Events That Shook the Ghetto

During the three and a half years of its existence (from November 24, 1941 until May 1945) the Terezín Ghetto passed through specific developments and changes. The following article is aimed at tracing its very beginnings.

From the first days it was the Nazi Command that wielded ultimate power and held the key position in the Ghetto. It also issued all the instructions and especially numerous bans. On December 6 the SS Commander Seidl issued an order for the separation of male and female inmates. Women with children under 12 years of age were transferred from their original site in the Sudeten Barracks to the Dresden Barracks; the Magdeburg Barracks was reserved for the Jewish Self-administration. From then on, any contacts between men and women were prohibited, while children and adolescents were allowed to visit their parents only once a week.

Other bans resulted from the fact that until the middle of 1942 Terezín´s original civilian population also lived in the town. They were forbidden by the Command to speak with the Jews, help them or come into any contact with them. But soon enough cases of violation of such orders were discovered – some local citizens were found to have helped the inmates by sending out their letters and arranging meetings with prisoners´ family members. As early as on December 2, 1941, inmates´ postal contact with the outside world was prohibited under the threat of death penalty. However, on December 7 the Ghetto Commander received specific information on the smuggling of correspondence, complete with the names of the persons involved. That was why many inmates were locked up in the Command cellars, the so-called bunkers; this was followed by investigations and negotiations with the Terezín Command’s superiors in Prague on the mode of punishment.

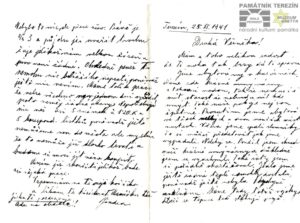

A copy of the first letter of Jindřich Jetel to his wife that was sent from Terezín, part 1. Private archive of Ludmila Chládková.

The thousands of prisoners received information on everything that was going on in the Ghetto, and primarily on what was prohibited, in the shape of printed orders of the day (Tagesbefehl = TB). The Jewish Self-administration began issuing them on December 15, 1941, while addressing the problem of illegal mail relatively very often: TB No. 8 and 9 from December 23 and 24, 1941 respectively briefed the Ghetto inmates on the new arrests due to the smuggling of letters, while the official quarters warned that all mail would be stopped. Soon afterwards, TB No. 12 reported on the ban of mail ordered by the Commander. For its part, TB No. 23 from January 10, 1942 announced: As ordered by the Security Service Commander, nine inhabitants of the Jewish Ghetto had been sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence has been carried out today…

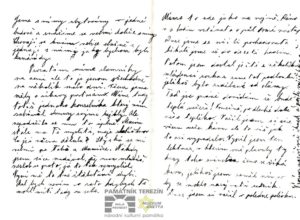

A copy of the first letter of Jindřich Jetel to his wife that was sent from Terezín, part 1. Private archive of Ludmila Chládková.

This cruel statement was preceded by days and sleepless nights when the Jewish Self-administration had to arrange the construction of gallows behind the Aussig Barracks, find a hangman and have a mass grave dug out before the execution. In addition to the victims themselves, the Jewish Council of Elders, gendarmes as well as SS-men, including the Camp Command, were present at the execution. The convicts received the sentence “for the defamation of Germany“ bravely, some of them shouting “this won’t win you the war“. Kaddish, a prayer for the dead, was secretly officiated in the flat of a Jewish Elder after the execution.

Another seven men were executed for the same reason and in the same manner on February 26, 1942. In the following years there were no other executions in the Ghetto, while violations and trespassings against the prison rules were punished in less drastic ways.

Fate of Jindřich Jetel

One of the nine men executed in the Ghetto on January 10, 1942 was Jindřich Jetel. Between 1992 and 1994 his wife Věra gave us several written documents on the whole case. In them she aptly described their marriage “as a wee bit of happiness and so much tragedy“.

Jindřich, born in Prague in 1920, was a Jewish half-breed, registered with the Jewish Religious Community. Coming from a clerical worker family, he was an electrical engineer by profession. Věra Kurzová, born in Vršovice in 1916, who was of Aryan descent, also joined the Jewish Religious Community before the war. She worked as a private clerk. Both knew each other since their studies and despite opposition of their families they eventually married in Prague on June 5, 1941.

Commenting on the events in Terezín, Věra Jetelová said that after Jindřich´s departure in transport Ak I on November 24, 1941 she received from him several letter assuring her that everything would be all right. In a letter from November 25 he described accommodation in Terezín, work in stuffing mattresses with straw as well as his satisfaction with having a washroom with running water. But he also wrote he had missed his wife and her constant chattering. On November 27 Jindřich wrote to ask for a larger soup dish. Just as other women Věra Jetelová set out to Terezín in December. She came there together with Mrs. Stránská (her husband was also later executed). They saw their husbands, gave them parcels and talked to them across the fence at the barracks. They could not know they were being watched and would be detained. Two gendarmes took them to a guardroom at the Sudeten Barracks. When ordered to hand over clandestine letters from several other inmates from the Ghetto the two women were asked to deliver to their families in Prague, the gendarme began throwing the letters into a large stove. All the signs were that the incident with the letters would not be officially resolved. Then the gendarme, by that time in the presence of a German soldier, wrote a protocol. The women were released and cautioned never to try to visit Terezín again. Before their departure they caught sight of a group of detained men, including their husbands. Then Věra experienced many days filled with apprehensions about the fate of the men in Terezín. All the contacts ceased, a food parcel sent to Jindřich before Christmas was returned to her completely mouldy. Her Prague acquaintances, women whose husbands were also imprisoned in the Ghetto and who had learnt about the execution of the nine selected inmates on January 10, 1942, tried to keep Věra in the dark about this. She learnt the cruel truth much later. She received an official confirmation of the execution of her husband from the Jewish Religious Community in Prague only one and a half year later.

A current location of the memorial with the names of the executed men in the Ghetto Terezín – the Jewish cemetery in Terezín, 2012, photo: Radim Nytl, Památník Terezín.

At the end, Věra Jetelová wrote: When I met Jindřich, we had no idea what a threat was hanging over us and the whole world. For her, Terezín then turned out to be forever a place of the worst injustice that could not be forgotten.

Chl