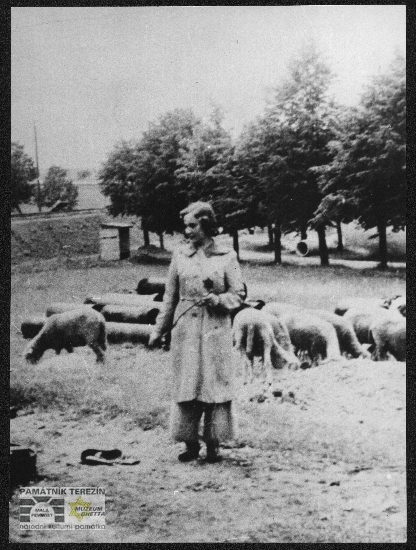

Doris with grazing sheep during her imprisonment in the Terezín Ghetto, 1943, Památník Terezín, FAPT, A 4423.

She was born in Jihlava on April 7, 1926, into the family of Karel and Růžena Schimmerling. In 1933 the family moved to Brno where father worked in a bank and later in an insurance company. Doris had a brother named Hanuš who was five years her senior. Both finished their elementary schooling in Brno, while her brother managed to pass his school-leaving examination in 1939. The family had to leave their original apartment in November 1941 and moved into a three-room apartment in Offermannova Street where other Jewish families had already occupied one room each. The family was then deported to Terezín by transport U on January 28, 1942. By that time, Terezín was still inhabited by its original civilian population and the Jewish inmates stayed in the town’s barracks. As Doris recollects, it was in the Schleuse (sluice, in fact a processing point for incoming or outgoing transports) where the family was separated: father and brother were sent on to the Sudeten Barracks, while brother soon afterwards lived in different houses where he also served as an educator. The two women were accommodated in the Hamburg Barracks. Later on, thanks to her labor deployments, Doris passed through a number of other dormitories – she lived in the so-called Western Barracks as well as in the much requested garrets where she stayed either with her friends or alone. Already in the Ghetto the family was grief-stricken when, soon after arrival, their grandmother died of pneumonia; as time went by, the mother began to suffer from health problems and she died after an operation in February 1944. Doris herself had no health complaints. True to say, she underwent hepatitis in the camp and suffered frostbites during the winter months due to incessant work in the open air. But as she herself says, her outdoor labor eventually toughened her and made her stronger.

Tending Lambs

From the very beginning of her stay in Terezín Doris was assigned to work in agriculture, initially in gardening, later working in the fields. But she spent most of the time as a shepherd girl (some of the former inmates have been calling her “the lamb“ to this day). A herd of sheep numbering 300 heads appeared there in the early summer of 1942. The assigned shepherd girls had to tend the sheep completely, i.e. feed, milk and shear them. During grazing each girl had to look after a heard of some 70 sheep. They even had a shepherd dog named Tiger to help them. Their working day started at seven in the morning and ended at five in the evening, followed by some free time. One of the girls always brought their food portions from the Ghetto to the pasture – but most of all – the girls looked forward to the bucket of food for the shepherd dog because its contents came from the SS kitchen and proved to be much tastier than food for prisoners. Doris used to take a book with her to the pasture, and in addition to tending the sheep she used her time for education and broadening her horizons – after all, she was imprisoned in Terezín at the age between 16 – 19 years; under different circumstances she would have been studying at a grammar school by that time. During her leisure time she would join her friends and make use of the offer of Terezín´s cultural life – operas, cabarets and concerts. In 1943 she also rehearsed for the performance of a fairytale story Princezna Pampeliška (Princess Dandelion), directed by Irena Dodalová. But in the end the performance did not materialize.

Shepherd Girls in Danger

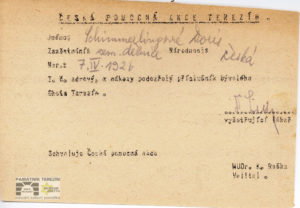

Doris Schimmerling´s registration card in the files of the Czech Help Action; she received the card after her liberation in the Terezín Ghetto in 1945, 1945, APT A 12735/Kartotéka.

Doris experienced a period of stress and uncertainty after October 7, 1942. At that time, a man appeared in the field behind Terezín, near the place where Doris, Eva M. and Hana S. were grazing their sheep. He came to help the Ghetto inmates by giving them food. It was Eva standing nearest the benefactor who took over his food parcel. During the evening return to the Ghetto, the gendarmes checking the inmates discovered the food “contraband” on Eva; she was detained and imprisoned in the Dresden Barracks. Doris and Hana were interrogated the following day. In the end, both shepherd girls escaped unpunished, since there was no evidence that they had actually spoken with the civilian or taken anything from him. As time went by, the fear of being assigned to a punitive transport disappeared as well, and the shepherd girls could get back to their work. Only Eva stayed in the jail for a whole month; still, she did not betray the civilian named Karel Košvanec. She maintained contact with the man until the end of the war and his food parcels helped many inmates survive in the Ghetto without persistent hunger.

Doris with her son Jan during their visit to the Urban family in 1963, private archive of Doris Grozdanovičová.

A picture of the sheep in Terezín has been preserved to this day. A photo of Doris with her herd of grazing sheep was secretly taken by a civilian foreman driller called Jaroslav Toman. He gave the picture to Doris only after the war and today it figures as an inseparable part of Terezín history.

What Happened Next?

Then came autumn of 1944 and Doris was left alone in Terezín, the only member of her family. Her father and brother Hanuš had been sent to the East with the last transports. Something quite surprising happened just before the camp’s liberation: a Czech gendarme named Josef Urban, who served in the camp at the end of the war, offered to adopt Doris. He and his wife would have liked to look after the deserted girl, especially when their own daughter had died three years earlier. In May 1945 the gendarme arranged a repatriation order for Doris to the town of Kostelec nad Orlicí, where she was supposed to live. But the adoption was never realized.

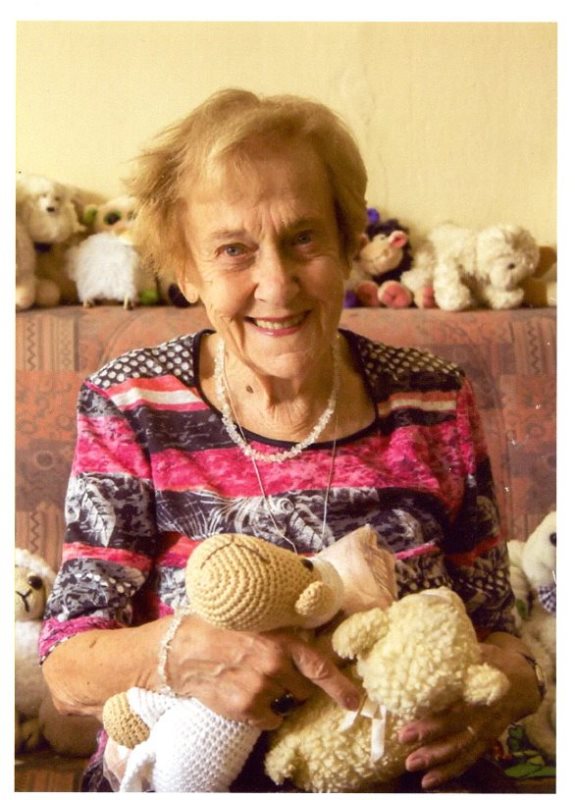

Doris at present with her own collection of sheep figurines, private archive of Doris Grozdanovičová.

When Doris´s brother had luckily returned from concentration camp, they were reunited and together went to Brno (their father perished in Auschwitz, mother died earlier in Terezín). Both Doris and Hanuš decided to study. Within one year Doris finished her grammar school, having made up for the three lost years, and passed her school-leaving examination in 1946. She then graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy (Arts) of the Masaryk University in English and philosophy, while Hanuš specialized in agriculture.

After her studies Doris began to work and live in Prague. In her job of an editor in the Československý spisovatel (Czechoslovak Writer) publishing house she made ample use of her good command of English and German, translating and acting as an interpreter.

Doris during a debate with Přerov grammar school students, January 2017, private archive of Přerov grammar school.

She has pursued these activities up to this day. She has a son Jan Grozdanovič from her marriage who is a lawyer working in the Czech Republic and England. The family comes complete with two grown-up grandsons. Doris still visits the relatives of gendarme Josef Urban, particularly during Christmas.

Doris lives a rich and varied life. She is an active member of the Terezín Initiative and an executive editor of its magazine. She frequently narrates her unforgettable experiences during debates with students at home and abroad. Encounters with Mrs. Doris are very impressive and unforgettable indeed.

Chl