The story of Dita Krausová.

Dita Krausová, originally named Edith Polachová, was born on July 12, 1929 into a Prague Jewish family. Her mother Elisabeth was a homemaker, father Hanuš was employed as a lawyer at the Social Security Institute, where he represented the interests of workers. Both parents enjoyed attending the opera, playing the piano, skiing, and mountain climbing. Additionally, her father had a strong passion for book reading and frequently recommended various titles to Dita for her reading list. Despite his serious demeanor and tendency to lecture, she and her father maintained a loving relationship.

Dita’s grandparents, grandmother Katy and grandfather Johann Polach, also lived in Prague. Her grandfather was a respected professor of Greek and Latin and later held the position of a Social Democratic senator of the National Assembly. Dita adored her frugal grandmother and she particularly liked to be affectionately called by her Edithlein.

The family was largely assimilated. Grandfather Johann left the Jewish community at a young age and his sons were non-religious. Dita first encountered the word Jew in 1938. She was in the third grade at the time, and one day a note appeared on her desk with the message “You are a Jew“. She took the note home and her parents tried to explain to her that the unfortunate events that were happening to Jews were occurring in Germany and not in their country. Shortly after that, Dita transferred to a Czech school.

Dita and her parents lived from 1932 in the Prague district of Holešovice in a rental apartment in the so-called “electric house”. It was a modern house for its time, but the Nazis forced them to leave it at the start of the war. They moved to an older apartment building in Smíchov, where the Polachs shared a four-room apartment with their grandparents. Later, after one year they were expelled from this flat and then they had to live in one room in the former Prague Jewish Quarter.

With the arrival of the Nazi occupiers, the family’s life radically changed. Dad was fired from his job. From September 1940, Jewish children were not allowed to attend Czech schools, and so Dita’s dream of entering grammar school after her fifth grade vanished. Her father, Uncle Ludvík (her father’s cousin), and his wife, Aunt Máňa, then taught her individual school subjects. Dita also attended private English and piano lessons and later went to educational clubs that met in the apartments of individual pupils.

In the meantime, Dita’s father found a new job in the office of the Jewish Community in Prague. At the Jewish community, Jews bought, among other things, yellow stars with the inscription Jude. Dita still remembers the day she was riding with her friend Raja Engländer on the back platform of the tram. Both girls were wearing the Star of David on their clothes for the first time, and they were concerned about the reaction of other people. However, while on the tram, a man exclaimed, “Look, two princesses with a golden star.” Dita and Raja smiled timidly, and so did the people around them. What a relief for the two girls!

With the start of transports to the Ghetto in Terezín, Dita’s study circle broke up, and for some time she helped a dentist´s assistant. In the spring of 1942, a vacancy opened up for her at the Prague Jewish school, where she made new friends, including Erik Polák and Zdeněk Ohrenstein. In addition, she also attended the Jewish Czech sport club Hagibor in Prague, where Jewish children could play, sing and go in for sports. Individual leaders talked to them about Zionism, life in Palestine, kibbutzim and settlements. Fredy Hirsch, the organizer and head of the youth program, proved to be a great idol for everyone there. Dita recalls the days spent on the playground as a happy and carefree period. But in this time the transports were already leaving and the groups were smaller and smaller. And also Grandma and Grandpa had been assigned to a transport to the Terezín Ghetto. Finally, in November 1942, Dita and her parents had to follow their grandparents.

Terezín

In Terezin, they were reunited with their grandmother and learned that their grandfather had died a few days before their arrival.

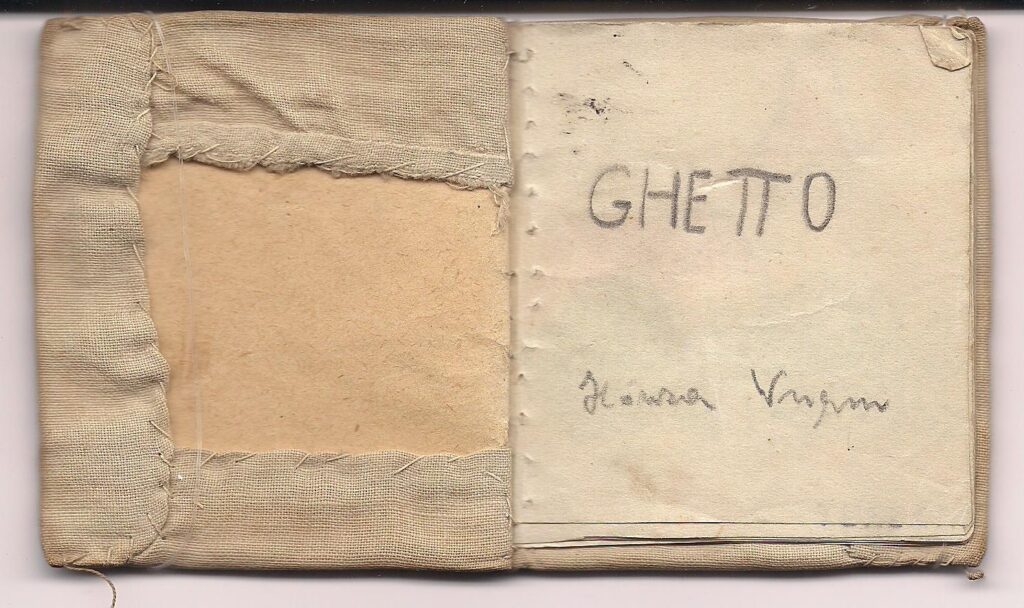

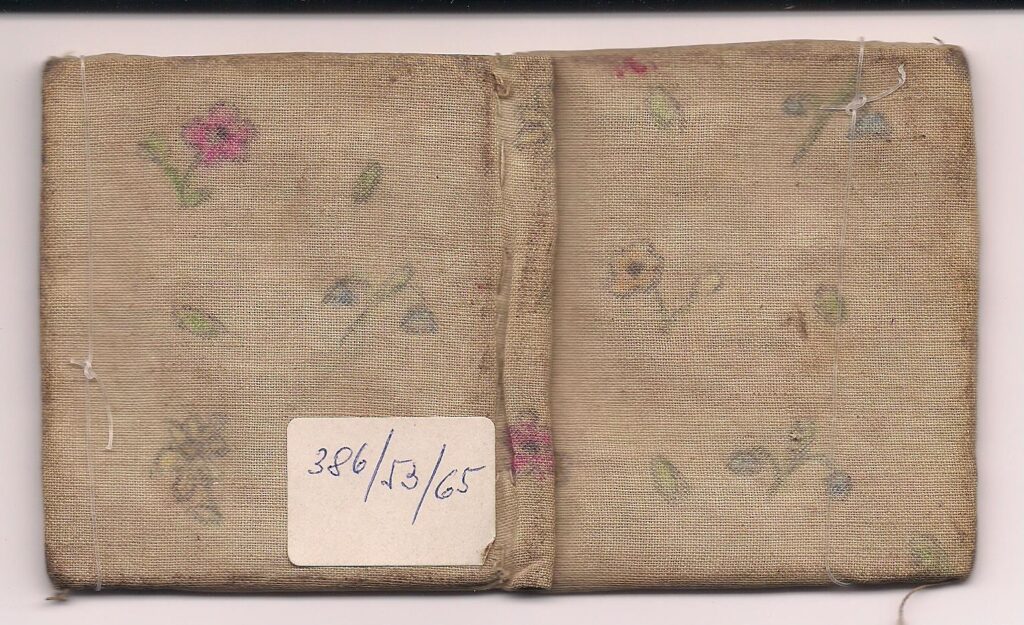

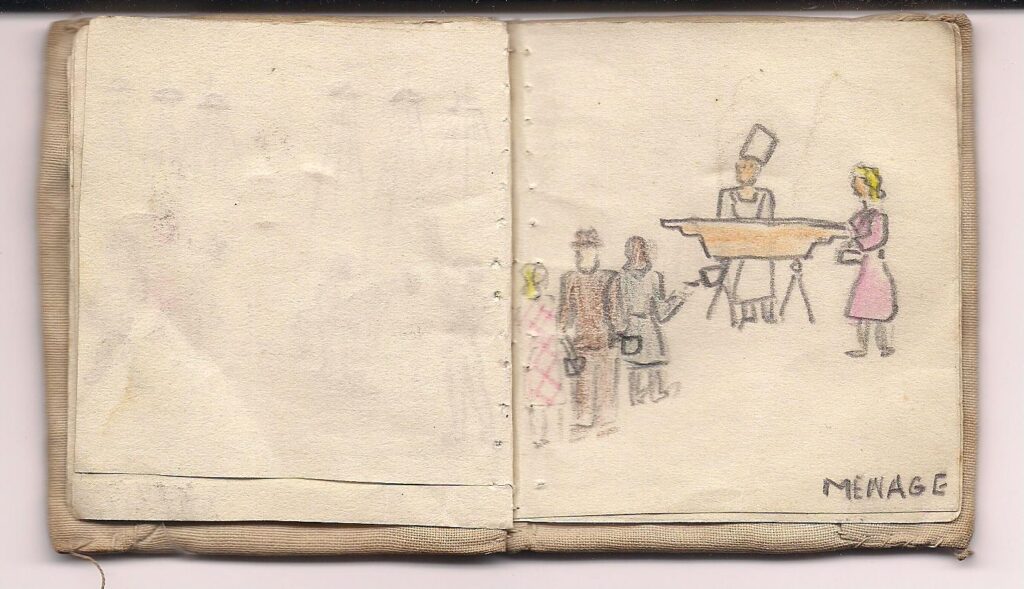

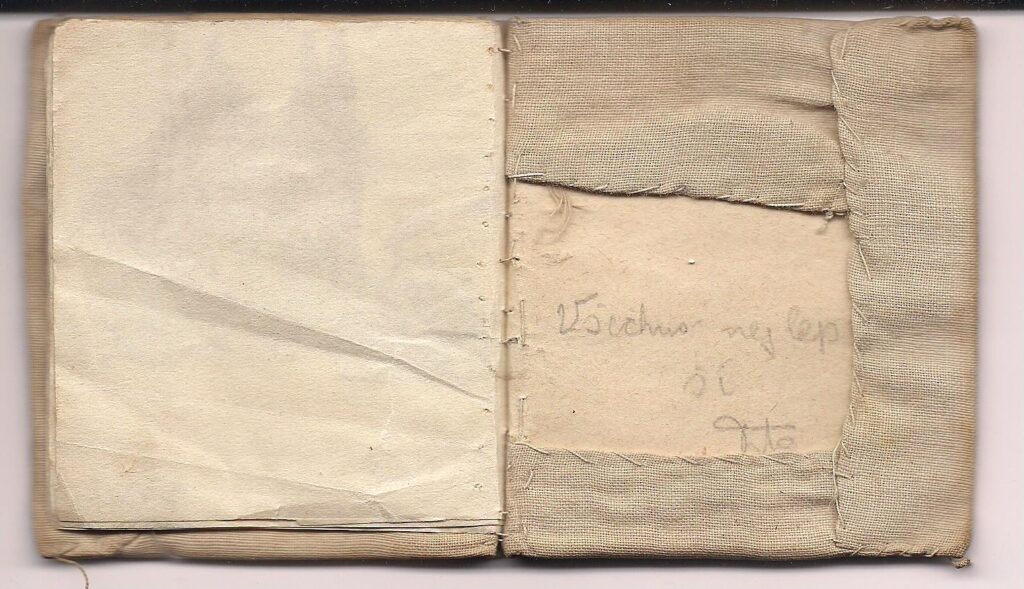

Initially, Dita lived in the Ghetto together with her mother. They share the room with other 20 women and slept on the floor. Dita longed very much for the possibility to be with the other girls in the girls’ home, designated L 410, where she had friends from Prague. And her wish finally came true. At first, she was placed in room No. 23, then in No. 25, where her friend Raja Engländer stayed. Despite of hunger and cramped conditions girls read a lot and recited from their favorite books they had brought to Terezín. Because of her age, Dita had to work. Originally, she was employed in vegetable gardens. Later, at her own request, she was reassigned to workshops, where imitation leather was made into wallets. She also used her skills to make birthday gifts for her friends. For example, she designed and made a small album for her friend Honza Wurm.

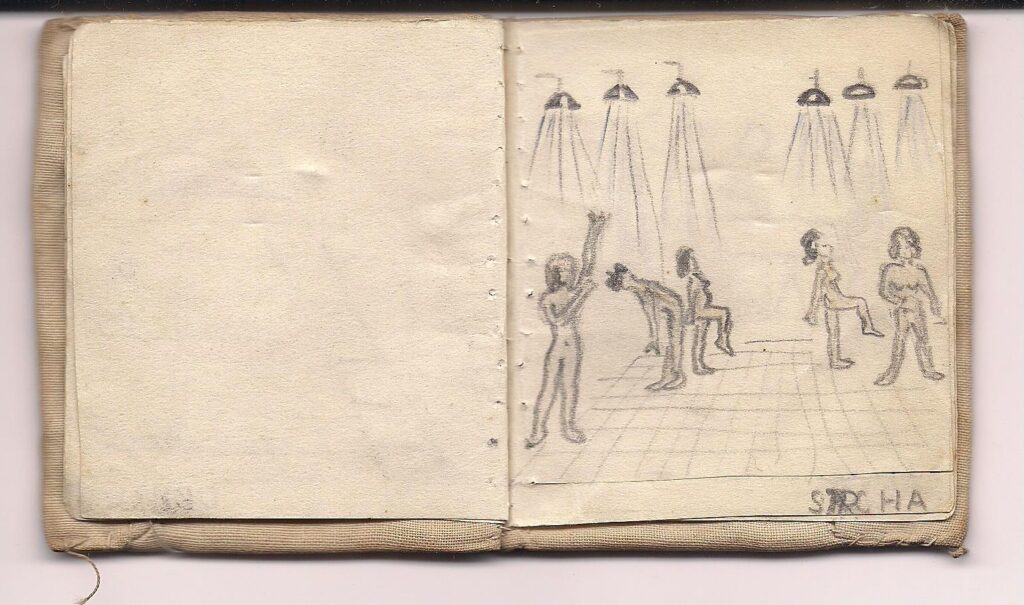

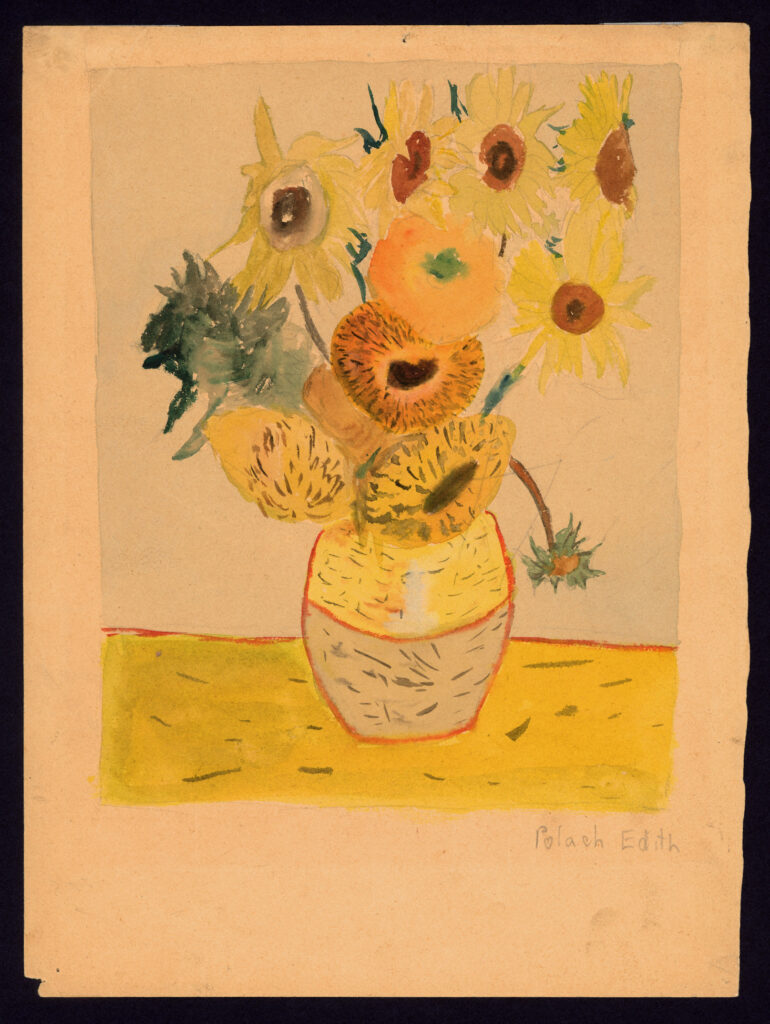

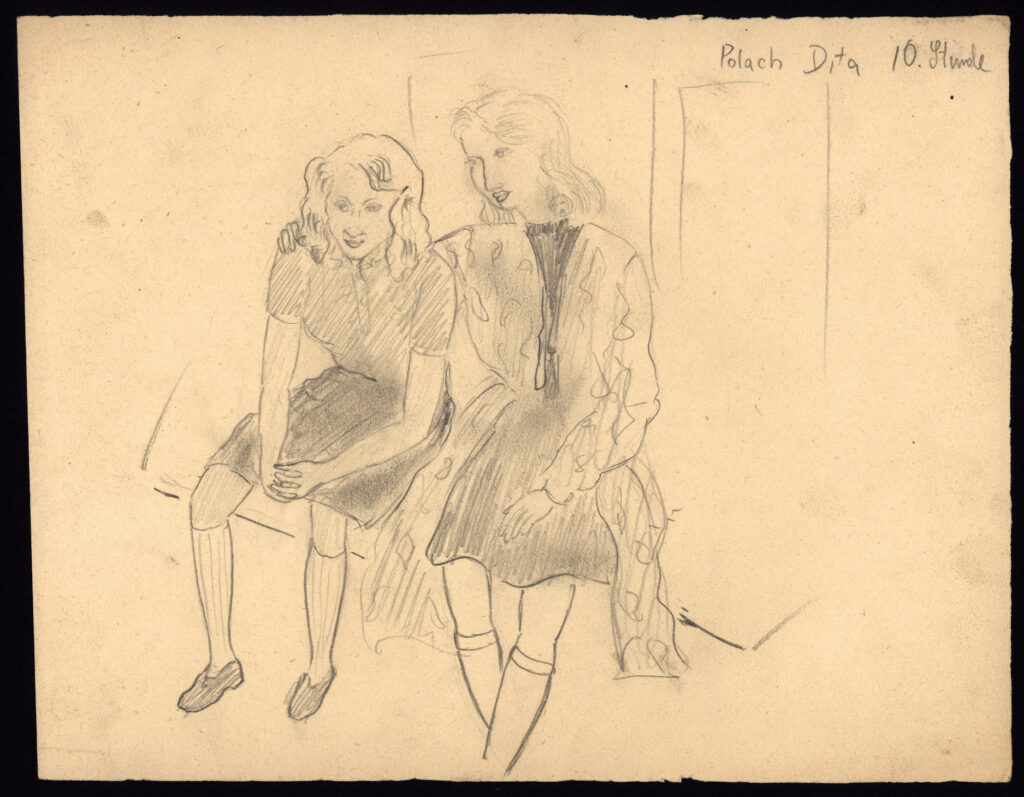

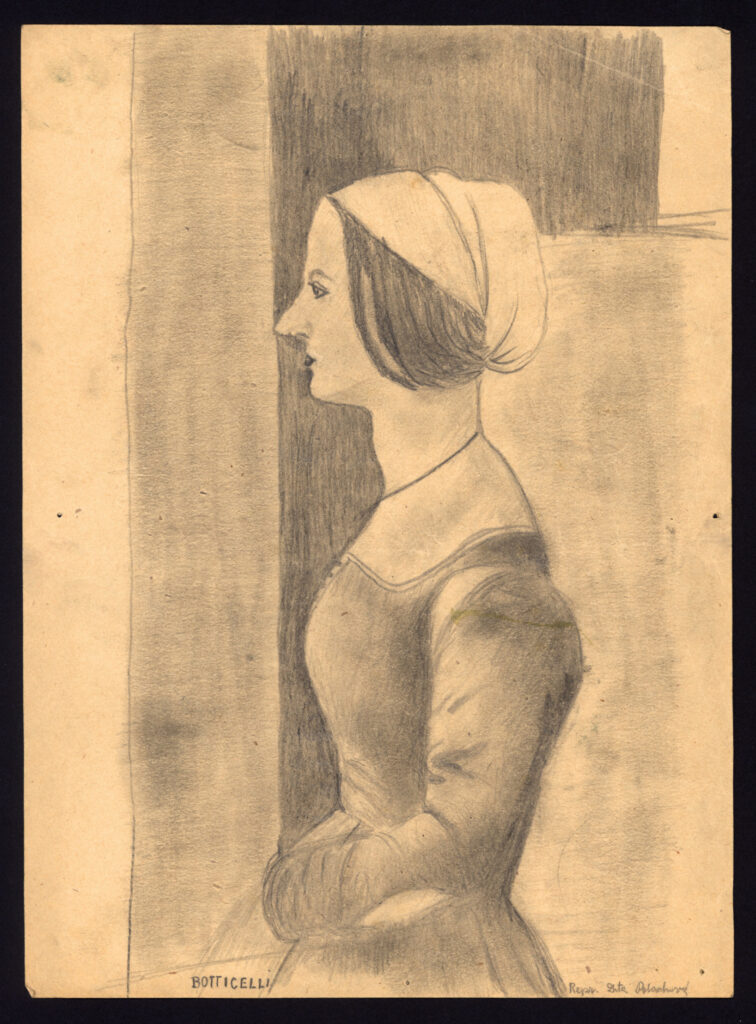

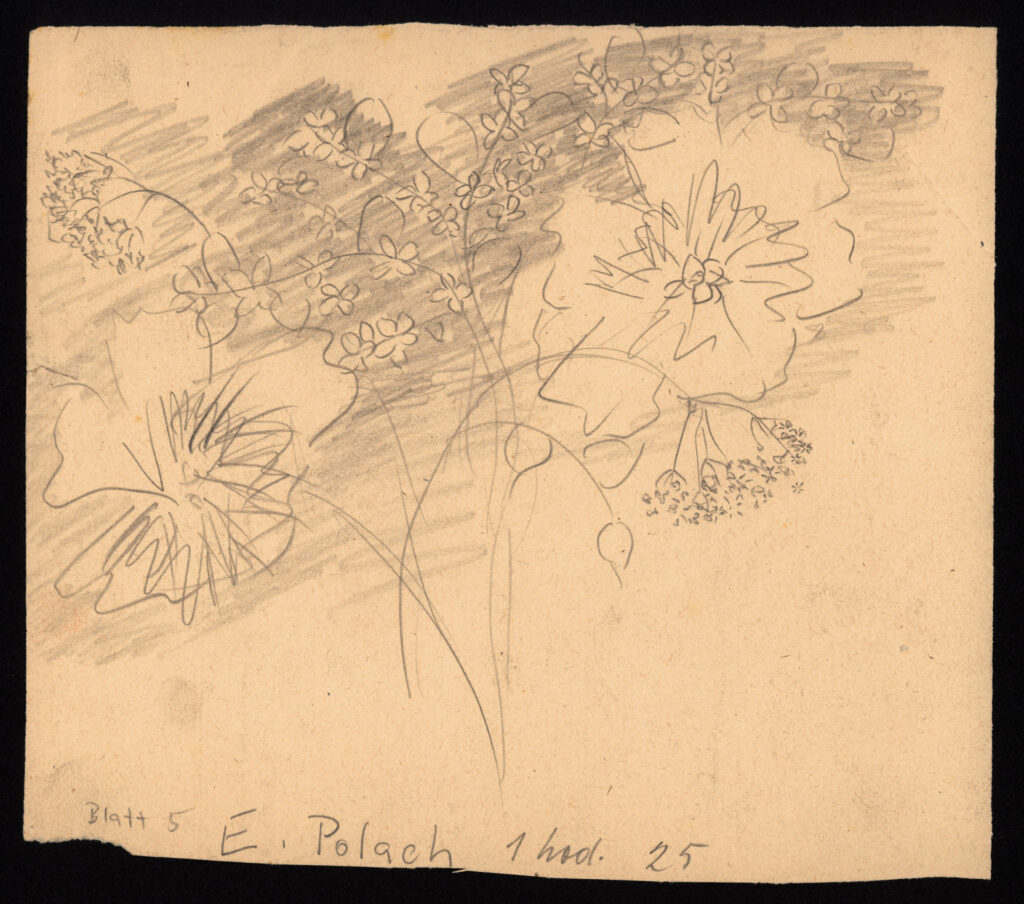

After work, the children attended secret lessons. They were taught by Friedl Dicker-Brandeis to paint and draw, but also to appreciate art. In the basement of the home, Dita attended rehearsals for the children’s opera Brundibár, conducted by Rudolf Freudenfeld. She sang in the choir. She even had the opportunity to play one of the leading characters ‒ Aninka. Unfortunately, Dita was too tall for the boy who played her partner Pepíček, so it was not possible to cast her in that role.

Aunt Máňa, the non-Jewish wife of the father’s cousin Ludvík, helped Dita and her parents even after the death of her own husband (who perished in the Łódź Ghetto) and sent them several food parcels to Terezin.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and the Terezín family camp

After more than a year in the Ghetto, Dita and her parents were summoned for transport to the East. They left Terezín under terrible conditions in the cattle wagons on December 18, 1943. Soon after arriving in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, they were all transported to the so-called Terezín family camp.

In this section of the camp, women and men, including children, lived together, but in separate barracks. Dita and her mother were placed in block No. 6. Their only possessions were a thin blanket, a spoon, a food bowl, and the clothes they were wearing.

During the day, the adults performed physically demanding work while the children spent time in children’s block No. 31. The older youth helped the educators. Fredy Hirsch, who played a crucial role in establishing this children’s block, appointed Dita as the “librarian of the smallest library in the world”. She was responsible for around 12 books that were borrowed from her by the leaders of children’s groups. Dita always had to remember well what she lent to whom because she had no pencil or paper. The classes that took place in the block were kept secret. Dita’s future husband, Ota Kraus, used to sit with his group of charges in the same corner of the block as Dita. In her memoirs, Dita wrote that she sometimes watched him, but never spoke to him there.

Several weeks after their arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau, the family experienced a devastating loss. Faced by the inhumane conditions of the camp, Dita’s father gradually lost the strength to fight for his life. He passed away on February 5, 1944. At that time, her mother was lying in isolation due to diphtheria and Dita had to inform her mother about her father’s passing through a crack between the boards.

After enduring a six-month forced stay in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, Dita and her mother were selected and left for Germany along with other female inmates assigned to perform forced labor. During the aforementioned selection, Dita used a “white” lie that probably helped her survive the selection. When asked about her profession, she told Dr. Mengele that she was a portrait painter, which may have aroused his interest. Dita and her mother then worked clearing the rubble in Hamburg and then went through the Neugraben and Tiefstack camps. The last place they reached at the end of the war was the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

The Bergen-Belsen concentration camp

Dita and her mother found themselves in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in early April 1945. The camp was in a state of collapse, with no food, the front approaching, and hundreds of people dying every day. One day, the guards left the camp. After their departure, the prisoners were left completely without food, without water, with dead bodies lying everywhere. Women around her were quickly turning into so-called Mussulmans, young and old. Dita knew of such cases from previous camps, but now it was more intense, and Dita subconsciously suspected that a similar fate probably awaited her. One was exhausted to the point of fatalism, feeling nothing. Dita’s emotions were suppressed ‒ except for her friendship with Margita (Barnai), whom she had befriended in the Neugraben concentration camp, and except for her concern for her mother. At the end of April, finally the expected liberation came and with it great relief. Thanks to her command of English, Dita began working as an interpreter for the British Army. She later fell ill with typhus, which she eventually overcame.

Dita and her mother wanted to apply for a convalescent stay in Sweden. But a confirmation from the hospital of discharge from quarantine was needed. They came up with the idea that her mother would go to the hospital for a few days with a pretended illness and then let herself be released. However, her mother suffered a sudden abdominal attack in the hospital and after a short hospitalization she died unexpectedly on June 29, 1945. The young girl was wondering what would happen to her now. She was less than 16 years old and lost both her parents. She came back to Prague alone.

Prague

Dita arrived in Prague on July 1, 1945. Her first steps led to her Aunt Máňa, who welcomed her and let her live with her. Dita then learned that her beloved grandmother had managed to survive in Terezín until the end of the war.

After the war, it was essential to take care of many things, including getting new documents. And so it happened that one day Ota Kraus was standing in front of Dita in one of the queues to obtain one of those documents. She knew him from the time of their imprisonment in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. They began to meet and fell in love. Dita returned to school, studying first at a grammar school, then at a school of decorative arts. Ota enrolled in college to study comparative literature, English and Spanish. He also applied for the return of the factory manufacturing women’s underwear, which had been built by his father. Dita and Ota got married on May 21, 1947 after completing the necessary formalities. At that time, in the summer of 1947, Ota was named proprietor of his parents´factory, however not its owner. This allowed the couple to move into the villa. The villa was used as offices. And Dita and Oto turned two of the rooms int their new home. Their son Petr was born in December 1947.

Shortly after the communist coup in February 1948, the factory was nationalized and its old-new manager eventually managed to have the family chased out of their villa. They decided to leave Czechoslovakia and go to the newly established State of Israel. Otto was an enthusiastic Zionist since his youth; he liked the fields and dreamed of a kibbutz, so the decision was obvious. However, leaving the country proved to be problematic and bureaucratically demanding, and they were not able to leave until more than a year later, in the spring of 1949.

Israel

When they first got to Israel, they lived in tents in reception camps. They started out in Sha’ar Aliyah and then moved to Pardesiya. The hygiene standards in the camps were inadequate and little Petr fell ill as a result. Dita was then helped by relatives in Jaffa, moving into their tiny apartment with her son. Her aunt then found a doctor for Petr and went with them to the outpatient clinic for check-ups because Dita didn’t speak any Hebrew, which was necessary. Ota used to visit them on weekends, working hard in agriculture during the week. After a few weeks, Petr was back to full health. In mid-July 1949, Ota managed to find accommodation in the village of Sha’ar Chefer, where they lived for several months. After about a year of living in Israel, they finally let themselves be persuaded to move to the kibbutz Giv’at Hayim.

It was not easy for them to get used to the new way of life, which was to some extent organized by the community and based on the equality of all its members. It was especially difficult for Dita to put little Petr in a children’s home, where he lived together with other kibbutz children and could only see his parents in the afternoon. Dita and Ota did not realize at all how traumatic it must have been for the boy himself. In addition, Petr had to be given a new name to make it easier for children to pronounce. And so his first name was changed to Simon.

In the kibbutz, Dita first worked in its dining room, then in the tailor’s workshop and finally in the shoemaker’s shop. Her husband Ota had several auxiliary jobs before becoming an English teacher. Their daughter Michaela was born in 1951.

Dita and Ota were unhappy with their lives in the kibbutz, especially Dita who never felt at home there, who felt like she never truly settled in. For his part, Ota held a different view on the issue of his literary work than the kibbutz movement, and after seven years, the family decided to leave the kibbutz. They moved to Hadassim, where the children finally lived with their parents together. Ota worked at the local boarding school as an English teacher and devoted himself to writing novels and books of short stories. Later, he became interested in graphology. He enrolled in Tel Aviv University and became a recognized expert in the field of graphology. Dita decided to study at the Faculty of Education. After successfully passing the exams, she began teaching English and worked as a teacher for the next 28 years.

In the late 1950s, the family’s life was turned upside down when they discovered that their daughter Michaela was suffering from an incurable disease. This happened shortly after they moved to Hadassim. Michaela began to experience health problems, particularly severe fatigue. Concerned, her parents took her to see a doctor, who observed a very low sedimentation rate in her blood sample and initiated a series of tests. Ultimately, she was diagnosed with juvenile cirrhosis, which was devastating news for the family.

The disease was somewhat stabilized for several years with the help of medication, but it was only a temporary relief. Dita and Ota sought better treatment, consulted various specialists, and contacted hospitals in the USA and Switzerland. However, nothing proved effective. A great source of comfort for the parents during this challenging time was their youngest son, Ronny, born in 1961. When Michaela was sixteen, her condition began to deteriorate again, and four years later, she passed away.

The enormous mental strain in the family took its toll; Ota suffered a heart attack in the autumn of 1970.

The parents faced another challenge in life when they discovered that their oldest child, Petr-Simon, was also suffering from poor health. During his military service, he began showing signs of mental illness. Despite marrying and having two sons with his wife, Miriam, Simon’s worsening illness led to significant communication problems, resulting in frequent job changes and ultimately the breakdown of his marriage. Simon received treatment and was under the care of psychiatrists, often requiring hospitalization. Eventually, he settled in Netanya, where Dita and her husband, when they retired, supported him. Simon worked as a nurse until he quit around the age of sixty and lived on a small disability benefit while taking numerous medications. Until his passing in 2016, his mother Dita remained a great source of support for him.

Ronny, the younger son, has been a joy to his parents since he was a child. From an early age, he wrote articles to a school newspaper and also swam, even competitively. He also played the trumpet and was admitted to the prestigious youth orchestra in Tel Aviv. He studied social care at Tel Aviv University. During his military service, he met Orna, a girl from a kibbutz near Nazareth. His father Ota didn’t like the girl very much and claimed that she wasn’t suitable for his son. Ronny was later sent by Ota to study in the USA. When Ronny came on vacation a year later, he met Orna and decided to marry her. They went to the United States, studied there and waited for Ronny′s father to come to terms with their relationship. Orna, who originally danced in Israel, also studied there and became a physiotherapist. Ota finally gave his consent and the wedding took place in 1991. Later, Ronny and Orna had a son and a daughter.

After 1989

After 1989, the Krauses began visiting Czechoslovakia regularly and reestablished contact with their old friends. In addition, Dita also sought out girls from Terezín and Auschwitz, with whom she would then meet every year in the Giant Mountains. Her husband Ota passed away in 2000 after a long illness.

Dita currently lives in Israel but often visits the Czech Republic. She has devoted part of her life to holding debates about the Holocaust with students in Israel, the Czech Republic, and other countries. Earlier this year, she gave the keynote speech during the Terezín Commemoration. With her distinctive demeanor and sincere messages, she always touches the heart and soul of many listeners.

Her work in the children’s block at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp inspired the Spanish writer Antonio Iturbe to write the novel “The Auschwitz Librarian“. Dita Krausová wrote her own autobiography “A Deferred Life”, the true story of an Auschwitz librarian. She is also the author of the book “Life with Ota“, in which she chronicled the life story of her husband.

Jana Švarcová, Naďa Seifertová

Source:

Dita KRAUSOVÁ, A Delayed Life, London 2020.

Dita KRAUSOVÁ, Život s Otou (Life with Ota), Prague 2022 (in Czech).