Ilse Weber´s correspondence, written during the 1930s and 40s, was published as a book in 2012. These are primarily letters sent by Ilse to Britain, to her best friend Lilian von Löwenadler, daughter of a Swedish diplomat, and later also to her son Hanuš. The letters are very open and sincere: readers will learn many details concerning the everyday life of the family, her recollections, opinions of politics and literature, insights on the life in the border region, and many other aspects.

The Weber family lived in Vítkovice near Ostrava. At home they spoke German but their sons Hanuš and Tomík attended Czech schools and both spoke fluent Czech… As for Ilse, she undoubtedly felt her kinship with both the German culture (she was fond of wearing the dirndl, for instance) and the Czech one (she admired Masaryk, loved Karel Čapek and exchanged letters with him). In her letters Ilse mentioned that as a practicing Jewish family they celebrated Chanukah, Pesach, and Prophet Elijah visited the family (instead of St. Nicholas) etc.

Commemorative flyer – Simchath Thora, October 1943; Terezin Memorial, so called Heřman collection, PT 3912, © Zuzana Dvořáková.

During the 1930s, Ilse quite definitely began to espouse the views of Czechoslovakism. She clearly saw the dangers coming from Germany through the Heinlein Party – she wrote on March 28, 1938: Lilian, you should not forget that there are Germans in this country, Germans with whom we have lived in peace and friendship but since the early days of the Henlein movement all of them are Hitler´s supporters. I know none of the Germans who were my friends until recently who would not be lovingly looking up to Germany… Soon afterwards – probably sometimes in early June 1938 – she experienced a dose of Czechoslovak anti-Semitism and wrote: Our children are, of course, Czech but we, adults, spoke German together, after all, it is our mother tongue. And the Czechs are now saying: “How can you speak that language when the Germans harmed you so much?” On the other hand, they ridicule our attempts at speaking Czech: “Look at those Jews! They know how to adapt themselves!” And the street demonstrators recently did not shout only “Germans out!” They did not forget us either…

The situation was still worse after “Munich” (signing of the Munich Agreement in September 1938 – editor´s note) – her letter from October 10, 1938 reads: Anti-Semitism has been spreading alarmingly here. People are shouting at us: “The Jews are to blame for everything! The Jews have sold us out!” Where is the logic of this? But hatred needs no logic…

From her early years, Ilse showed three different penchants: to children, literature and music. Thanks to her hard-working nature she managed to combine all three preferences, and the results came in several successful books of fairy tales and radio programs for children. The birth of her sons in 1931 (Hanuš) and 1934 (Tomík) affected her professional career but did not put a premature end to it. Her letters show that in spite of her concern for the family Ilse maintained her contact with the Czechoslovak Radio. Nonetheless, the turbulent era gradually put paid to those activities as well, for instance on February 13, 1938 Ilse wrote: …For next month I was promised by Ostrava Radio station a program of reading from my “own works” and I am also expected to prepare a program for children on Mother s Day (in May). So far I haven´t got any children to work with, that amiable teacher I have been working so well for years seems to have recently caught the germ of anti-Semitism and has been prevaricating. What a pity!…

During the late 1930s the overall tone of her letters darkened considerably, their main theme was the hopeless situation in which the Jews had found themselves. Ilse patiently explained to her distant friend how was life in a border town with many German inhabitants, describing the ethnic clashes during the crisis, the tragedy of Jewish refugees after Munich etc. Efforts for “leaving the country” came to be ever more significant subjects of her letters – indeed, the Webers had made several systematic attempts at emigrating, and invested considerable financial means, but all to no avail (to Ilse´s great despair). The only plan that eventually went off (even though several months had elapsed before the parents took the desperate step): at the end of May 1939 the little Hanušek left the country in one of “Winton´s trains” on his way to Britain to meet “Aunt Lilian”.

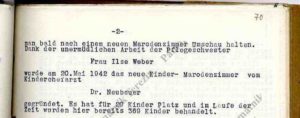

In this report is mentioned that due to the tireless work of Ilse Weber, who worked here as a carer, the children sickroom with 20 beds was established here in May 1942 and about 369 were treated in the course of time.

The situation of the Weber family was rapidly deteriorating: after the outbreak of the war life in Vítkovice proved to be impossible for the Jews. Her husband Willi found accommodation in Prague and as we learn – from Ilse´s letters to Lilian and later (when Lilian had entrusted Hanuš to the care of her mother in Sweden) to “aunt Gertrude” – about the troublesome life in Prague: Ilse got a job as a seamstress making shopping bags and swimming caps. But she devoted her free time, on Fridays and Saturdays, to her true passion – care for children. She would go to the children´s refuge run by the Jewish community, where – in Ilse´s own words – “her music playing made her virtually indispensable”…

Brief an Mein Kind, one of the most famous poems by Ilse Weber, Terezin Memorial, so called Heřman collection, PT 4109, © Zuzana Dvořáková.

In February 1942, Ilse, Willi and Tomík were deported to the Terezín Ghetto where – according to Willi´s testimony after the war – Ilse´s literary work reached its pinnacle. According to him, Ilse´s concerns and depressions gave way to active work – in Terezín, Ilse asserted herself as a nurse serving in children´s sick bay where (just as earlier in the Jewish refuge in Prague) she primarily played her guitar (smuggled into the Ghetto) to the children and rehearsed various performances. Moreover, after her “working-class” intermezzo in Prague, she got back to art: she began writing dozens of poems and songs, some heart-rending confessions and raw descriptions of the reality of the Ghetto, while her other works were designed to strengthen the hope of her fellow inmates. In the view of many Holocaust survivors who had known her, quite a number of those poems/songs became “folk melodies” and turned out to be ”the property of all the inmates” in the Ghetto.

Only several “neutral” letters from Ilse came to Sweden from Terezín, the last one in September 1944. Shortly afterwards, Willi left by transport to work allegedly somewhere near Dresden (such was the official explanation of the Terezín SS Command), while the real destination was the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Willi hoped that his departure would save the rest of his family from another transport. Yet, shortly after Willi had left Terezín, Ilse with Tomík volunteered for another transport. As a result, Ilse and her younger son fell victims of the last ”liquidation“ wave of transports from the Terezín Ghetto to Auschwitz. Still, her own life story and her literary heritage (buried in Terezín and dug up by Willi after the war) could not be silenced – this is the story of a loving and active life, of a sensitive and suffering woman, story of a devoted mother, and also of constant fighting for what is better in human nature, a story of scoring an inner victory…

Kl