“Agriculture” or Landwirtschaft was part of the Economic Department of the ghetto administration. Its beginnings were difficult because basically everything that is needed in agriculture was missing. At the same time, prisoners assigned to work here were mostly untrained and often came from the cities; some of them had never held a hoe or other tools in hands before. Due to the lack of experts, the daily from time to time published calls for beekeepers and veterinarians asking them to register, later followed by calls for grass cutters and tractor driver, etc.

The Department took over the first agricultural area as early as in mid-December 1941. Gradually it grew to hold up to 311 hectares, out of which over 70 ha of arable land, 84 ha of meadows, 73 ha of pastures, 15 ha of gardens, the rest being forest and others. 35 ha were leased by the Terezin Police Prison in the Small Fortress. Field economy was based on growing oats, poppy seeds, potatoes, corn, etc., while inmates working in vegetable gardens took care of cauliflowers, beans, carrots, parsley, leek, spinach, celery etc. Fruit trees were harvested for apples, pears, cherries and sour cherries, plums, apricots, and peaches.

The livestock production boomed as well. At the beginning of 1942, two pairs of draft horses were transported to Terezin. At the end of the war, in addition to about 30 horses, there were also ca. 70 pieces of cattle, more than 60 pigs, sheep, poultry (hens, geese, ducks, and turkeys), bee hives and silkworm farming.

Even young people aged 14 and more involved in agricultural work, mostly in so-called youth gardens. The diary of Pavel Weiner (born 1931) says: “Since I am assigned for work in the garden, I have to hurry not to be late. We start at half past seven. At that time we gather in L 410…. First to come is the division of duties. My work is to make pots … I am looking around to see what grows at which place so as to possibly taste it. I feel that I am working for the first time in my life today. At home, I would certainly not do it. ” (Diary, 4th May 1944). With great care it was possible to secretly take some cucumber, onion, apple, etc.: “l just took two carrots and an apple… in the 4th garden l bit in an onion and then planted it again. “ (Diary, 11th August 1944).

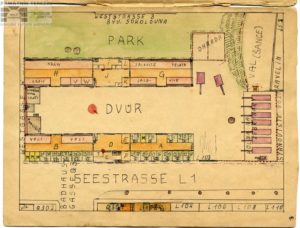

Another of the boys, fourteen-year-old Martin Robitschek (b. 1930) worked from October 1944 in the farmyard of the street L 1 – Seestrasse, where the cattle was stabled. He cleaned the stables of horses and oxen, and later he went with ox-wagon for hay or straw on the field. Martin made a map (see the picture), in which he drew the places of many animals and the distribution of facilities and equipment for agriculture and livestock care (e.g. the room for centrifuge and milk instruments, a chamber with veterinarian tools, etc.).

All yields from the farm were intended solely for the SS, the prisoners themselves gained nothing. Only in case that the vegetable failed to be exported in time and faded or was otherwise impaired, the SS members allowed its use in the prison kitchen. It was mostly the diet of children that was then enriched. The prisoners took no benefit of livestock either as the slaughtered meat was exported outside the camp. If meat appeared on prisoner’s menu, it was mostly horse meat coming from forced slaughters in the slaughterhouse nearby Terezin.

The Department of Agriculture provided jobs for hundreds of prisoners. Despite all the hardships and restrictions associated with working in the fields and gardens (e.g. the prohibition of taking vegetables and fruits – in case of getting caught guards were allowed to shoot at prisoners), this kind of work assignment had certain advantages. The prisoners got out to fresh air, beyond the walls of the ghetto. And if being careful, the yields provided supplement to their insufficient rations.

Se

- Norbert Troller: Zahradnictví v šancích pevnosti. PT 14157

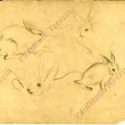

- Petr Kien: Skica králíka, PT 10114-5

- Petr Kien: Skica vepře, PT 10114-5

- Pracovní průkaz vězně ghetta Lea Kolínského, APT 7000_1

- Pracovní průkaz vězně ghetta Lea Kolínského, APT 7000_2