One of the things that made Terezín stand out among the ghettoes of Europe was its rich cultural and spiritual activities. The SS commandants however never officially defined the cultural and spiritual life of Terezín by any order or decree. They took different stances on it in different periods, ranging from complete abolishment to times when it was tolerated and even used in Nazi propaganda for their own ends. The actual approach of the SS towards cultural life was cynical. The Nazis generally allowed it, knowing that certain death awaited the prisoners anyway, therefore they let them “have their fun”. On the other hand, the SS did not realize or know that any cultural activities were a natural form of resistance for the prisoners, a source of strength and hope, something that allowed them to forget the everyday misery. The Nazis frequently did not know what was the actual content hidden under the names of individual cultural events, they did not grasp their real meaning. This was the reason why the spiritual activities could blossom in such an unprecedented manner.

In fact, the spiritual life in Terezín was completely different to what the situation was in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia as such. Despite the fact that the Jews of the Protectorate were forbidden to take part in any cultural or spiritual activities, they could do so in Terezín. Hundreds of professional artists, scientists, college professors and tens of rabbis were deported to the ghetto. Complex works of art were not only performed here, they were even created, despite the harsh conditions. The extent and quality level of the cultural life in the ghetto was characterized by Ruth Bondyová who said that there were plays staged in Terezín that no one would ever dare to allow outside the ghetto. In a sense, it was the freest stage in the whole of the occupied Central Europe.

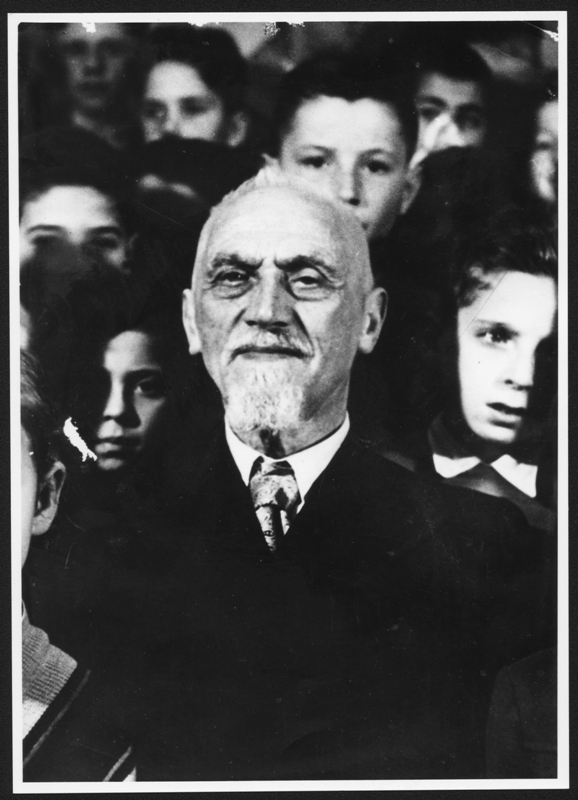

Very important for the mental well-being of the prisoners was participation in religious rites, services, rabbi lectures and celebrations of religious holidays. It gave the prisoners a semblance of normal life and a chance to forget the almost unbearable living conditions in the ghetto. One of the people present at a lecture of the ghetto’s de facto most prominent rabbi, Leo Baeck, remarked that “for a moment, it was the way it used to be.”

There was an interesting mixture of various communities in the ghetto, with many languages spoken. The Czech rabbi Richard Feder remembers that there was an interesting contrast between the Czech Jews, most of whom were assimilated patriots, and the group of Sephardi Jews from the Portuguese Jewish community in Amsterdam who began to arrive with the Dutch transports starting in the spring of 1943. Some of the Orthodox Jews in Terezín abstained from eating meat, pate or salami, even though they were starving. Feder recounts how people were given only 30 grams of meat per week, but the Orthodox Jews exchanged it for a piece of bread, as they did not want to violate the religious dietary laws. Later, a meat-free kitchen was set up for these prisoners.

There were not only Jews imprisoned in the Terezín ghetto, there were also Christians, baptised children from mixed marriages and converts. All of these celebrated various holidays in the ghetto. The SS headquarters for instance allowed for Passover to be celebrated in keeping with the ancient tradition. This meant that those who applied early enough were given matzo instead of bread. Another holiday that was celebrated was Hanukkah – the Festival of Lights, as were Christian Christmas. People managed to procure candles and even a Christmas tree for these holidays.

Once there were enough Protestants in the ghetto to form a community which asked the Jewish Council for permission to perform their own rites and services, the Elder Jewish Councillor Jakub Edelstein supported their request, saying: “There is after all only one God we love. It is of no consequence in what ways we shall worship Him.”

Do