Hana Hnátová, née Lustigová, was born in Prague on June 20, 1924 into a Czech-speaking family of a trained sales clerk and a seamstress, née Löwyová. The Lustig family lived in Prague´s Libeň quarter. The economic crisis in the 1930s dramatically affected her father´s business who earned his living as a retailer in textile goods.

In terms of its spirituality, the family oscillated between atheism and religious faith, as corroborated by Hana´s recollections of their Sabbaths when mother Terezie and daughter prayed, while father Emil and son Arnošt, later a distinguished Czech writers and journalist, were playing cards. Hana explained her mother´s religiousness by her roots in Moravia, a region which, in Hana´s opinion, has remained more religious than Bohemia to this day. Unlike her daughter and son, mother still refrained from eating pork. Not even the war events had managed to shake her mother´s faith in God to whom she also attributed her survival of Auschwitz. On the other hand, Hana explained her father´s atheism by his origin in Bohemia and also by his harrowing experience of a soldier fighting on the Italian front in World War I and in the postwar military clashes between Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

Since 1938, a small cousin named Věrka lived in the family; her parents (her father was brother of Hana´s mother) had sent her to Prague from Moravská Třebová because of the constantly rising aggressiveness of both Heinlein supporters and ordinary inhabitants and the Munich agreement. Unfortunately, Věrka was never reunited with her parents.

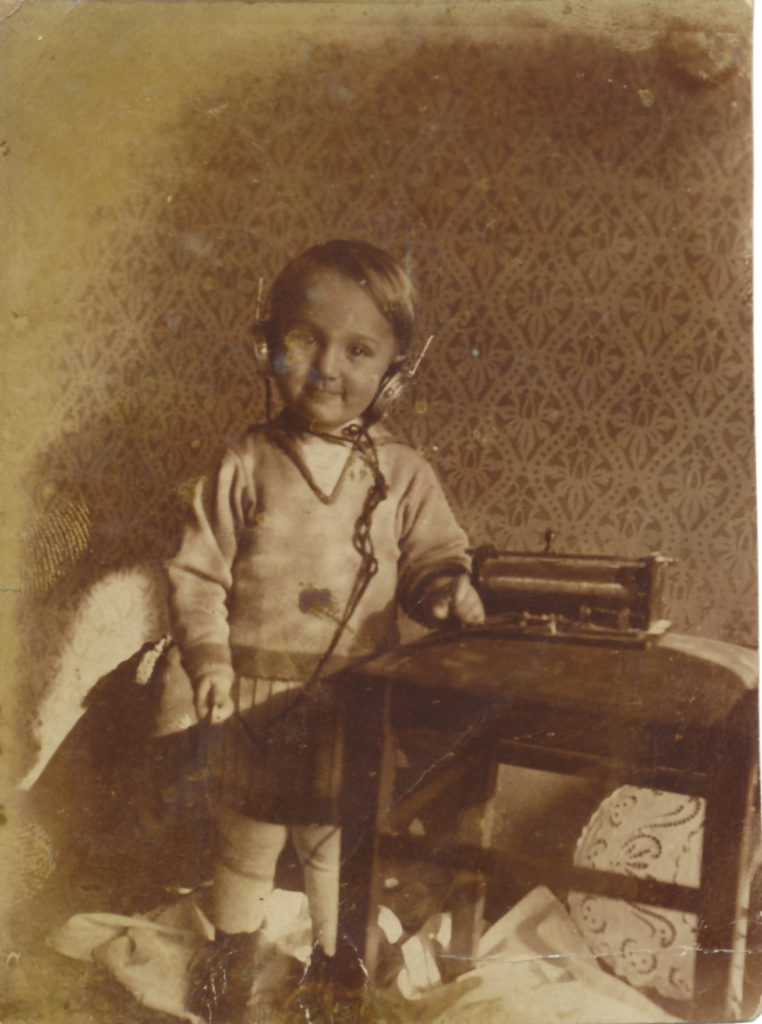

The Lustigs family at the ZOO, private archive of Hana Hnátová.

The Lustigs Family, from the left: Hana, her mum Terezie Lustigová, her brother Arnošt, cousin Věra and father Emil Lustig, private archive of Hana Hnátová.

Hana, who attended a high school in Libeň, was expelled in her fifth grade as a result of the newly applied anti-Jewish measures. In addition to many other bans, the family was not allowed to own a radio set; that was why her father used to go to a neighbor to listen to the news, and back at home he would report on Hitler´s speeches with disparaging comments.

Hana Hnátová left for the Terezín Ghetto by transport Cc on November 20, 1942 together with her mother, brother and cousin. For the time being, their father stayed in Prague, being employed as a building worker on the construction of a playground in the Smíchov district; therefore, he was in a position to help his family by sending food parcels containing soup stock cubes, margarine and gingerbread.

Hana still retains a treasured memory of her stay in Terezín from the summer of 1943, when her brother Arnošt, owing to his inadequate German, managed to get her and himself out of a transport to the East. As a reason for reclaiming them from the upcoming transport he wanted to say in German that their father had suffered war injuries during World War I (kriegsbeschädigt), and mistakenly said that their father was involved in the war industry (kriegsbeschäftigt, according to the note by Mrs. Hnátová). On this occasion, both were taken out of the transport list.

In the fall of 1944, during a wave of liquidation transports from Terezín to the East, 20-year-old Hana was saved from being put on a transport list thanks to her labor deployment. First, her father and then Arnošt were deported from the Ghetto. This was followed by a summons to report for a transport delivered to her mother and her cousin Věrka. At that time, Hana volunteered to be deported with them. Her application was granted and the three of them left for the East (the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp) by transport En on October 4, 1944. Upon their arrival to the camp they all succeeded in passing the selection together and, after less than three weeks, departed with a group of other female inmates to Freiberg in Saxony to work in the military aviation industry. Hana handled a drilling machine and riveted nuts. The three women stayed in that camp until the spring of 1945. Freiberg fell under the administration of the Flossenbürg concentration camp, and the women prisoners were sent to Flossenbürg. However, due to allied air-raids and advancing troops their train had to go south. On their way the inmates could watch the aftermath of the air-raids on Pilsen; during a stop at Horní Bříza they experienced a great show of solidarity when the local inhabitants had been allowed by the Nazis to bring some food to the prisoners in the train. To this day, Hana remembers that cup of coffee and a piece of bread she was given by the locals. Eventually, her final station was the Mauthausen concentration camp where they were liberated by the US Army.

After the war Hana passed her school-leaving examination as well as additional studies needed to qualify as a clerk-correspondent: her mother after recovery got back to her profession of a dressmaker; both ladies had to work to help Arnost and cousin Verka who decided to continue their education. She then got married and now has her two grown-up offspring who have already founded their own families. Initially, Hana tried to forget all her Holocaust memories as soon as possible, and for a long time she refused to share them with her children or her colleagues at work. But today she feels the responsibility to recall the horrors of the war so that other people would never forget them.

St