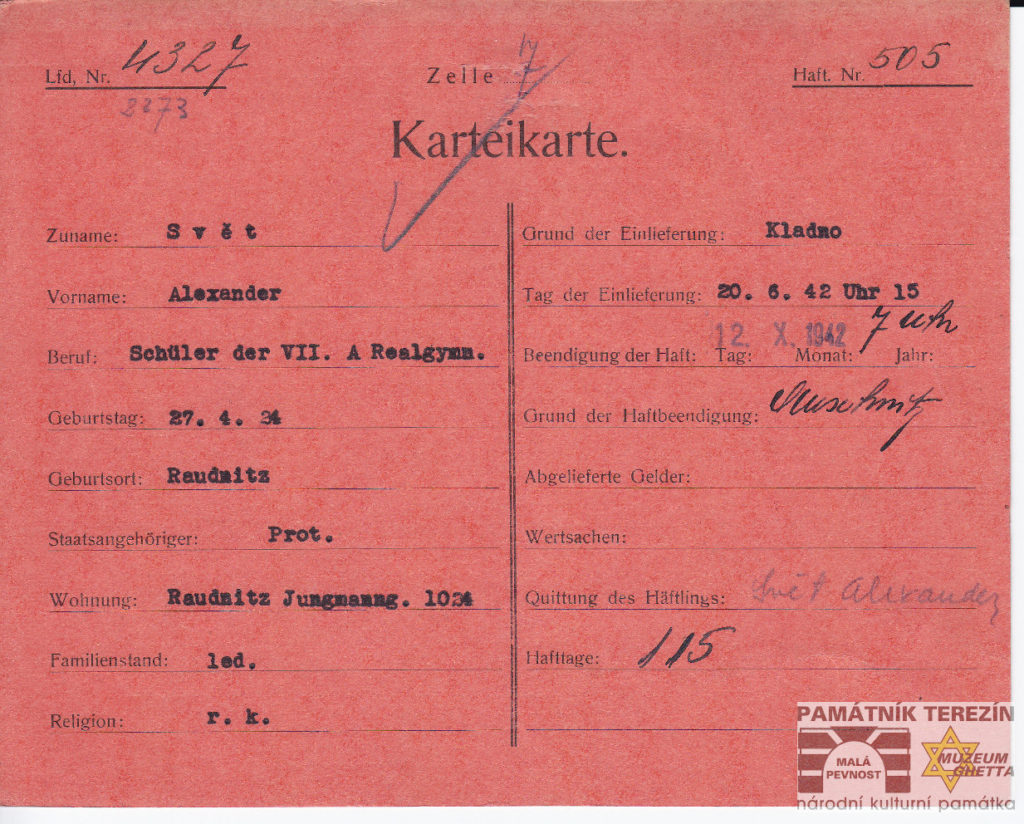

On the strength of the accusations charged against the students on the above grounds, 16 sixth-formers and almost all the students of the seventh-grade class A (boys and girls) of a Roudnice high school (30 students), were arrested during classes on June 20, 1942. Together with them 38 second-grade students of the Higher Industrial School were also detained.

They had all been taken to the Gestapo Police Prison in the Small Fortress in Terezín where they underwent interrogations, accompanied – especially in case of boys – by beatings. Then all the newcomers were issued basic necessities – blankets, bedsheets and mess bowls, and were put into their cells.

From the first day of their imprisonment boys had to work: initially being assigned to what were known as inner labor commandos – working only inside the Small Fortress. After several weeks they were also allocated to outer labor teams, working outside the Fortress. Inside the prison they would perform various jobs, e.g. as part of the building commando they built a swimming pool, made hay, with individual boys being sent to workshops to help the local craftsmen etc. During their work in outer labor commandos students would be assigned, for instance, to the Reichsbahn commando in Ústí nad Labem. That was a truly hard work, with inmates laying down rails and tamping sleepers. Other boys worked in the Glanzstof company in Lovosice, in the Elbe Chateau Brewery in Litoměřice or repaired a weir in the town of České Kopisty etc. Boys would also be sent in smaller groups and worked in other labor assignments. For instance, some students had fond memories of their work in the Litoměřice hospital where local nuns would take good care of them; the same was true of the ”Bast“ commando in Kopisty where they received very nourishing meals.

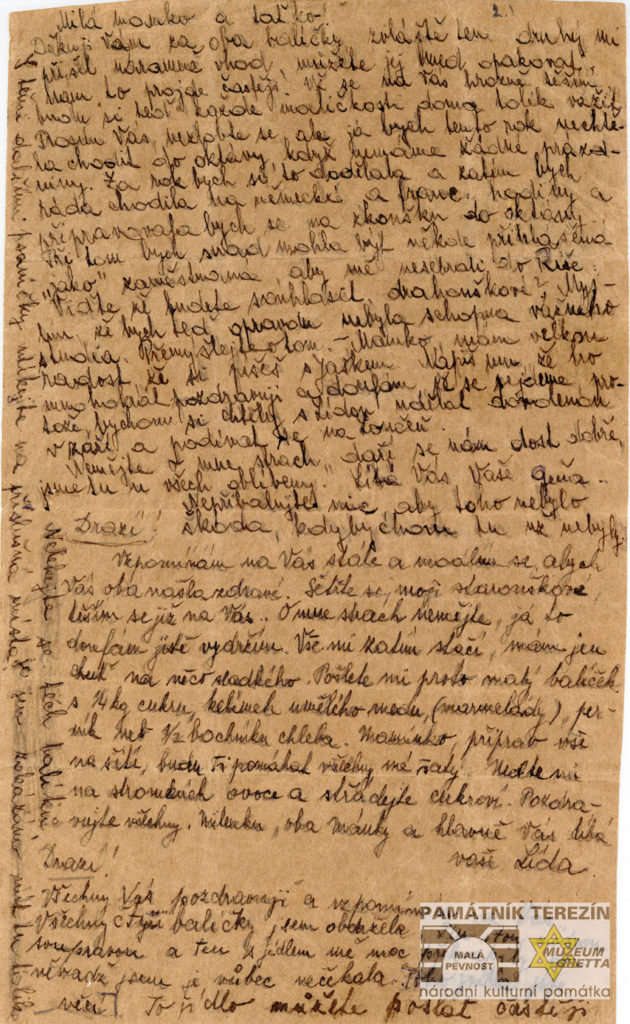

Girls enjoyed a slightly better status than boys. They were allowed to keep their civilian clothes and were not forced to do such hard work; initially only those girls who volunteered to work were assigned to different jobs. They helped in harvesting vegetables, grazed goats or cleaned offices etc. Girls, who also had more leisure time than boys, tried to make good use of their free time. They usually narrated to other girls the stories of the books they had read, recited poems, one of the girls, Ema Blažková, got hold of a pencil thanks to one of her former classmates in the Fortress and could paint. She captured several scenes from the cell and also the women´s courtyard, later on she would draw portraits of the female prison guards.

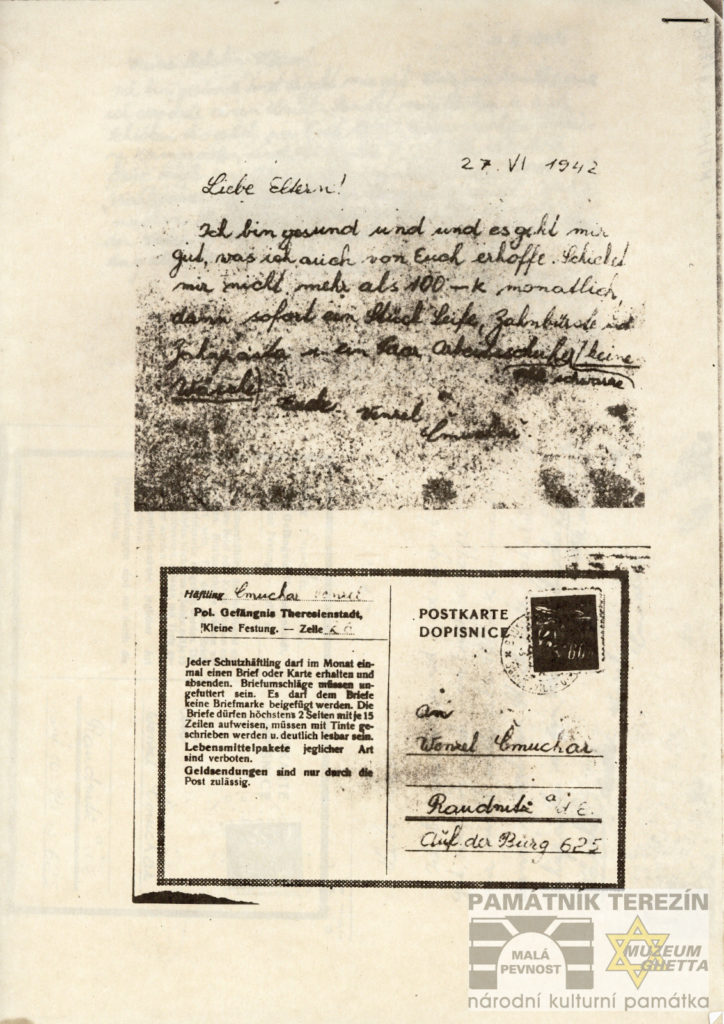

The students had restricted possibilities to exchange letters with their families. Officially, they were allowed, just like other inmates, once in a while to send from the Fortress so-called Postkarte in German with a specified number of words. However, thanks to civilian employees who got in touch with the students, for instance during labor assignments, they also had a chance to send home uncensored letters. Their families sought to meet their imprisoned children in person but that happened only very rarely and proved to be dangerous for all the parties involved. One of the students succeeded in meeting his mother during his work at the Litoměřice hospital. His mother sat down on a bench in the hospital park, while her son could talk to her for a few moments while watering the grass. Since the girls could not leave the Fortress as often as the boys, they preferred writing secret messages hidden in their dirty laundry sent home or handing them over to people who could smuggle the messages out of the Fortress.

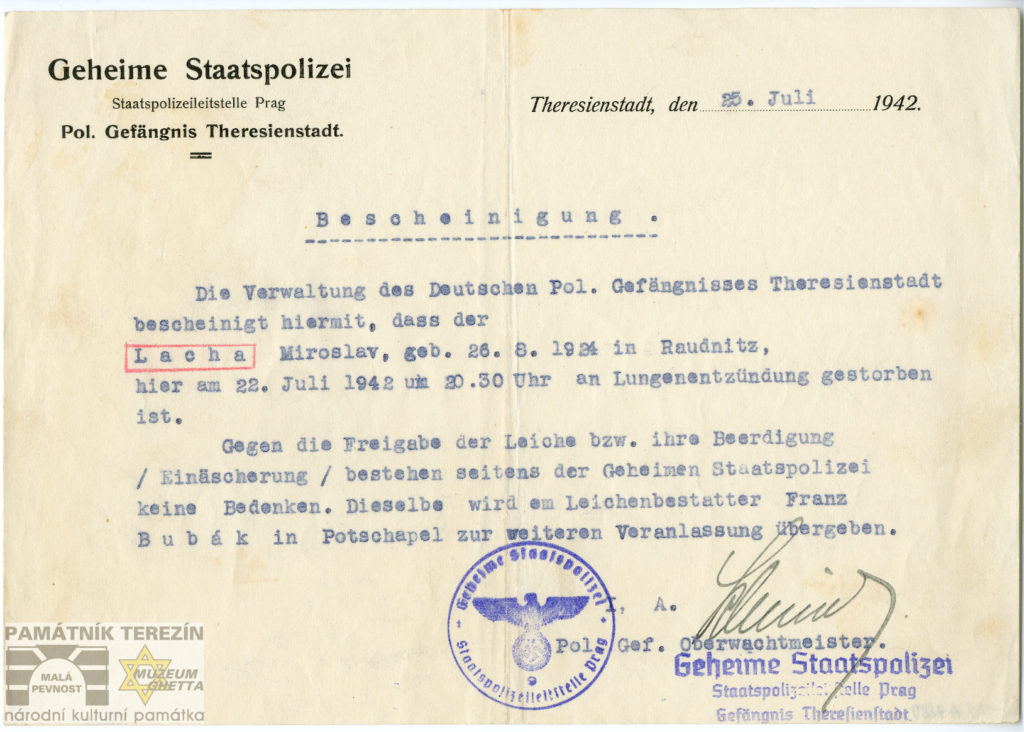

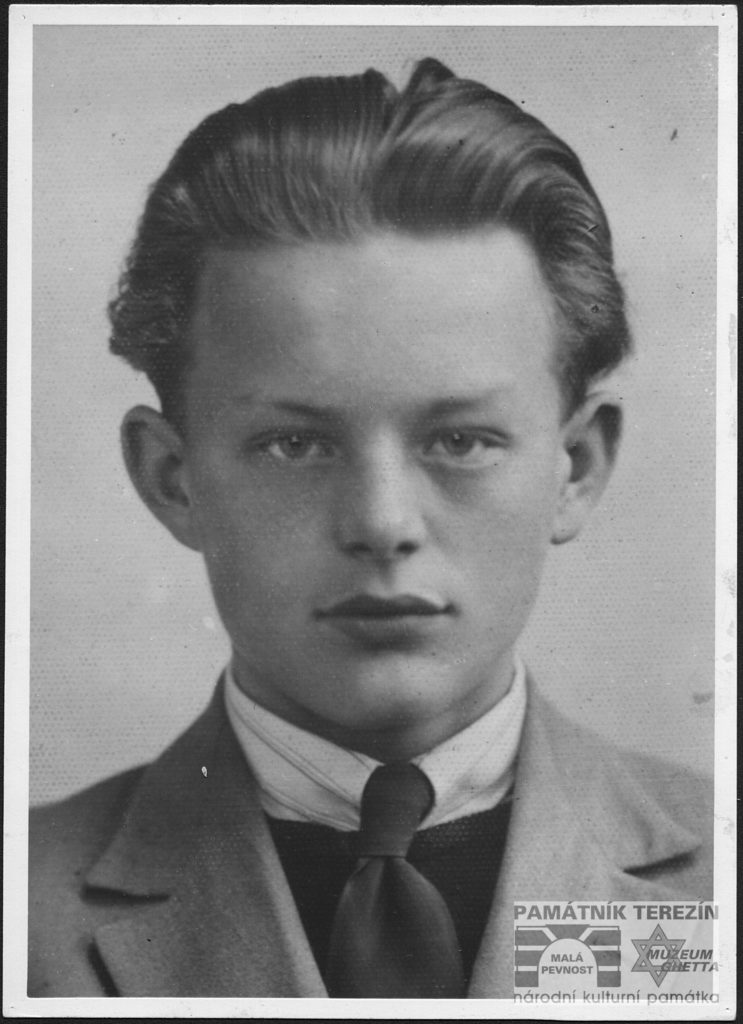

Soon afterwards, the impact of their internment, coupled with poor diet, the brutal treatment of the young inmates by the guards, and separation from their families showed itself in the aggravating health of the young inmates. Not only various diseases but also mental health problems gradually came to beset the young prisoners; such ailments worsened, especially in some cases, during the fall and winter of 1942 when students began to be released from the prison, while others had to remain. Two boys died already during the summer. First, in July 1942, high school student Miroslav Lácha died of pneumonia in the Small Fortress, and then Zdeněk Kubeš, a student of the Higher Industrial School in Roudnice, died in the Litoměřice hospital in August 1942.

As mentioned above, starting in the fall of 1942 students began to be gradually released from the prison. However, after their departure from the Small Fortress they were obliged to report to the Kladno Gestapo office where they were cautioned what to reveal about their incarceration. They were sent to the Labor Office to get their order to report for a specific job. Some of them worked in mines, others in the Roudnice-based MEWA company, a larger group was assigned to build petrol tanks at Hněvice. Girls would be frequently sent to the Křivoklát district to clear away brushwood, collect cones, beech nuts etc. Five Roudnice students were called up to do forced labor in Germany.

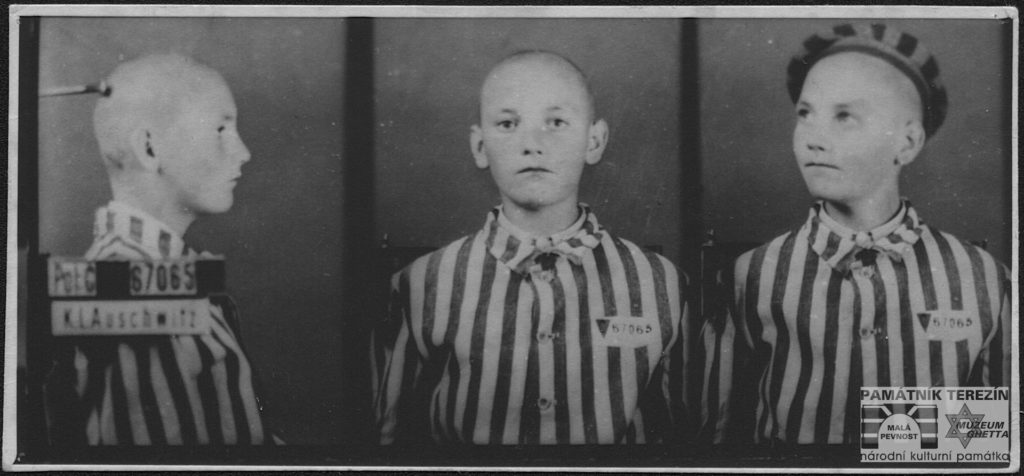

But not all the students had been lucky enough to be freed in the fall of 1942. The Gestapo report to K. H. Frank, compiled on the case, expressly mentioned the intention of deporting some of the students to other concentration camps. Individually or in groups, 19 boys were gradually transported to the Flossenbürg camp (2 boys), the Buchenwald concentration camp (6 persons) and the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp (11 students).

Also one girl, a student Sylva Rajtová, had been deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and perished there. The girl had been originally released together with other seventh-grade students in the fall of 1942 but was rearrested soon afterwards.

Soon after the arrival of the students, the horrible conditions in the camps, particularly in the Auschwitz concentration camp, began to exact their price in the lives of the young inmates. Nine students were murdered in the Auschwitz concentration camp. One student perished during his internment in the Buchenwald concentration camp, and another died one year after his release from the camp where he had suffered from a severe case of tuberculosis. And, as mentioned above, two students had died already in the summer of 1942. Overall, 13 students did not return home after the war.

On November 23, 1945, an Extraordinary People´s Court in Litoměřice sentenced Alfréd Bauer to death by hanging. He was found guilty in several articles – besides that he informed gestapo about student Dvořák for the reason mentioned above and he stated in his testimony at that time that German children in Roudnice are threatened by Czech youth – which all resulted in the arrest of the students and the subsequent deaths of 13 of them, Bauer informed also about some more citizens of Roudnice. He was found guilty also of fact that he was member of SD, SS and the National Socialist German Worker’s Party, he also propagated the Nazi movement and its regime. Alfred Bauer was executed in Roudnici n. L. later that day.

Naděžda Seifertová